Electro(nic) Mobilities: interview with three artist groups who design autonomous sound devices

In 1957, the Japanese company Sony launched the TR-63, the first “pocketable” transistor radio: a portable device with a 9-volt dry cell battery, measuring 11.2 cm long and 7.1 cm wide. The power cord was snipped. For the first time, listeners were free take their music with them, instead of being stuck listening to the family radio in the living room. The portable radio represented a form of independence and emancipation for young people. It were the early days of music on the go, which would become mainstream with the 1979 launch of the Sony Walkman®, since supplanted by today’s ubiquitous smartphones and Bluetooth earbuds.

Sony reached another milestone in 1991 when it brought to market the first lithium-ion batteries for camcorders, and later for cell phones. These lightweight, rechargeable batteries grew widespread with the advent of laptops and smartphones, playing an integral role in the miniaturization of our devices. Today, they are mainly used in “soft” mobility options such as electric bikes and scooters, as well as to power electric cars, which are expected to gradually replace internal combustion engines that run on fossil fuels.

The lithium battery has also spurred the development of mobile sound projects by improving portability, as described in this series of interviews with artists and collectives exploring the possibilities of movement. Following the battery’s trajectory from an abandoned bike on the streets of Paris to its reactivation in new systems, we cross paths with artistic practices grappling with the question of scavenging; advocating tinkering and DIY; pooling and sharing experiences; and building an independent knowledge base on mobile sound systems used underground or in open fields where power cables can’t reach. These “off-the-grid” artists are stepping outside engineer-designed technical environments by imagining and making devices tailored to their own needs. Their group listening systems offer an alternative to the personal sound bubbles created by Bluetooth earbuds, and to the privatization of public spaces. They are creating a different form of soft electro-mobility, without turning a blind eye to the environmental paradoxes that entails. Indispensable for manufacturing batteries – and, by extension, mobile listening practices – lithium is often presented as the “white gold” that will replace “black gold” on the road to an electric, low-carbon future. Yet extracting the metal from open-pit mines in Australia or salt flats on the Andean Plateau has dire consequences for the environment. To this day, the lightest of metals is almost never recycled. Artists are salvaging batteries no longer in use and putting them back into circulation, while also thinking critically about their own use of materials.

1. Interview with a Parisian cataphile collective

Beneath Paris lie the catacombs, an underground network of passages built for ancient quarries, which spans nearly three hundred kilometers and winds more than twenty meters below the surface. Officially off-limits to visitors, it's a labyrinth hidden from view, with no electricity, telephone network or GPS, which is home to many clandestine artistic experiments. Below is a conversation with a “cataphile” collective of underground party organizers who prefer to remain anonymous.

What impact have lithium batteries had on underground practices?

There's no electricity in the catacombs. We used to power the music nights, which are illegal by definition, by running kilometers of cables plugged into either streetlights or construction sites. At the risk of being caught out...

When lithium batteries began to appear and become more widely available, it really changed life below the surface. People had been using lead-acid batteries, the most common and cheapest, but they were very heavy and their performance wasn't great. That all changed in 2018, when free-floating scooters and bikes invaded Paris in anarchic fashion. They littered the streets, often ending up in the Seine or picked up by garbage trucks. It was an unbelievable mess. The lifespan of a scooter was 28 days on the street. Some had been smashed up during the Yellow Vests1 protests, others used as barricades. It was all going to landfill, and there wasn't really any recycling process. So we started to recover the vehicles. We also went to the river police brigade, who fish bikes out of the Seine, to scavenge spare parts like connectors.

How did you go about it? Handling lithium batteries can be dangerous.

Either we added another BMS2 to bypass the protections, or we stripped it and recovered the 18650s that were still functional. 18650s are the basic cylindrical cells assembled to form the battery. The name comes from their dimensions: 18 mm in diameter and 65 mm in length. They're a bit tricky both to take apart and to assemble, because they're soldered point to point using zinc. But nothing has caught fire so far.

