Extreme Traditions: On Bandung’s Intergenerational Sonic Ecologies

After a long ride on my motorbike, I arrive in Ujungberung from Bandung; it's one AM, April 2023 and we’re fully into Ramadan. I have come to watch the traditional trance ceremonial réak, (the Bandung sub regional variant of the popular "horse trance dances" present throughout and outside Indonesia), during which a trance master coordinates a series of spirit possessions with the musical accompaniment of an ensemble of percussion and shawm. But this time is different. Tonight, the troupe Balebat Pakidulan will play sasahuran: a practice occurring during the holy month where performers execute different styles of music to create early morning noise and wake people for the first prayer and meal of the day before the fast starts. Everyone is preparing, stoked for the night to come. A musician says: "It’s going to be very noisy and fun! Since during Ramadan it is forbidden to play proper musical events, this is our way to use the sahur as a little social demonstration!"

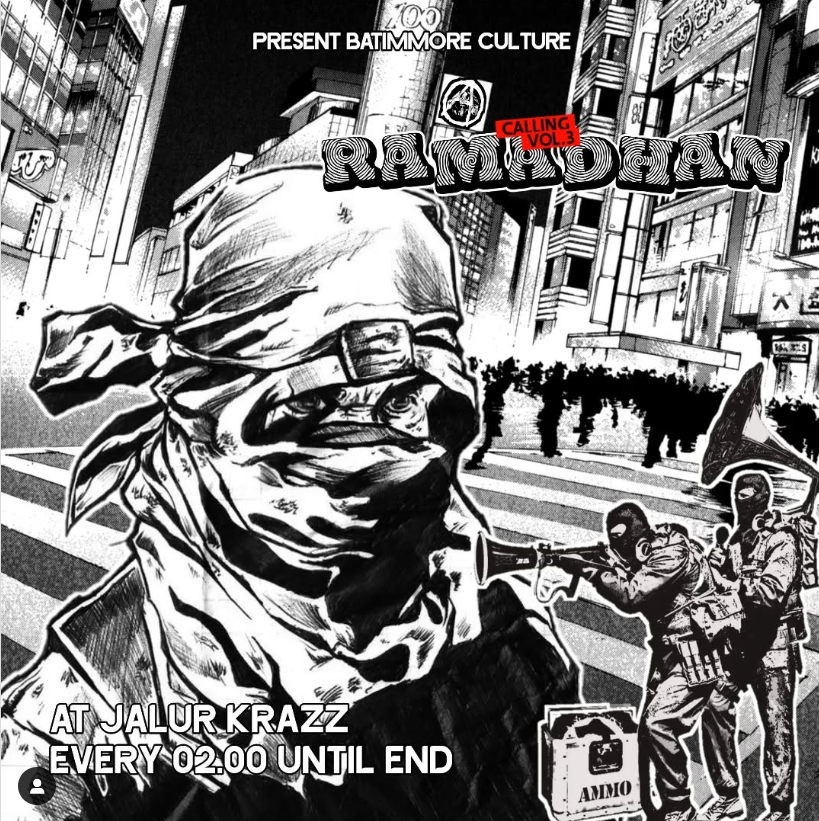

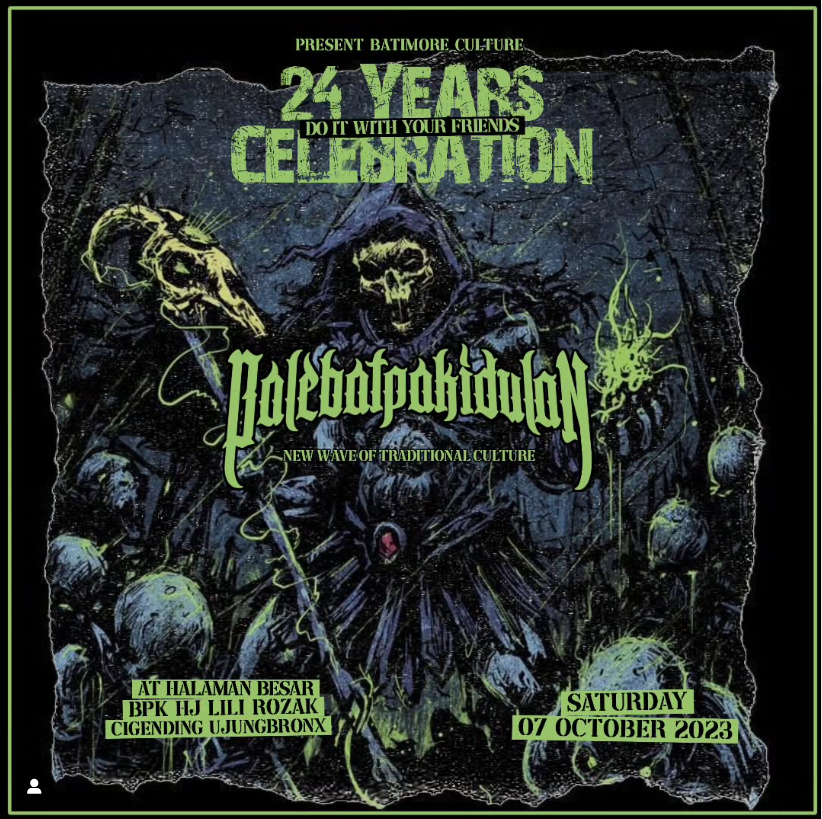

The event was advertised on social networks with a flyer more reminiscent of a punk event than a religious parade. In the illustration, a collage of different comics foregrounds someone with a balaclava and two figures in military attire brandishing audio-weapons. The background is an anonymous metropolitan centre swarming with people and an anarchist symbol looming from one of the buildings. The flyer includes the event location, Jalur Krazz, a play on the word keras (coarse/raw), referring to the street going from Balebat Pakidulan’s headquarters in the sub-district of Cigending to the city’s traditional market, jalan Nagrog. The event is organised by Batimmore Culture, a youth collective from the city of Bandung’s peripheries organising traditional and contemporary music events, of which Balebat is a part. Named after a crasis of the words "Bandung Timur" (east Bandung) the collective’s name is also a wordplay on Baltimore, in the same way that Bandung’s Ujungberung district becomes Ujunbronx, likening the underground and gang music imagery of East Coast US rappers with the Bandung District. The markers and signifiers of underground and oppositional subcultures—anarchist symbols, punk imagery, hip-hop geographies—are invigoratingly off-kilter for a religious and traditional performance. One of their big banners says: "New Wave of Traditional Culture," with a design that was clearly inspired by metal aesthetics and its focus on the otherworldly and the undead.

|

|

|

|---|---|---|

Left: Sasahuran Réak anniversary flyer, © Balebat Pakidulan

Middle: Balebat Pakidulan’s anniversary flyer, © Balebat Pakidulan

Right: The reak troupe Balebat Pakidulan, © Majapride Photography

Around two AM we gather in the streets for the event. The troupe’s portable PA is carried from their headquarters to the main road. They start, breaking the night’s silence. The lively interlocking rhythms of the dogdog réak percussion vibrate in space, accompanied by the amplified, piercing sound of the tarompet double reed instrument and singer’s vocals. The singer starts shouting in the microphone: "Sahuuuur, Sahuuuuuur! Wake up and pray! Sahuuur!" The Balebat troupe begins marching from the small, labyrinthine alleys to the main road. In a few minutes, the anonymous, deserted streets fill with young boys and girls observing and dancing with all the performing groups. There must be around 3000 people. The youth occupy the street yelling at each other, ululating, clapping their hands and throwing firecrackers every other minute, saturating the intense collective soundscape with individual effervescence and sonic power.

