Rewriting Slovak Folk Traditions in Fraught Political Times

While much reporting on European cultural scenes grappling with nationalist populism focuses on the dramatic shifts in Hungary, Slovakia presents a troubling continuation of this pattern, a heart-of-Europe case study in identity politics gone awry. Here, state-engineered attempts to redefine tradition and cultural heritage isolate and polarise society through manufactured narratives. The country's rightward pivot away from liberal democracy reflects a broader Central European pattern, where the manipulation of cultural identity serves as a tool for political transformation.

"The culture of the Slovak people should be Slovak, Slovak, and no other,"1 declared Martina Šimkovičová, a nominee of the ultra-nationalist Slovak National Party (SNS) and the Minister of Culture in 2023, as she outlined her vision for the Ministry during her first months in office. Before entering politics, Šimkovičová worked as a television presenter, but her broadcasting career ended following controversial social media posts expressing anti-refugee sentiments.In 2015, her views attracted the attention of the Slovak Inštitút ľudských práv (Human Rights Institute), which nominated her for their "Homophobe of the Year" award. Upon assuming her ministerial role, Šimkovičová made the contentious decision to restore Slovakia's official cultural ties with Belarus and Russia—ties that had been severed in 2022 following Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

Later, alongside the Secretary of the Ministry of Culture, Lukáš Machala, she expanded on her nationalist vision, advocating for the need to define cultural identity clearly for the coming decades. Under this framework, only those deemed "compatible" would be permitted to remain within state cultural institutions.2

This has raised significant concerns about the future of Slovak cultural policy under Šimkovičová's leadership, particularly as it aligns with a broader nationalist agenda and the way it mobilises cultural traditions. Šimkovičová's statements rejecting what she calls "progressive normalisation," while advocating for a return to normality and tradition, position her as a defender of traditional and authentic folk culture. In her rhetoric, anything Western is perceived as embodying decadence. The policies she represents are simultaneously commodifying these very traditions, remixing them to serve specific purposes and converting them into political capital for the current coalition—a government that openly expresses admiration for contemporary Russia and describes progressive thinking as a "cancer of society."

This approach reflects an effort to redraw cultural identity and history. In such an environment, the state positions itself as the sole authority on "preserving" folk culture and as the guardian of tradition. Instrumentalisation of culture and tradition is not new to us in Slovakia, and had been employed by the previous regime as well. It operates using an idea of tradition that is frozen in an imagined past, devoid of dialogue with experts, artists, or the living bearers of cultural heritage. Within this politically distorted concept of culture, cultural traditions and national identity are framed as having been formed in isolation, untouched by external influences.

The "return to traditions" appears less focused on exploring or preserving cultural heritage and more on creating marketable narratives of national uniqueness that can be exchanged for political, social, and economic benefits. But these benefits serve only a narrow group of people. A recent example is the latest update of the national anthem by the producer and conductor Oskar Rózsa, commissioned by the Minister, certainly in part due to their friendship, without wider discussion with the professional community. Among others, Rózsa has frequently appeared on pro-Russian and fake-news channels, and he is publicly associated with a prosecuted neo-Nazi. As a response to criticism over his non-transparent Ministry-funded fee,3 Rózsa commented that his version of the anthem was not meant for everyone (for which he later apologised). The new version of the anthem, which premiered on 1 January this year, the anniversary of the foundation of the Slovak Republic, has received mixed reactions. Its opulent orchestration, poorly balanced blend of vocal and instrumental components, slowed tempo and deliberate new-age tuning at 432Hz—purportedly to connect with the natural resonance of the universe—verge on kitsch.4 While national anthems traditionally serve to unite, the Slovak rendition appears to have achieved quite the opposite.