We also use the 18650s in our headlamps. You can carry several in your pocket without it being too heavy. In terms of kilowatt hours per gram, they’re unbeatable. Long gone are the days of old-fashioned carbide lamps! 3 Free energy suddenly became available in abundance, everywhere in Paris. The entrances to the catacombs became a sort of Bermuda Triangle for electric scooters, which disappeared in droves.

What were the batteries used for?

We like to work with scavenged materials and make low-tech objects like this lamp put together with LED ribbon and technical tubing, which can be plugged into these little batteries compatible with everything, since they're 12-volt, the standard for most electronic devices. To power a musical parade float during the pension reform protests, we made a charging station from three damaged electric bicycle batteries. It's the slightly “home-cooked” equivalent of the lithium-based 220-volt power stations on the market, which cost a fortune.

In the catacombs, there's a long tradition of cataphiles building makeshift radio tuners known as “catapostes,” because back then there wasn’t anything very able or portable in terms of sound and weight. That tradition has been on the wane since the arrival of Bluetooth speakers, which are cheap and capable of blasting pretty loud. People who go down into the catacombs play music all the time. They used to use cassette players with alkaline batteries, which didn't last as long and cost a lot more.

We also built a float for festivals, a beefed-up version with sound, light, smoke, and flames! We built a rack with the equivalent of twenty bike batteries. It weighed 70 kg, and kept on running for over three days without us ever draining it. That allows for limitless creativity, with added mobility. We really witnessed lithium in all its power!

2. Interview with le laboratoire souterrain

Le laboratoire souterrain – the underground laboratory – is a duo formed by artists Sonia Saroya and Edouard Sufrin, who organize unconventional events both under and above ground. They also create portable sound systems specifically designed for walking. http://lelaboratoiresouterrain.com

How did you come up with the idea to organize sound walks underground?

In 2013, we started organizing exhibitions of installations and concerts underground in Paris.4 Beneath the cobblestones, you feel like a deep-sea diver – pretty vulnerable, because your power supply hangs by a wire connected to a utility pole above ground. You run the risk of being disconnected by the authorities, and we have experienced a few mishaps. That’s what led us to develop a completely standalone concept.

So we embarked on a series of underground sound walks,5 which are easier to organize. We invite an artist to create an hour of sound to be played during a nighttime walk in subterranean passages.

What’s the concept behind the experience?

It’s really the idea of carrying sound, listening on the move, sound that moves and becomes warped in the tunnels. It’s an hourlong walk that’s quite hypnotic, a group sound experience in a place unfamiliar to many. The physical experience of setting your body in motion and exerting yourself puts you in a special frame of mind for listening. Underground is an immersive place by definition, with its own acoustic qualities, the resonance of sound in the passages, the micro-noises, the physical and emotional sensations. It creates an intensity that's not so easy to match in other settings. It's also one of the rare spaces of complete freedom. It's an opportunity for the guest artist to rewrite the rules, to explore new terrain together, to step out of their comfort zone.

The underground passages are narrow and damp in places. What kind of equipment do you use?

We carry all our gear on our backs, which means we have to pack light. When we do these underground walks as a group, we try to have one sound system for every ten walkers. The sound is quickly absorbed by bodies in the narrow tunnels and bends. That also places a limit on the number of participants, to ensure quality listening. The maximum is about fifty people. In the early days, we used jobsite speakers powered by drill batteries. They’re very rugged, with metal cages – tools made to be used and abused, which can take a beating and have about ten hours of battery life. But they’re a bit expensive: between 150 and 200 euros, plus the cost of the battery and the charger. And very heavy!

We wore them across the chest, with a strap that dug into our shoulder, which wasn't very comfortable. But the sound quality was decent, albeit lacking in bass and volume. We tested a lot of equipment, but couldn't find what we were looking for in shops.