The sound is almost unbearable. The overpowered PAs’ volumes are very aggressive, coming from all directions, while the whole place fills with the coloured haze of smoke bombs. Sound is coming from everywhere. People jump on each other’s backs swaying banners celebrating the community: "Care for your loved ones, be good to people" and "Stop the arrogance in our community." Punks, metalheads, hooligans, boys, and girls dance and jump, mixing traditional dance moves with punk stunts, throwing each other around in the air, screaming and laughing. Human sounds and noises surround me, blending with the flow of cars and motorbikes passing through the clogged parade. The energy is palpable. Everyone is clearly happy and proud of this place. After an hour of participation, Kinoy, friend and singer of the famous second generation Ujungberung death metal band Undergod, which since a long time has invited réak troupes to open their shows, appears. From the middle of this chaos, he runs towards me shouting: "This is Ujungberung! Have you ever seen anything like this?!" Laughing, raising my voice to be heard, I answer that, no, there is nothing like this anywhere else.

A Sasahuran réak event in Ujungberung, Bandung

In this anecdote I tried to illustrate the point that the aesthetics and politics of the Bandung underground, especially punk and metal scenes, have expanded, bridging sonic cosmopolitan subcultures with traditional music. Far from being unrelated, polar opposite phenomena, ethnolocal traditions and cosmopolitan movements participate in a multi-generational and inter-genre collaboration of youth from different walks of life, united by the importance of resisting cooptation by neoliberal agendas through informal politics. But how did metalheads end up being allies to traditional musicians? How did this specific trance performance adopt the political stance and performativity of loud underground music? How did all of this evolve from transnational cosmopolitanism to a focus on Sundanese ethnicity1 and its music?

Beyond Underground: Loud Popular Music in Indonesia (1945-1980)

Indonesia’s encounter with loud popular music is somewhat coeval with its independence from Dutch colonial rule in 1945. First president Sukarno (1959–66) immediately limited national access to Western popular cultural artefacts, believing that music like rock ’n’ roll could pollute the youth’s national identity with new forms of moral degradation. The idea was that the performance of Western repertoires was a kind of masquerade which obscured an authentic, local self. Western music was criminalised as an enemy of tradition: music artifacts were seized by police, radio and public airings were forbidden, and artists playing these music genres were imprisoned, charged with political subversion, and subjected to lengthy sessions of interrogation and re-education. For instance, Elvis Presley records were publicly burned, and in 1965, a popular Indonesian rock ’n’ roll band, Koes Plus, was arrested for playing The Beatles. Sukarno’s prohibitions did not, however, prevent young people from consuming Western rock music, which became a symbol of youth opposition against state authoritarianism. The Indonesian 1960’s rock music scene flourished with the establishment of a large variety of rock bands.

