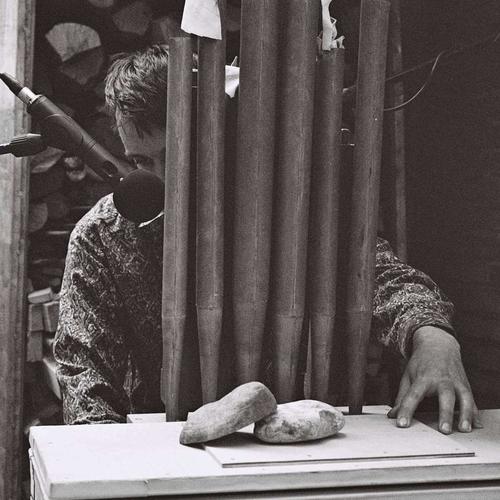

Tending the Instrument - Sholto Dobie in Conversation

Sholto Dobie creates instruments with analogue technologies which draw on the functions and designs of folk and traditional wind instruments, such as bagpipes and organs. For Dobie, their appearance several thousand years ago represent a technological shift in music, as humans extended the reach of their lungs, by creating bellows, bags and reservoirs that could sustain flutes and reeds more easily and for longer than human lungs. It is a drive that is echoed in more recent technological socio-musical shifts, such as electronic dance music. Dobie incorporates analogue electronics alongside handmade reed pipes, using basic prefabricated timer modules and industrial electric valves, to control air flow. Despite their apparent limitations, this simple set up belies a rich world of sonic and technological possibilities, and despite the functional origins of the technology, they can be reorganised, misused, giving them their own particular agency and voice.

Sholto Dobie was a tekhnē artist in residency in March 2024, during which this conversation took place.

Julia Eckhardt

Your project has a quite special take on technology and its historicity. Could you explain your perspective on this correlation?

Sholto Dobie

Technology, at it’s most basic, refers to the tools used to create something. It is also inseparable from social life, and political life. I quite enjoy thinking of the things we do, in these broad frameworks. Long before I began to work with bagpipe technologies, I was interested in the history of the instrument. I had grown up listening to bagpipe music in Scotland, the sound held a special fascination for me, but at some point I heard some bagpipe music from Turkey which unlocked a door in my listening, I heard these big ones from Italy and Serbia. As music and sound, it struck me as simultaneously very mechanical and paradoxically animal-like; from another world. It was kind of interesting to me, that something could hold those two things at the same time.

Technologically, I was interested in the bagpipe as shift from a breath instrument like a flute (which is very much tied to the voice) to an appendage, an additional lung, that permitted a continuous sound, without pauses for breath. There is some inherent mysteries in that shift, the drive for a long continuous music, for a voice which omits itself from another body, not a human one. Representing a de-centering of the musician, and a liberating of music from the corporeal realm. Bagpipes are thought to have appeared in ancient Greece, yet, the impulses are not very different from what currently exists in wider club or electronic music culture.

So yes, let's say I’m interested in technology and its historicity as a framework, for thinking about the world of sound, performance, and objects that I work with.

JE

You mention the anthropomorphic aspect of technology, how do you see this relation between instruments and the body?

SD

My work incorporates technologies from organs and bagpipes. In the case of these instruments there is a literal anthropomorphic element to their technologies. Their bellows and bags replicate the workings of lungs, the construction often required the use of animal skins, and their timbres were often intended to mimic human voices. The materials of my instruments have a more distant relation to the workings of a body; synthetic tubes and bags, manual gas valves, an air pump from a fish tank. Yet they do draw associations, in their autonomous inflating and deflating motions and the tangled network of tubes and valves.

However, in my work these instruments are not entirely self-playing or autonomous and the body is a necessary participant in their activating and performance. I do find the wider question of technology and the body quite interesting, in the context of the kind of things which I and others around me create. Where traditionally a technology should serve the body, I tend to gravitate towards instruments and objects that are awkward and clumsy to use, and that have some life of their own. In this sense performing the role of a caretaker and assistant, a role-reversal of the age-old mastery of technology/instrument. Sometimes I sing with the pipes or mimic their voices. Perhaps this situation, in performances, also gives the objects and sounds some mysterious agency, amplifying their personalities and bodily-ness.

JE

Could you elaborate on this aspect of bodily-ness and performativity a bit more and also link it to your role in maker/creator of the instruments? How do you go over the making, is it more ‘tinkering’, or more searching for specific results?