That's when we met Antoine Capet from Brut Pop,6 who’s also a fan of underground and portable sound systems. Together we started tinkering with old Hi-Fi speakers from the '80s, often decent equipment that had been thrown out in the ritzier neighborhoods of Paris. We reinforced the corners, added small amps, and built homemade battery racks. A friend of Antoine's who belonged to an association that disassembled old scooter batteries salvaged cells that were still functional and re-soldered them.

We were pretty wary of those DIY lithium batteries. We move through confined spaces wearing them on our back – the perfect recipe for real trouble in the event of a fire or explosion. We wanted to avoid those kinds of risks. You can find inexpensive technical solutions by repurposing amps bought for under ten euros on the Internet, or things found in the street. But we were very particular about the sound quality. We wanted to build our own speakers from scratch.

Being artists, how did you go about building your own audio equipment?

We’re not engineers, so we learned on the fly. We tried to understand what physically takes place inside a speaker. We partnered with Jérôme Fino, a video artist who had also experimented with turning salvaged speakers in an audio backpack, for Les Concerts Dispersés,8 but they were very heavy and physically taxing to carry.

Together, we obtained a grant to develop this “work-tool” called Bruit de Fond,8 which is designed to be a system for experimenting with music in movement, and in situ sound installations. We crafted speakers tailored to this form of ambling sound practice. Everything was done by hand, from the carpentry to the custom waterproof fabric bag, along with the electronics work and configuration.

We ended up building five speakers, each weighing around 8 kg, which enabled us to gain in power, quality and spectral width. The battery is made up of 5 lithium-ion cells from electronic cigarettes, which last between 6 and 30 hours depending on the volume and type of sound. The project has brought together artists from various fields (music, visual arts, theater and dance), who have helped us develop a tool that will be useful to an entire community of people experimenting with unconventional approaches. For us, it's important to make this knowledge accessible so that everyone can adapt it to develop their own project. It also explores the question of autonomy.

So the speaker systems are reliant on lithium batteries…

Lithium batteries have made these systems lighter and paved the way for new approaches to sound that trade concert venues for the great outdoors. However, the issue of environmental conditions has yet to be resolved. That’s the case for the mining of metals needed to make the batteries, and more broadly for all electronic equipment ordered from China, which involves natural resources, water, labor and transport. All this equipment has facilitated DIY for musical and sound practices, but has also played a part in damaging the environment, albeit on a smaller scale. That’s the blind spot of these tinkering practices. That said, if you compare them with the human, fossil, and electrical energy needed for a concert venue with a capacity of 500 to 5,000, plus all the equipment and cables that entails, we’re not doing too bad in terms of our carbon footprint per person!

3. Interview with Pierre Pierre Pierre and Antoine Capet

Pierre Pierre Pierre describes himself as “a self-taught artist interested in dysfunctional materials and situations” who takes a keen interest in handmade electronic instruments and home stereo equipment. Antoine Capet is a musician and special needs teacher, and co-founder of the BrutPop collective. Together with composer, sound artist and musician Lucie Bortot-Schneider, they have developed the OctoPloc,9 a mobile sound system with eight speakers that can be linked for spatialized listening, which was created with help from Zach Poff and Stephan Voglsinger.

What was the genesis of this project to create a portable sound diffusion and spatialization system?

It emerged from a European cooperation project. The Nantes-based experimental cinema association MIRE10 brought together artists for a Wandering Sound & Images seminar on traveling, expanded cinema. The project was inspired by the Noise Bombing events in Indonesia11 and is a response to the difficulty of finding urban spaces to organize open, spontaneous events. The European project enabled us to develop tools for performance practices with film projectors, so that we would no longer have to deal with old projectors breaking down, shortages of spare parts, or the soaring prices of rare and “vintage” items. The idea was to be independent and to take advantage of new technologies.

At MIRE, the initial idea was to make the equipment light and self-powered, so that we could take it with us on a walk beyond the lighted parts of the city, find a place for projection, and play the sound from a film or have musicians perform live.