Yet, in the aftermath of the 1965–66 genocide violently perpetrated by the Indonesian army against the "enemies of the state"—from communists to Chinese-descendants, peasants and the like—the cultural landscape changed dramatically. In contrast to his predecessor who was forced to resign, General Suharto’s rule enforced a free-market oriented pro-Western government, becoming infamous for its widespread corruption and brutal suppression of opposition. Suharto’s regime allowed the penetration of emergent consumer cultures through the allures of the American middle-class lifestyle, of which Western music was a particular form apt to exert its soft power. But while during the 1970s and 1980s official channels such as television, print, and radio were vehicles of propaganda circulating tame and vapid love songs in allegiance with the government, home taping technology signaled the beginning of a period of disintermediation from the government through the penetration of underground music. International punk and metal scenes were used to being left out of mainstream circulation, establishing alternative circuits thriving on international bootleg and distribution networks. Young Indonesians took advantage of this control gap and used the transnational underground as a source of political strategy, reworking their place in society and articulating their discontent. Unbeknownst to governmental control, commercial capitalist audio technologies had made neoliberal consumerism a weapon against itself.

Indeed, notwithstanding the state’s attempts at instilling conformity, major student demonstrations erupted during the 1970s in universities throughout Indonesia. While music, whether traditional or alternative, could be co-opted, youth dissatisfaction could not. On the back of this discontent, throughout the 1980s and 1990s, pressure from ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations), the World Bank, and the international financial community pushed Indonesia significantly closer to the free market, while the archipelago, along with the rest of Asia was about to face its biggest monetary crisis in the late 1990s. Such economic depression fostered a further collapse of class divide in independent music communities, bringing together a dispossessed working class with a middle-class that had seen its progressively accumulated wealth now taken away. Amidst this socio-economic scenario, ethnomusicologist Jeremy Wallach noted that for many young people participating in the protests, underground music was among the main cultural forces galvanising Suharto’s fall. Not only was the underground the only alternative to bland, boring nationally-controlled music selections, but it also became one of the major alternatives and exceptions to the regime’s consumer model: a mesh of politically engaged social practices and aggressive musical genres.

Based on statements by scene participants in zines and alternative publications of the time, like Rottrevore Mag and Revograms, in Indonesia the underground was perceived by music fans as a group of transnational youth-oriented genres distinguished by a fundamental aesthetic: keras (hard/loud), namely punk, metal, and hardcore. Aesthetics and genres aside, the underground was, like anywhere else worldwide, distinguished by its veneration of social pillars like community, rejection of established powers, and an independent lifestyle. This is clear in statements by underground musicians that appeared in a Rottrevore Mag issue in the early 2000s:

"Some undergrounders, with the motto 'Anarchy, Equality, Peace and Freedom', try to liberate their way of thinking and be liberated in expression or behaviour. Many behaviours are born from this idea, displayed radically. One way is through music. 'Underground is not music. Underground is more of an attitude statement. Music is only part of that,' said a follower of black metal. [...] Alwin, from the same school, also added that the underground is a rebellion movement against the establishment. [...] 'All music genres can be categorised as underground if the genre or band adheres to underground methods,' explained Rio, guitarist from the brutal death metal group, Bloody Gore. 'Genres like death metal/grindcore will always be underground because this genre is not mainstream and is difficult for people who have never heard of metal before to get it. Of course, this is also accompanied by the attitude of the band itself.'"

The Indonesian underground was fundamentally a political stance enabled by music. Being underground meant rejecting the music industry’s product-oriented system while following an anarchist, egalitarian stance and a DIY pragmatism; strategies leading to radical freedom of expression and independence in a time of high interdependence and heavy restrictions. Interestingly, despite the focus on politics and practice, the quote’s last section implies inherent relationships between extreme music genres and the movement. Metal, punk, and grindcore are underground because they are hard to like. Their sound is especially keras: coarse and uncomfortable. As Addy Gembel, singer and founder of death metal pioneers Forgotten, has stated in the book, Memoirs Against Forgetting : "Musicians preferred to identify themselves as underground. Their community is very proud of that designation, considering that not everyone likes music whose sound power is far above 60dB or far above the limit of human hearing tolerance."

Of course, the genre’s sensory overdrive was irrelevant if musicians defused the underground’s political power. This is evident in how participants described underground music as "politically unsafe." Such politics indeed were unsafe because they included (a) circulating censored and forbidden ideas—especially books—both physically among people in the circuit and in the musics’ lyrical content, (b) building small international trading and marketing platforms for cultural products that defied state control, and (c) creating social spaces for discussion and knowledge transfer where people could debate taboo topics. Indeed, Bandung’s underground ethos was founded upon social protest lyrics of bands like Minor Threat and Rage Against the Machine alongside works of philosophers like Nietzsche and Marx. It is no understatement that, after the 1965–66 'anti-communist purge,' literature linked to Communism by the Suharto regime was dangerous at best. As Addy has reported: "It was heavy. If you read Marx, it was like consuming cocaine! It was forbidden."

In fact, such texts were made available illegally thanks to translations made by university students, which were then circulated among insiders’ circles. If music alone can hardly change the world, certainly the Bandung case proves that it animates social circles in which upheaval and rebellion are nurtured and unleashed. Of all the telluric forces that this new cosmopolitan movement generated, the most widespread was the sonic assault of extreme metal.

Geotraumatic Sonic Ecologies: The Rise of Extreme Metal (1980-2000)

In Bandung it is almost impossible to be oblivious to the popularity of the underground. Roaming the streets, one can’t dodge citizens—old men and children included—wearing metal and punk t-shirts. This proves the strong circulation of underground music as a refraction of the wider interest that Indonesia has developed for more extreme sounds since the 1980s, when the first tapes by Sepultura, Morbid Angel, and Bulldozer managed to reach West Java’s music aficionados; a phenomenon that, considering how former president Joko Widodo had used metal attire as part of his promotional campaigns, has become mainstream in the long run.