Behind this Potemkin-like façade, 5 where tradition and folklore are treated as immutable monoliths frozen in time, a different movement has emerged. In recent years, the grassroots experimental music scene has actively reimagined the relationship between tradition and contemporary identity. This scene understands cultural identity as a living, evolving entity that develops and transforms through its engagement with the present. Folk traditions, songs, and traditional musical instruments are not treated as untouchable or immune to change. Instead, they are recontextualised through the use of contemporary tools, such as electronic and club music, field recordings, improvisation sessions, sound art, storytelling, or just a basic MIDI protocol.

Importantly, tradition is not approached as a binary choice—either uncritical acceptance or outright rejection. Rather, it is embraced as a critical tool for understanding personal history within the present context.

The Not Compatible Ones

One of the most distinctive voices in the contemporary Slovak experimental music scene undoubtedly belongs to Adela Mede. Her work waves a multilingual identity, intertwining Slovak, Hungarian, and English to trace the rich geographical trajectories and cultural memory. This manifests in her ethereal vocals, which seamlessly integrate experimental electronics, field recordings, contemporary composition practices, and the poetics of Eastern European folklore. Adela's personal geography reflects the complex cultural flows of contemporary Central Europe: growing up on the Slovak-Hungarian border, caught between two nationalities with a historically complex love-hate relationship, then studying in London before returning to Bratislava

Despite growing up in a family deeply connected to folk traditions—her parents performed in a Slovak-Hungarian folklore ensemble—Adela's own relationship with these cultural roots only crystallised during her time abroad. "It was only there that I realised I was Eastern European,” she reflects. "That I’m not just an international student who speaks fluent English."

After returning to Slovakia, Adela began teaching singing. "I discovered a new kind of beauty," explains, "that arises when students, who may have forgotten techniques or never mastered them, immerse themselves in singing through their own emotion and enthusiasm." This raw connection to emotion is strongly present in her latest album, Ne Lépj a Virágra (2023). The album cycles through seven tracks, layering a solitary, drawling voice that evolves into varied song arrangements that remain aesthetically and thematically consistent. The first track, "Sing with Me," was originally written for one of her singing students. Intimate vocal performances are complemented by collaborations with fellow musicians Martyna Basta and Wojciech Rusin. "It was important for me to collaborate with people who understand my position and the emotion that comes from it." This transition from personal expression to collective experience highlights her artistic approach.

"My approach is still far from ethnography," she says. "I engage with the narratives of folk songs sensitively, through the emotions they communicate. The knowledge these songs convey can still speak to the present." Adela rejects the idea that tradition and identity are static concepts; instead, she views them as fluid, constantly evolving, intersecting, and changing—an understanding that challenges the rigid frameworks often associated with folklore.

"For a while, I was part of a small Slovak-Hungarian choir, where I strongly felt the attempts at nationalism," Adela recalls. "We had to sing the Hungarian national anthem or perform with our eyes closed. I had to leave."

For Adela Mede, folklore serves as a means to process the complexities of Hungarian heritage. Slovak-Hungarian relations carry a complicated shared history, laden with questions of national identity, territorial integrity, and historical grievances. These tensions date back to the monarchy period when Slovaks lacked political representation and faced Hungarianisation. Today, this history is often politicised through nationalist narratives that position the Hungarian minority in Slovakia at the centre of political disputes, particularly regarding language rights. "I can hide my identity behind my physical appearance, but I can’t hide my language in the same way. For a very long time, I worked to ensure there was no Hungarian accent in my speech. This complicates communication with my parents, whose native language is Hungarian. I can’t develop many ideas at home."

"Hol A Tavasz" from the album Ne Lépj a Virágra by Adela Mede and Martyna Basta.

After completing work on Ne Lépj a Virágra, Adela began collaborating with composer and improviser Štefan Szabó to perform and record folk songs. Szabó, a prominent figure on the Slovak music scene, has been reviving traditional and folk music through communal and improvised performances that avoid universal narratives by bringing to the centre regionally specific ways of playing folk. One example is the fortnightly folk music series u strún at Romer's House in Bratislava, which builds on the tradition of dance halls by promoting an environment where music is enjoyed communally through dancing and listening, without the need for elaborate scenography and curatorial navigation. "Štefan is someone who makes me speak Hungarian," Adela adds with a laugh.