What led you to build the OctoPloc?

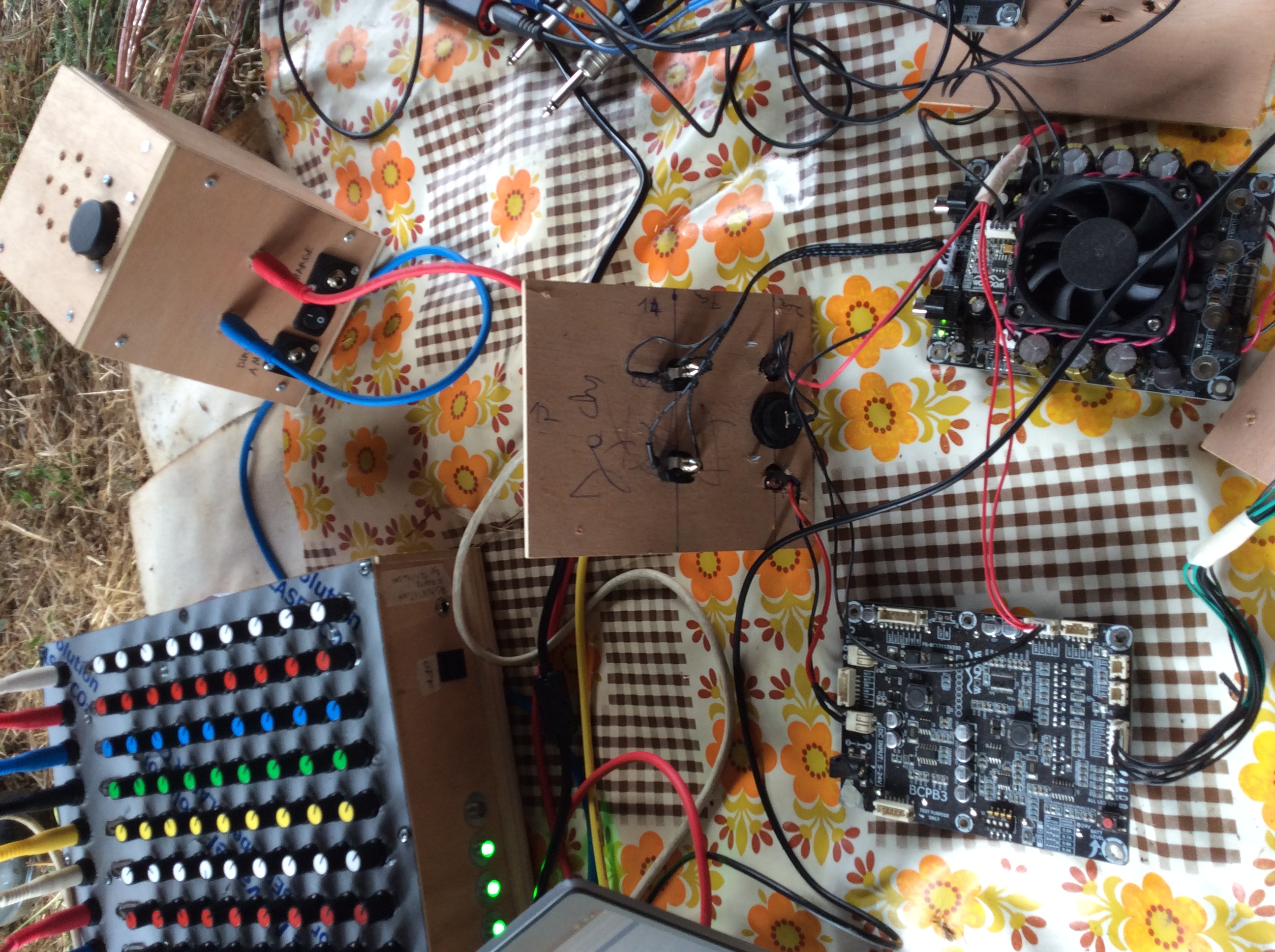

We wanted to create a custom system, or DIY rather, that could be reproduced and adjusted as needed. We developed a set of eight speakers, transportable in four backpacks, so that we could create spatialized music and bring the speakers closer to the audience. And to avoid having to generate too much power, so that we would save energy and be more discreet, both key whether in the city or in a “natural” area. As the budget was very tight, we chose passive speakers that were common enough to be found easily on the secondhand market. Then we built amplifier boxes using lithium-ion cells scavenged from scooters. To send sound to the eight amplifiers, we built a mixer with eight inputs and eight outputs, which is also battery-powered. We opted not to go digital, as it didn't seem necessary and we wanted to learn about audio electronics, so it's 100% analog. We also wanted to avoid ordering from Amazon.

For us, it was a lot more important to build and put together things as much as possible, while being fully aware of how ridiculous the situation was at times – we don’t have the resources or expertise of JBL! We’re still amateurs. When you turn it on, it makes a “ploc" sound. That’s why we called it the OctoPloc!

What's your opinion on the rise of lithium batteries and their impact on sound practices, particularly in terms of mobility?

Lithium batteries make a lot of things easier and new things possible, but they also limit projects, or at least put guiderails on them. If I learned the flute instead of electronics, I could also make mobile music, without Amazon or lithium.

During the course of the project, we met a member of the Ciné-Cyclo association, which organizes open-air film screenings with electricity generated by the pedal power of bicycles. Their motto is, “no battery, no storage”! They generate electricity when they need it, and that's it. With supercapacitors to store it for just a few seconds – the time it takes to change riders.

Translated by Ethan Footlik

Bio