When it comes to extreme metal since the 1980s, Bandung’s Ujungberung district has spawned the most influential Indonesian metal scene, which some argue might have been the biggest in the world by sheer numbers: The Ujungberung Rebels. With bands inspired by brutal death, slam, and grindcore such as Jasad, Burgerkill, or Disinfected and Forgotten, this peripheral context of urban marginality was fundamental for metalheads to build their sonic critiques of nation and the world by witnessing a centre-periphery disparity made evident by second president Suharto’s authoritarian neoliberal politics. If on a national level the regime allowed the penetration of emergent consumer cultures, Indonesia’s peri urban agrarian areas suffered a cold-blooded, extractivist industrialisation.

In places like Ujungberung, dwellers living on once-agrarian lands transformed into industrial wastelands experienced progressive marginalisation and alienation from political agency. This liminality pushed some peasants further towards the countryside, while others converted to factory work. Those who couldn’t find a new profession in this new scarred landscape often spiralled into poverty, criminality, and substance abuse. As Addy stated in_ Memoirs Against Forgetting_: "Ujungberung experienced a great culture shock. When productive agrarian lands were transformed by foreign investors into pollutant-laden industrial territories, the culture of farming, thick with communal nuances, drastically changed into a culture of labourers who systematically became asocial beings. This had an impact on society’s behaviour in general. Local interests’ conflicts rose. The youth, part of a community structure, responded to the problem by looking for channels of expression representing their feelings’ turmoil. So metal was used as a medium of expression that is considered in accordance with their unrest. Fast, aggressive music and sarcastic protest lyrics became their escape."

The expression of the anxiety generated by these difficult social conditions was metal. Metalheads’ experience of trauma, expressed and dramatised through music, tethered inhabitants to territory, helping them to tap into the transnational, class-based backbone of the subculture. Metal as a sonification of inequality began in a post-industrialising Birmingham where Black Sabbath and Napalm Death were screaming of bleak existences confined in council flats and underpaid factory shifts. As their sound circulated, it resonated with similar realities of urban industrialisation and precarity worldwide. By listening to metal and using Ujungberung as a prism of extreme experiences, Bandung metalheads could see the world. Metal offered a gateway to conceive of globalisation as a sum of marginal localities, where crises connected countries and social groups with similar histories and contexts. As Addy commented in an interview with me: "For me, metal’s extreme is in how bands expressed themselves. The first time I heard Sepultura [...] They are from Brazil! A third world country. They have social problems… So many problems, and they were expressing it in their music. [...] And that related with my life, with my experience of Ujungberung.

This shows how metalheads conceived the world through a political imagination mediated by metal records’ sense of extreme. Ujungberung resonated with Brazil and, possibly, other "third world countries," framing music as an axis of alliance between people and places facing similar difficulties. Ujungberung’s changing landscape generated a middle space, a borderland between modernity and tradition, locality and globality. As Hinhin Daryana, ethnomusicologist and member of Bandung death metal band Humiliation attested, metal arose specifically as a response to the increased blurring of identity caused by globalisation.

To state it otherwise, the metal scene’s inception acted as a sonification of a geo-traumatic experience generated by land transformation into an ambiguous space. Geotrauma is a term coined by philosopher Nick Land,2 inviting psychological analyses to go beyond the terrain of familial drama and include the socio-political realms of the geographical, the geological, and the cosmological. Beyond philosophy, recent sociological and psychological employment of the term highlighted the role of oppressive power relations in various collective forms of trauma expressed in tandem with territory. Conceptually, these violent inscriptive processes leave a trace of themselves both on a territory and its inhabitants in a feedback loop. Accordingly, the territory is viewed as more than just the target of human conflict. As outer ecological relations form the human world, violence is reflected back on humans. Geotrauma, then, describes the relational grasp of a place with the impacts of trauma. In Ujungberung metalheads’ narratives, capitalism changed the landscape, which changed the people. Coherently with the history of metal’s globalisation, blue-collar geographic desolation created the existential dread which only metal music could express.

In Ujungberung, metal satisfied an affective overdrive that arose from an extreme situation—a need to process geotrauma—transforming an existential wound into life-affirming energy and allowing metalheads to reacquire control over their lives and their geographies. The suffering of the earth and its spinal consequences on human and non-human inhabitants were transduced by razorlike gains and otherworldly screams. The throat, the drum, the string became vectors circulating this message made of extremely pressurised air. Exceptionally, through metal, Ujungberung’s impoverishment was converted into the mythological landscape of the biggest scene in Indonesia. Speed, volume, and distortion created a core sense of the overwhelming, allowing a transformative overload of cathartic energy. The genre was a sonified antagonism to capitalist exploitation through dedicated DIY participation, independent production, and anarchist activism.