Ancestral Archaeology (2022), an album by Nina Pixel, explores tradition from a different perspective, processing folklore through the lens of contemporary club sound by merging techno with dark ambient. As the title suggests, the album acts as an excavation of Slovak cultural memory. It began with a study of various folk song genres, drawing from collections of Slovak folk songs compiled by ethnomusicologist Soňa Burlasová.

Burlasová’s field research focused on folk songs tied to everyday traditions and events in rural life. As Nina Pixel delved deeper into these collections, she explored descriptions of superstitions and customs associated with paganism and white magic. Gradually, she began composing music and creating lyrics inspired by these elements, forming her own folklore in contrast to narratives where folklore was used to reinforce nationalist ideologies. "These narratives didn’t work for me," Nina Pixel explains. "So I thought, let’s create our own folklore—one that represents my culture, my identity, and that of my friends."

In this work, folklore is approached as a form of togetherness, with Nina Pixel drawing parallels between traditional community gatherings and contemporary rave culture. Samples from ethnographic recordings—funeral laments, hay-making songs, nursery rhymes, fragments from archival documentaries—are combined with field recordings from Slovak forests and the sounds of traditional instruments such as the fujara, a vertical wooden flute with a rich bass sound, originally associated with shepherds, or sheep bells. These are interwoven with the dance-like tempo of drum machines, creating a visceral, tactile quality. This combination of components envelops the album as a kind of forgotten artefact of past futures, found by chance under a layer of earth.

"A Goddess Comes From Within The Earth" by Nina Pixel.

By grounding the music in field, archival, and ethnographic recordings, Nina Pixel anchors the album in the physical world despite (or perhaps because of) its dense, club-driven sound. The hayfield and the club dancefloor merge as one. This interplay is not merely a superficial aesthetic experiment. Through it, Nina Pixel critiques the rigidity of viewing tradition and folklore as something narrowly defined. "There is such a liminal space for something else," she says, "something that leaves behind the expectation of how things should be done and performed." Her approach to tradition—transforming it and developing it into her own forms of folklore—welcomes both the personal and the intimate, while connecting these to the collective. This process, developed during the creation of Ancestral Archaeology, has carried forward into her involvement in shaping female circles. "We are a group of six women creating a shared folklore. We are a community with common cultural elements and language. We’re there for each other when we are heartbroken or need to manifest and create something."

This collaboration has culminated in 1111VV_god, a techno-noise project born out of a dialogue between Nina Pixel and noise producer Eva Kadmon. The project manifests the fluidity of identity, continuing Nina Pixel’s exploration of tradition, community, and personal expression.

Ancestral Archaeology builds upon the earlier project Liptov (2021), released by Prague-based Punctum Tapes—home to the community radio Radio Punctum, associated with the label. The album is a compilation of twelve tracks inspired, as implied by the title, by the traditional and folk music of the Liptov region—a basin bordered by mountain ranges in northern Slovakia.

During the second half of the 20th century, composer Svetozár Stračina and ethnomusicologist Viliam Ján Gruska systematically collected and archived songs and musical folk traditions of the region. Their field research culminated in the compilation Liptov—Panoráma ľudovej piesne a hudobnej kultúry, originally published in 1982. This collection featured 186 folk songs that accompanied the people of Liptov in their daily fieldwork, community and religious celebrations, family gatherings, and expressions of grief.