Marie Lechner is a teacher, author, and curator. Formerly a journalist at Libération, she oversaw artistic programs at La Gaîté Lyrique in Paris. She has co-curated several exhibitions at venues such as La Gaîté Lyrique (Paris), HMKV (Dortmund), MU (Eindhoven), the Biennale Internationale du Design (Saint-Étienne), and NRW Forum (Düsseldorf). Her latest exhibition, House of Mirrors: AI as Phantasm, was held at HMKV (Dortmund). Marie teaches at the École Supérieure d'Art et de Design d'Orléans and the École Nationale des Arts Décoratifs in Paris. She is currently leading Lithia, a research-creation project examining the challenges of lithium extraction in Alsace.

-

The Gilets jaunes or Yellow Vests movement – named after the yellow high-visibility vests worn by demonstrators – is a spontaneous protest movement that appeared in France in October 2018, initially on social networks, in response to rising gasoline prices. ↩

-

Battery management system, which is used to monitor the various components of the battery. ↩

-

Acetylene gas or carbide lamps are portable lamps whose light source is a flame produced by burning acetylene gas. ↩

-

Nuit Noire http://lelaboratoiresouterrain.com/nn.html ↩

-

Initiated by special needs teacher Antoine Capet and musician David Lemoine, the BrutPop collective has been working since 2009 on access to music practices for an audience that is predominantly autistic or mentally disabled, via sound workshops, DIY string instruments, and exhibitions. https://brutpop.com ↩

-

Les Concerts Dispersés, initiated in 2017 by the artists Jérôme Fino, Yann Leguay and Arnaud Rivière, is a rural concert series that trades concert halls for various places spread across the Lot valley, which have particular acoustic and visual qualities. http://concerts-disperses.org/ ↩

-

Bruit de Fond received a grant from the Dicream program offered by the French National Centre of Cinema. https://soniasaroya.com/dehors.html ↩↩

-

https://www.filmlabs.org/wiki/fr/meetings_projects/spectral/wanderingsound system/start ↩

-

Jogja Noise Bombing (JNB) is a community of noise artists who appear unexpectedly in public spaces and put on illegal concerts (to compensate for the lack of concert venues) powered by the city’s public grid. ↩