Interestingly, such connections do not talk explicitly of tradition, as these projects’ outlook on socio-political issues only conceive locality as part of a network of places. For Ujungberung metalheads, the industrialising countryside was no more traditional than a de-industrialising urban Birmingham; two faces of the same coin given how Western de-industrialisation processes were nothing else than the relocation of production to emerging economies like Indonesia. Nonetheless, this relationship to agrarian imagery has remained a strong outpost of political commentary in the work of some bands. This is the case of the anonymous black metal band Bvrtan, which by impersonating agrarian workers from the West Java hills denounce state corruption with works such as Koperasi Kegelapan yang Memonopoli Ekonomi Pedesaan (the dark cooperative who monopolises the village economy). In a similar vein, the brutal death metal outfit Sufism sing about a long-lost communitarian landscape of agrarian simplicity taken away by human-eating factories, while the atmospheric black metal one-man band Pure Wrath retells histories of exile and structural violence suffered by peasants during the genocide.

|

|

|

|---|---|---|

Album covers from some of Indonesia’s metal underground

Left: Pure Wrath, Painting by Aghy Purakusuma, Lay-out by Januaryo Hard

Middle: Sufism, © Aghy R. Purakusuma

Right: Bvrtan, © Bvrtan

Overall, such connections to place and political agency show that the "sound of metal" produced a sonic ecology based on hyperlocality: a space formed and modulated by social music. In his book Teklife / Ghettoville / Eski, scholar Dhanveer Singh Brar theorizes how Black UK electronic music generated new sonic productions marking out the race and class geographies of particular cities, transforming the musicians’ geographically concentrated musical antagonism into a sonic ecology: a non-equivalent correspondence between music, society, and geography. Shaped by the urban working class of each particular locality, which infuses the respective musics with an impetus of self-determination, the genres examined by Brar gave the impression that they were a response to, or an effect of, a sustained period of urban crisis. Each soundscape was injected with a strong sense of territory, creating distinct countervailing renegade movements.

Whether formed by metalheads in Bandung or Black communities in London, these sonic ecologies became intensely reshaped through everyday underground aesthetic practices operating within precarious urban zones. Artists were able to reconfigure their place in the city and regain power and agency both on the urban territory and its society, if nothing else, by becoming acclaimed superstars. It’s during this moment of maximum recognition worldwide, from these conceptual localities they had reshaped, that the Indonesian metal scene stepped into ethnolocality.

Underground Traditions and Extreme Ethnolocality (2000-2020)

With Suharto’s collapse under the weight of youth riots and dissonant chords in 1998, political reforms attempted to change governmental structures through a decentralisation based on regional autonomy. This transition resulted in the emergence of regional, independent music industries on different islands. Local productions grew by targeting specific communities such as ethnolocalised social groups, and spurred among other several "local takes" on cosmopolitan genres through vernacular and ethnic languages. This included extreme metal.