SD

I have moved through some different approaches towards constructing instruments. My initial performances used very immediate materials and were a long way from what one could call 'instrument making.' I used trash bags, air-mattress pumps, and second hand whistles and pipes of various kinds, smudged together with tape into temporary constructions which would rarely outlive the performance itself. Later, I became more interested in organ technology and spent several months making a functioning portative style organ, with keys, and a manual bellow. Currently, I have circled back towards assemblage, using basic, found materials, ready-mades that I forge together in simple ways.

I’m not much of a tinkerer. I tend to work by following some intuition, and quickly putting things together, which more often than not leads to some kind of failure, which in itself becomes a generative place to work from. Over time I’ve learned to become a little more trusting of those failures, the unintended noises, leakages, the workings of the things itself. I suppose all of this comes from wanting to let the 'instruments' and sounds speak for themselves, not trying to conceal anything or have them conform to some expected results.

Thinking about the relationship between making and performing, I don’t strive to have the instruments work dynamically with my body. There are countless technological modifications, which could be made, to make it easier to control and manipulate the results of the materials I work with, but that would change everything. Their industrial components, valves and timers, demand a certain choreography, care, and awareness that often feels less like 'playing' the instrument and more like 'activating' or 'organizing' the instrument.

JE

Relating again to the question of building/constructing instruments, and the context of the tekhnē project, could you elaborate a little more about the importance of intuition and failure? You mention those as being important constituents to your work, yet many people would not associate them to a general idea about technology, as the use of tools for control.

SD

In my current work, I am not interested in using technology to control, but more in the potential of misusing basic technologies, to reveal something particular. For example, recently I wanted to find some means to automatically control the flow of air. I purchased some solenoid valves (magnetic valves used for gas or water) and decided to control these in the simplest way possible with adjustable on-off timer modules. The valves worked, sounding the pipes, but they also made a very loud clicking sound. At first, this was undesirable, but over time, I started to find the sound interesting in its own right. When set to a fast on-off times, these clicks created a complex mass of tiny overlapping rhythms, like a chorus of insects which became more interesting to me than their original intended role.

I’m interested in unexpected encounters, spontaneity, mistakes, humour, clunkiness, awkwardness, gentleness, subtleties and all these might be pretty much antithetical to a general idea about technology and it’s associations with advancement and control. But of course, that is partly where my interest lies in recontexualising these materials and technologies. There is potential to transform or destablise their given roles, maybe to sometimes enchant them.

JE

The fact that you use electricity to activate the instruments has also an effect on the performance, and gives some sort of autonomy to the whole installation. Do you feel a distancing from them, or is that wanted?

SD

I wouldn’t say I feel a distance from them. I’m still quite intimately involved in activating them. I am quite interested in the tricky shifts that can occur in performance situations, and so the fact that they are somewhat autonomous, allows me to become a performer and a listener and an audience member all at once. I also think that this dynamic tends to decentre the performance, as the focus shifts between the objects, the performer, and the room. When there is no single focus point, the people who have come to listen need to negotiate the space themselves, and locate themselves within the performance—an engaged rather than a passive listening.

JE

I got curious about how your interest about the organ/bagpipes technology was awakened by listening to a familiar technology, but in an other cultural context. How do you think does memory shape the technologies that make the music through the times?

SD

I guess the question of technology and cultural/musical memory is a big one, and I haven’t really considered it in much depth. When I think about organs, or early electronic instruments, they went to considerable lengths to mimic and reference voices, horns, and familiar acoustic instrumentation, to evoke a kind of familiar language of listening, not to leap into the dark. But it seems to me our responses to sound are made up out of a messy web of personal/cultural memories, physical memories, and bodily responses that extend far beyond our individual lifespan. Surely, technologies that make music also speak to those different responses. I hadn’t really thought of what I do from the perspective of cultural memory. Sometimes people tell me what I do sounds Scottish, or this and that, but it’s certainly not a conscious decision of mine to evoke bonny highland memories. That said, my intuitions lead me to certain sounds and relationships between sounds, that are very personal and yet also part of some matrix of cultural bodily memories and projections, I am in a drift with my time and place.

Bio

Sholto Dobie is an artist and organizer working with sound in its broadest sense. He regularly performs in events, using loose structures, site specific methodologies and an array of sound sources including home-made organs and bagpipes. He has explored ideas related to folklore, environment a sonic phenomenon.

https://soundcloud.com/sholtodobie