"Piesne Ťažkých Chvíľ (S Dobrým Koncem)" by Exhausted Modern from the Liptov compilation

The Liptov compilation directly engages with these archival recordings, reinterpreting them through the aesthetics of contemporary experimental music producers closely associated with the Radio Punctum. The project brings together a group of Slovak, Czech, and British artists such as Oliver Torr, Evil Medvěd, Andrea Beton, Trauma, Exhausted Modern, Obelisk of Light, Nina Pixel to deconstruct and reassemble Slovak folklore through ambient, drone, and techno soundscapes.

"What was served to my generation was a fully castrated mutation of folklore that fulfilled a certain representational function for whoever it suited," says Tomáš Ferko of Punctum Tapes. Here, the reinterpretation opens up space for the contemporary sounds of electronic and dance music. "In both cases—folk and electronic music—it is often the immediate cultural expression of people without classical training. The main roles here are shared musical intuition, enjoyment, and dance, and these are built on a fairly egalitarian basis."

The tradition of working with ethnographic recordings continues on Blurry AF (2021), the latest album by producer Isama Zing. On two tracks, Isama Zing recontextualises traditional Romani helgato songs, weaving introspective, almost tender melodic layers into a dense, contemporary post-club sound while maintaining a cinematic quality.

The album opens with "Žehra," a collaboration with producer Aid Kid. This track builds upon Irena Pokutová's helgato from the archival recordings of ethnomusicologist Jana Belišová, a key figure in documenting Roma music in Slovakia. Helgato is a style of song characterised by its balladic nature, slow tempo, and deep emotional content. It focuses on the struggles and hardships faced by the Roma people. Typically performed a cappella or with minimal musical accompaniment, helgato serves as a medium of memory, expressing through song the challenges, desires, and resilience of a community that remains marginalized to the present day.

Helgato appears again on the track "Blurry." Here, the archival recording merges with the deconstructed sound crafted by guest artist Oliver Torr.

The opening track "Žehra" from Isama Zing's album Blurry AF.

"I think this music holds the strongest emotional mark within our region," Isama Zing explains. "The strength of that emotion had the potential to continue being recontextualised. That’s why, perhaps even a drastic use of autotune on the track 'Žehra', can carry the meaning of the recording further, albeit in a different way."

Despite the sensitive nature of the archival material, Isama Zing supports its reinterpretation. "Our country is largely segregating the Roma community. It was therefore important for me to put these songs into a contemporary context. These songs have been passed down orally, from person to person, continuously being renewed and reinterpreted. I believe culture fundamentally carries this essence—it evolves and changes."