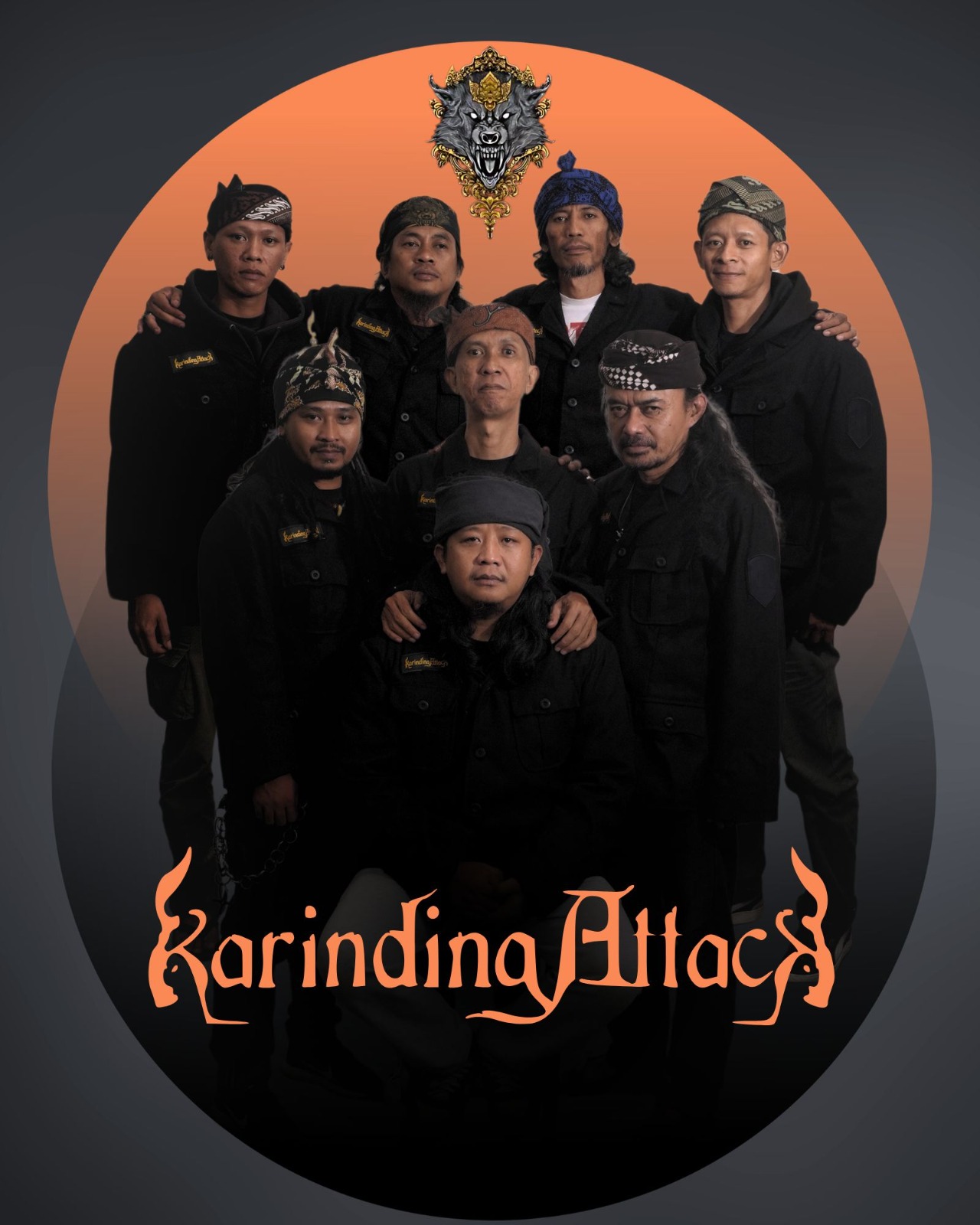

Despite the excellent local conditions to implement local heritage into music productions, according to Kimung, founder of metal bands Burgerkil and Karinding Attack and Bandung metal scene’s most active historian, the decision to explore ethnolocality came from the fact that worldwide, the early 2000s global metal scene was rooting itself into local heritage and knowledges. When bands like Brazilian Sepultura explored experimental collaborations with the Indigenous Xavante people as a wider strategy of bottom-up social struggle, Bandung metalheads felt like they had to contribute too.

Additionally, the political landscape had changed. This time, in Indonesia, politics were supporting regionality, and metal had become an acclaimed phenomenon among the people. Hence, the key to the participation in a global movement was found in regional, ethnolocalised practices; the logic being that according to Indonesian metalheads, new metal scenes in the early 2000s had a set of shared principles, including ethnolocal elements. Musicians from the Ujungberung Rebels started introducing markers of Sundanese ethnolocality such as clothing and regional language, and integrating traditional art forms and instruments in their music and events since 2003.

Although re-exploring ethnolocality could seem an opposition to globalisation’s cultural homogenisation kickstarted by the internet at the end of the 1990s, the reality is different. Bandung metalheads were reproducing a global pattern that included musical, text, and visual markers of ethnicity and ethnolocality. For the Bandung scene, this was an occasion to contribute to a global discourse on the ethnolocalisation of metal and to counteract what they perceived as an erasure of local customs on the one hand due to government policies during Suharto’s regime and on the other due to the Global North’s domination on the metal circuit, which ignored their existence. Most interestingly, the Bandung metal scene’s re-encounter with local aesthetics and heritage meant at once reimagining identity, "becoming Sundanese", and rewriting a neglected part of history left for dead by national institutions, through the lens of the underground.

In Bandung, this task was especially taken up by projects Jasad and Karinding Attack (aka Karat). With their 2013 album Rebirth of Jatisunda, a work dedicated to Sundanese history and spirituality, Jasad put Sundanese extreme metal on the map. The album lyrics, mostly written in an ancient metaphorical and esoteric form of the Sundanese language, explore various regional themes and characters such as Pajajaran’s legendary Sundanese king king Prabu Siliwangi, or specific principles of Sunda Wiwitan, a pre-hindu ethnolocal form of spirituality. While Jasad showed how canonical extreme metal could incorporate Sundanese-ness through language, myth and history, and compositional techniques, Karat, an ensemble composed by nine members of some of the iconic death metal outfits from the Ujungberung Rebels collective, imagined how Sundanese bamboo music could bring metal and traditional styles together, thus refuting an image of the Sundanese arts as a leftover of agrarian backwardness while expanding the extreme edges of metal.

Rebirth of Jatisunda by Jasad

While interested in bamboo instruments and their musical traditions, Karat focused especially on the karinding: a Sundanese mouth harp played by flicking the tip of the forefinger while keeping it in between the lips, usually made from palm fronds or bamboo. Traditionally, the karinding was played by peasants and villagers for personal amusement, and was believed to be able to chase away field pests. According to Man, singer and founder of Jasad and Karat, it is the instrument’s agrarian past and its current unpopularity that made it a symbol of both Sundaneseness and the underground: "When I became a metalhead, I had to follow American and European bands. But then I thought, if I follow these people, I will become a follower forever, so I tried to learn about Sundanese culture. [...] In 2009, because before I had never heard any karinding or celempung recorded on an album, I had no reference to make karinding music. So I asked some metalheads friends from Ujung Berung, why don’t we make a band for bamboo instruments? Until now we only have panguyuban [associations] and padepokan [shrines]. Let’s make a band but only bamboo. Unpopular bamboo instruments: celempung, karinding, toleat, angklung réak [buncis] [...]. We were not using angklung or calung because it was very familiar here for Sundanese culture."

Given metalheads’ self-fashioned position as anti-establishment and on the margins, it was natural of them to find less popular regional arts like the karinging alluring, as they were to the national narratives of tradition what the underground was to the mainstream. According to Kimung of Karat and Burgerkill, what caused the disappearance of the karinding was its association with communist institutions and their alleged popularity among regional communities. Conversely, as Man explained, instruments like the angklung and the calung were already promoted by Suharto as pan-Indonesian—cultural tools useful for propaganda. Overall, learning about Sundanese culture was a way to refuse the hegemony of the global metal circuit as well as to counteract state repression of ethnolocality.

Additionally, Sundanese tradition retroactively provided a foundational myth for the Bandung metal scene’s specific subcultural belonging. Underground performers like Karat grafted selected Sundanese values onto global popular music and vice versa. Musically, Karat took advantage of coincidental surface sonic similarities, including the karinding’s similarity to distorted, detuned guitars (pitch and timbre) and the celempung’s capacity to produce metal-like percussion parts (speed and rhythm) to fuse Sundanese aesthetics with an already popular youth movement: international death metal. Karat and Jasad thus worked as musical supercolliders of global and regional in a way that magnified the vernacular power of these cultural and subcultural forms in the eyes of the nation. Metal had become a local tradition, and Sundanese practices accessed modernity. The experiment worked. Not only did extreme metal communities revive the karinding’s popularity, but they inspired new outfits to try the same thing, as testified by bands such as KarindingKeos and Karinding Siliwangi.

|

|

|

|---|---|---|

Left: Karinding Attack, © Ryan Herdianan

Middle: Jasad, © Asep Budiman

Right: Undergod, © Undergod

If this was the way the first generation of Indonesian metal pioneers dealt with tradition, Undergod, a second generation brutal death metal band from Ujungberung shifted the focus from implementation to collaboration. Unlike Jasad, Undergod appeared in the early 2000s, a landscape in which promoting Sundanese metal was already the norm. As representatives of a second-wave of metal musicians, Undergod have worked with founders of the Ujungberung Rebels to revive interest for Sundanese culture locally.

During our first interview, when I asked him to tell me a bit about their story, Kinoy promptly took out his smartphone, showing me an eight-minute long video made in 2009 for a music broadcast named Reaksi Bandung (Bandung Reaction), titled "Launching Undergod." The video shows band members alternating between metal and traditional arts such as réak, debus, and karinding. In the video, Kinoy states, "We have organised the event with the help of friends in the metal community, to show kids their culture. It might be the first event that boosts and makes West Java’s culture alive."

By combining acts by traditional performers and metal musicians, the event embodied the possibility of these two different musical ecologies to coexist. But what distinguished Undergod from Jasad specifically was that, whereas Jasad used high level Sundanese and treated spiritual matters, Undergod were talking of Sundanese everyday life at the city peripheries; of heartbreak and gangsters and personal revenge. For Undergod, singing in Sundanese was an explicit way to invert the power dynamics engendered in the micropolitics of the global metal scene.

Although metal is still prevalently sung in English, a signifier of both the genre’s transnationality and geopolitical hierarchy, this does not entail an equal distribution of linguistic proficiency. Reminiscent of the band’s frustration while trying to grasp the meanings of lyrics they liked, Undergod decided to use this very same linguistic disappointment as a tool to spread knowledge about Sundanese culture. As Kinoy has stated in an interview with me: "We wanted to write in English, but we would listen to Metallica and not understand anything. We were constantly like: 'What’s this word? What does this mean?' So, we thought, maybe we can sing in Sundanese, so other people can perceive the same thing. Now it’s you that don’t understand and must ask: 'What does this mean?'"

Once again, it’s foreignness that invited Sundanese bands to articulate ethnolocality, to "become Sundanese." Yet, they could have, just as Jasad, simply composed music in Sundanese, without adding accompanying traditional performances. So why réak? Kinoy answered that aside from his wish to engage with traditional culture, both réak performers and metalheads used to hang out around the same soccer field near his house in Ujungberung. Moreover, some of the members had participated as members in réak Balebat Pakidulan, Ujungberung’s oldest réak troupe, which I introduced at the start of this article. Therefore, the choice for Undergod was not one of an "objective" artistic and geographic representation, for which choosing any of the local genres would have been a more suitable option, but one of proximity and familiarity. For Undergod, ethnic identity and its signifiers, language levels, gangster storytelling, and collaboration with réak troupes, are not abstract symbols, but a musical codification of lived experience. Just like the choice of themes and language reflect the everyday life of Kinoy and Ujungberung’s inhabitants, choosing réak was based on celebrating a proximate tradition concretely part of their experience. And yet, how are these traditional musicians reacting? If metal has indigenised, has réak become cosmopolitan?

Réak is a dance and music performance which originated in Bandung. It is a subregional variant of horse trance dances: a group of pan-Indonesian performances known under various names such as jaranan and jathilan. During the event, usually organised to celebrate human milestones like circumcisions and weddings, a trance master (ma’alim) coordinates spirit possessions of performers and audience members with the musical accompaniment of an ensemble of wooden single-head conical drums (dogdog) and a shawm instrument (tarompet). Each troupe is composed of 15 to 30 people, usually mostly male blue-collar workers as réak is believed to be a violent, masculine performance.

During réak the stage (the host’s backyard) is prepared early in the morning with offerings for the Karuhun: human ancestors’ spirits. The performance starts at 9AM with an overture. After a phase of freeform dance, the ma’alim indicates that the area has filled with enough power and that spirits are attending. The music’s tempo doubles, and the mischievous animal spirits Karuhun and Jurig Jarian are invited by the ma’alim to take control of the individuals to deliver messages to their relatives, perform dances, or show off their powers by chewing glass, devouring live chickens, and so on. Subsequently, a dancer is helped to enter and dance the Bangbarongan, an anthropo-zoomorphic costume and tutelary spirit. Wearing the costume implies the eventuality of possession, thus requiring performative and spiritual preparedness. After a parade around the village and a second performance at the host’s house, the event finishes at 5PM.