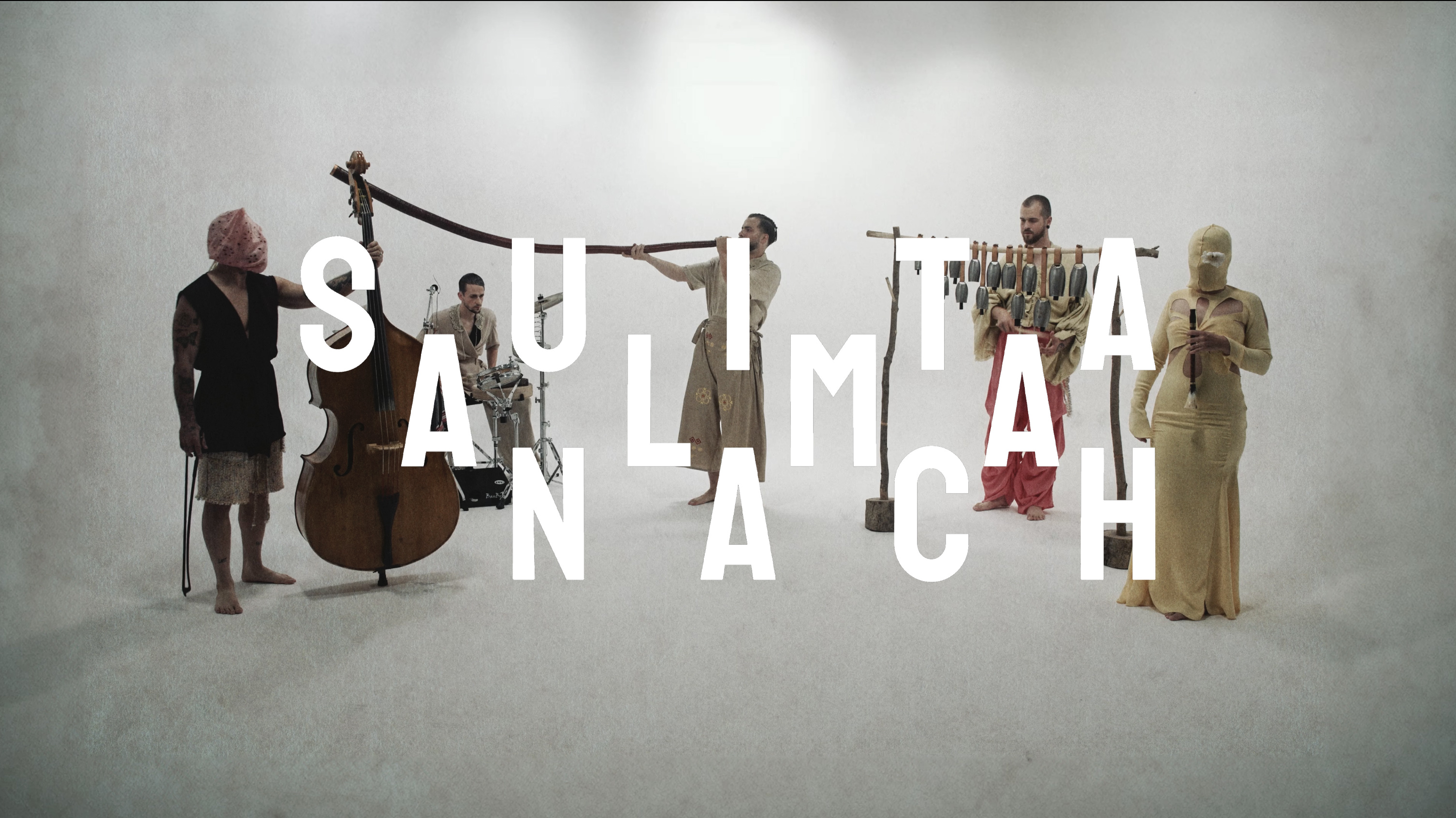

While earlier releases fuse the folk music tradition with the dense sound of contemporary electronica, Štefánik’s self-released Suita Almanach (2023) takes a different approach, situating these traditions within the practices of sheet music. The album features five compositions that explore the perception of the year through the lens of folk traditions. It introduces the listeners to Slunovrat, the solstice period, symbolising the rebirth of light; Priadky, associated with female singing, storytelling, and love ceremonies; Stridžie dni, with its ceremonial rituals to ward off malevolent forces; the period of Christmas; and Mjasopust, a time of cheerfulness and feasting.

Traditional instruments, such as the fujara, trombita, jaw harp, and gajdica, are reinterpreted using extended playing techniques and compositional methods characteristic of contemporary classical music. The aim is to integrate traditional instruments and practices into modern classical techniques in a way that treats tradition as an equal counterpart to the contemporary.

"I wanted to develop extended techniques for instruments historically present in the territory of Slovakia—techniques that would avoid viewing these instruments through the patina of the past—and to incorporate them into the sheet music," Štefánik explains. "My goal was to create compositions that could bring these instruments into the present day." For instance, the jaw harp was adapted to meet the compositional requirements of the album. In collaboration with Jan Šicko, it was redesigned into a MIDI instrument, where solenoids control the metal tongues of the jaw harp, replacing traditional percussion in the composition. This transformation gave the instrument a new voice through the application of technology typical for electronic music

"If you want to create something new in folk music, to take it further, you have to do something different for it," Štefánik reflects. "Just like Stockhausen or Boulez did in the context of Western music."