When I asked attendees what they liked about réak, they often replied that it is especially the horror and comedy offered by the spirits, the chaotic mosh-like social-ambience, and the ear-shattering, energising music. Given the focus on the supernatural and the overpowering sonic features, it’s not hard to imagine why metalheads have slowly become an integral part of the audience.

Born as an agrarian regional performance for celebrating human milestones, réak and its performers now exist in a landscape of mass-consumed popular music, from indie to hip hop. Given the aesthetic and class similarities between réak and metal, it is unsurprising that réak practitioners come as much from traditional music backgrounds as from the musical underground. This is particularly the case for Balebat Pakidulan, who have collaborated most often with Undergod.

Composed mostly of very young performers aged between 13 and 25, which is much younger than the middle-aged men that usually make up these groups, Balebat Pakidulan are known for conjuring spirits in their wildest versions, thus being dubbed by metalheads as the most extreme réak troupe. Members of Balebat Pakidulan have also founded two hardcore punk bands, Crack and Bottled Violent; outfits which, faithful to the movement, denounce the corruption and dominance of state authorities. What’s more, metal’s transnational character has influenced every aspect of this specific troupe, from uniforms designed by punk and metal illustrators, to their way of performing réak, which includes practices similar to stage diving and moshing. Their performances both maintain an important ceremonial function of renewing connections between the community of human and non-human entities, while at the same time making space for youth and subcultures to thrive and amplify the turmoil of informal, grassroots politics. While older, more authoritative réak groups focus on the way réak shows respect towards authority, the human, or the supernatural, Balebat Pakidulan like réak "because there are no rules" and "because we can show unity, protect our communities, and show who we are. It’s free expression." Their comments often come out with proud smirks and the occasional unapologetic, mischievous stare proper of those who know that musical crowds can become weapons.

Utopia Banished: Coda (2020 - ?)

If they’re so appreciated and supported by metal audiences, why do Balebat members mainly play in punk bands? Far from being a coincidence, this preference brings the history of this "traditional underground" full circle. While Bandung’s oppositional music subcultures had started as a social device to oppose oppressive national institutions, enfranchising with other underground phenomena notwithstanding their musical genre of choice, many things have changed. The politically charged musicality of metal bands has apparently vanished in contemporary Bandung, absorbed by corporate sponsors, mainstream media participation in television programmes and—as seen by the behaviour of president Jokowi who on the one hand has worn a Napalm Death t-shirt, while on the other attempted to place members of his family into political positions by changing the constitutions shows—even collaborating with political propaganda.

On the contrary, the "No Masters / No Slaves" attitude of punk has remained relatively unscathed and unpolluted by money and politics. Balebat were the only metal group to participate in recent protests against mass evictions in Bandung, alongside alternative bands from punk to noise to shoegaze. If "all music genres can be categorised as underground if the genre or band adheres to underground methods," as quoted in Rottrevore Mag in the 1990s, then these subcultures’ political stance has metastasized into Bandung’s traditional movements, which are today as inspired by the caveats of the ancestors as much as by Fugazi lyrics.

In this piece, I have tried to show how ethnicity, locality, tradition, and cosmopolitanism are not isolated phenomena but mutually influenced movements thriving on multi-generational exchanges based on the need to mobilize communities and establish genealogical affiliation between seemingly unrelated youth phenomena, that are in this case connected by a predilection for distorted, loud sonic overdrive. If nothing else, watching the phenomenon grow through the decades, we can see how loud popular music, identified first as an enemy of tradition and then as a product to disempower regional communities, has always fueled social spaces in which a lesson of resistance and opposition flowed from metal and punk to traditional music and back to the underground.

Now, the challenge of these subcultures, whether ethnolocal or cosmopolitan, is to remain relevant in an era when musical transgression is no longer a threat but a commercial asset. In the past, Bandung’s musical subcultures achieved one of the most difficult goals: to succeed in imposing themselves and their lifestyles on a totalitarian state that wanted them to be marginal losers—but at what cost? There is no answer yet. These lines only serve to remind us all that cultural resistance is possible. Returning from a year of research in Bandung, the center of clashes between students and state forces from the 1970s to the 2020s, I can say that when opening social media and seeing videos of protests against Indonesia’s increased militarisation following the election of new president and former general Prabowo Subianto, demonstrations against evictions or government "development plans," politically-engaged traditional performances, or independent coffee plantations unaffiliated with unfair land-use laws, a Sepultura t-shirt or a Minor Threat patch will pop up.

Bio

Luigi Monteanni is a PhD candidate in music studies at SOAS (London) under the AHRC CHASE funding scheme. He currently studies the indigenisation of extreme metal in Bandung, Indonesia, alongside theories of sonic ecologies and aural models of intensity. He is also the co-founder of Artetetra Records.

This text was commissioned as part of CTM 2025.

-

The Sundanese are the second biggest ethnic group in Indonesia after the Javanese, generally inhabiting the Western part of Java. ↩

-

Nick Land, one of the main figures of the accelerationist philosophical movement and founder of the CCRU alongside Sadie Plant, has in the last decades become a controversial character inspiring the global alt-right, evolving into reactionary and even neo fascist thought. His ideas should therefore be read with this in mind. Recent research and works by thinkers such as Urbanomic’s Maya B. Kronic and Rachel Pain have elaborated on these ideas while trying to move away from the philosopher’s reactionary foundations. (https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0309132520943676) ↩