Štefánik performs on Drumblæ, an instrument he co-designed with instrument maker Jan Šicko that uses traditional jaw harps.

The album Sing Nightingale(2024), composed by flautist and percussionist Michaela Antalová and Norwegian double bassist Adrian Myhr, is loosely inspired by the traditional Slovak song "Zaspievaj, slávičku." The nightingale, a bird traditionally associated with young love, sacrifice, and loss, makes its home across the geographies of Central Europe, the Middle East, and sub-Saharan Africa. As a creature of the sky, the nightingale transcends earthbound boundaries—a quality reflected in Michaela and Adrian's collaborative work, which bridges traditions and practices from regions distant by land yet connected by air through folk sound.

"Just as the nightingale finds its home in different regions, musical instruments can draw inspiration from practices rooted in other cultures," says Michaela, noting that the evolution of musical instruments occurs not in isolation but through travel, carrying cultural specificities with it. "The violin, for instance, evolved from instruments such as the kamancheh or rabāb after they reached Europe, then travelled back to the Arab world to find its place there. It travelled just like the nightingale."

This cross-cultural exchange is evident in the track "Dole Ovce Dolinami," where Michaela's fujara performance is complemented by Javid Afsari Rad's Iranian santur, an instrument sonically akin to the Slovakian board-string instrument, the cimbalom. It seems fitting that the nightingale is also one of Iran's national symbols.

Through its eleven tracks, the album weaves together folk traditions from different regions, improvisation, elements of experimental music and the depth of Scandinavian jazz. "The album reflects what we have experienced as musicians," Michaela explains. "We come from improvised experimental music, which we complement with elements of folk, jazz, as well as composed and classical music."

"Dole Ovce Dolinami" from the latest album Sing Nightingale by Michaela Antalová and Adrian Myhr.

While political efforts in Slovakia aim to instrumentalise tradition and folklore—reducing their richness to serve nationalist agendas and turning them into fossils intended to raise political capital—the experimental music scene presents a compelling counter-narrative. This diverse community, spanning genres from club music to contemporary classical compositions, views tradition as a dynamic and evolving cultural heritage that belongs to everyone—not just the so-called "compatible" ones imagined by the Minister of Culture. The reinterpretation of folklore and embrace of its fluidity demonstrates how tradition can be updated to reflect contemporary reality whilst maintaining its relevance. Tradition is not a static relic but a living, breathing entity capable of adaptation, transformation, and inclusive expression. But this is only the beginning.

Is There A Way Out?

The Slovakian cultural sector continues to face numerous challenges: the dismantling of functioning grant systems in an already underfunded sector, the illogical and often revenge-motivated replacement of long-serving directors6 and other experts with "our people" in key institutions, the blocking of approved project funds, collaboration with authoritarian regimes, and an environment of unprofessionalism and intimidation. This deterioration, paradoxically accompanied by new versions7 of Rózsa’s new national anthem, offers little hope for better futures

Escaping into negative scenarios, however, does not have to be the only solution. Although the current political climate fosters instability, anxiety, and fear, it does not mean that we are living at "the end of history." The projection of dystopian futures often lacks persistence, imagination, and what Donna Haraway (2016) describes as "staying with the trouble"—a committed perseverance in difficult times. This active engagement with the present is manifested in the way the contemporary experimental music scene reinterprets folklore and heritage. Rather than rejecting tradition or accepting its political manipulation, the scene forges new approaches that acknowledge historical significance while embracing its flexible, inclusive, and ever-evolving nature. Tradition is not treated as a fixed set of practices, frozen in time, but as a dynamic process that navigates the interplay between past and present, local and global, continuity and change. But, they are not the only ones responding to contemporary issues.

In January 2024, a petition calling for the resignation of the Minister of Culture, Martina Šimkovičová, was launched in response to the systematic dismantling of cultural institutions, authoritarian practices, lack of transparency, absence of dialogue, manufactured culture wars, LGBTQI+ stigmatisation, and lack of vision. Between its launch on 17 January 2024 and its closure on 26 January, the petition was signed by over 188,000 people.8

The ministry responded to this with criminal proceedings, bizarrely claiming that signatures were coming in too quickly, even at night (the petition was signed online). In the wake of this public outcry and the growing arrogance and ineptitude of the administration9, a grassroots citizens' initiative called Otvorená kultúra! was formed in February 2024. Otvorená kultúra! connects cultural actors across established institutions, independent organisations, and freelancers while drawing attention to the broader problems of cultural policy and the precariousness of the sector. It is based on solidarity, mutual support, and the exchange of know-how.

In August 2024, the initiative launched a cultural strike in response to proposed changes affecting independent arts funds and public media10. These changes would fundamentally alter the functioning of these institutions, politicising them and placing them under the control of a small group of individuals linked to the Ministry of Culture and the Slovak National Party.The amendment to the Slovak Arts Council, the main funding body for the arts, is particularly worrying for the experimental music scene. The Council's agenda has included support for the production and release of experimental music, which in recent years has contributed to the release of albums by Michaela Antalová and Adrian Myhr, Adela Mede and Nina Pixel.

The amendment, which was passed by the Parliament without consultation with experts, significantly changed the Council’s mandate. The majority of the members of the Council, the highest decision-making body, are now directly appointed by Minister Šimkovičová. Instead of expert committees, funding decisions are now made by a council dominated by politically motivated members who can arbitrarily exclude "undesirable" actors while prioritising low-quality projects that fit their ideological agenda. These decisions are taken without any justification. This has already led to systematic delays in the Council's approval processes, as newly elected members—some of whom have yet to prove their cultural expertise, as required by law—fail to attend meetings.

But the cultural strike is not only a fight for the independence of cultural institutions. It is also a struggle for decent working conditions, adequate financial remuneration, and the protection of the rights of all those involved in the cultural ecosystem. The strikers form a network of solidarity, symbolising the collective capacity of cultural workers to resist pressure and demand systemic changes. These demands include professional and transparent management of cultural institutions, an end to ideological censorship, and financial stability for cultural workers.

These struggles have also led to the formation of cultural unions under the umbrella of Otvorená kultúra! in May 2024. The aim is to address the complex challenges facing the sector, particularly for freelance artists and cultural workers on fixed-term contracts. For many, going on strike is not an easy or viable option, as their livelihoods depend on unpredictable funding, commissions, and personal entrepreneurship. In this precarious environment, with inadequate social security and no single employer to target, unions aim to highlight the unsustainability of such working conditions and advocate for changes in public policy.

Meanwhile, the board of the Slovak Arts Council—which is dominated by members appointed by the Minister of Culture—has proposed a new statute for the operation of the fund. If adopted, this statute would increase the board's powers, abolish several areas of cultural support (including museums, galleries and cultural centres), and allow the Ministry of Culture to claim up to 25% of the fund's annual budget for its own "state priorities." This is accompanied by pro-nationalist PR, claiming that the changes will "increase support for Slovak culture."

Ironically, the draft statute also eliminates funding for folklore ensembles—the very traditions that ministry officials, often dressed in folk costumes, claim to be defending against "Western influence." This contradiction highlights how tradition is used as a rhetorical device rather than a real plan to protect and support. While officials make impassioned speeches about preserving Slovak cultural identity, their actions systematically dismantle the infrastructure that supports it.

These efforts to politicise the Slovak Arts Council have provoked widespread public opposition. Otvorená kultúra! was joined by the wider cultural community, local governments, mayors, and universities in a united call to preserve the public nature of the fund. In response to this pressure, the controversial statute was not adopted at the board meeting’s vote on 15 January 2025.

Meanwhile, large-scale civil protests have amplified these demands, calling for an end to the destruction of institutions, the erosion of the rule of law, and the reversal of the country’s political tilt towards Moscow. On Friday, 24 January 2025, for example, more than 35,000 people gathered in the streets of Bratislava.

Beyond the immediate crisis in Slovak cultural institutions lies a broader lesson about the relationship between tradition and power. The local experimental music scene demonstrates that when folklore and tradition become entangled with political agendas, artists and cultural workers can forge alternative paths. While state actors seek to fossilize traditions into tools for manufacturing consent, experiments in music show how cultural heritage thrives through reinterpretation. From Nina Pixel's club-driven ancestral excavations to Michaela Antalová's cross-cultural dialogues, the music demonstrates that tradition gains meaning not through isolation but through exchange and transformation. This form of resistance, coupled with widespread civic mobilisation through initiatives such as Otvorená kultúra! suggests that the battle over cultural institutions is a deeper struggle over who has the right to interpret and develop a shared heritage. As shown above, the powerful counter-narrative to nationalist myth-making is that tradition does not belong to those who claim to protect it, but to those who keep it alive through constant reimagining and collective engagement.

Bio

Ján Solčáni is a curator, sound artist, and theorist passionate about exploring culture through sound. They co-founded the label Skupina, organise the Videogram lecture series, and manage the Unseen listening archive. Ján also writes, hosts a radio show, and contributes to various projects for the Roman Radkovič Collective, all focused on rethinking how we engage with sound. Ján holds a PhD in fine arts.

In this text, references to specific political content aimed at social media audiences have been deliberately limited. This is to avoid increasing their audience and reach.

This text was commissioned as part of CTM 2025.

The circumstances outlined in the text reflect the situation as of February 2025, when the essay was first published. However, the present situation does not necessarily have to correspond with the condition of affairs as presented in the text.

-

Loosely translated from the original Slovak version: "Kultúra slovenského ľudu má byť slovenská, slovenská a žiadna iná." ↩

-

This statement was presented during a press conference held by representatives of the Ministry of Culture in August 2024. The recording, in Slovak, is available here. ↩

-

The controversy primarily stems from the lack of transparency regarding the handling of funding for the anthem. The total fee for its production was €46,500, with €20,000 allocated to the author’s fee and the remainder covering the recording’s production costs. However, the ministry has not provided a detailed breakdown of these expenses. Notably, the Slovak Philharmonic Orchestra performed the composition without receiving any royalties, and the boys’ choir, which sings the new version of the anthem, has to this date not received any compensation. ↩

-

Here I refer to the definition of kitsch as given by Tomáš Kulka in Kitsch and Art (1996). Kulka defines kitsch as a style that uses recognisable emotional triggers and accessible aesthetics to instantly elicit predictable sentimental reactions, rather than challenging perspectives or promoting reflection. It provides comfort through familiar conventions. ↩

-

"Potemkin village" is a term which describes illusory or superficial constructs designed to hide the true state of things or events. These constructs can be either physical or symbolic and aim to create a false impression of prosperity, order, or tradition, particularly in a cultural or political context. ↩

-

It is worth mentioning an open letter initiated by the international cultural community expressing outrage and concern over the dismissal of the director of the Slovak National Gallery. Available here. ↩

-

Following the premiere of the new version of the anthem and the resulting criticism, other versions appeared on the composer's YouTube channel. These included a version with emphasis on the vocals or another with a faster tempo for sports events. However, these were later removed from the channel. ↩

-

In the last parliamentary elections in Slovakia, which brought Martina Šimkovičová to the seat of a minister, she received 27,615 preferential votes. In the Slovak parliamentary electoral system, preferential voting allows voters to influence which candidates from a party’s list are elected. Each voter receives a ballot paper representing a political party, which includes a list of up to 150 candidates. Voters can circle up to three names, thereby granting them preferential votes within the party. Alternatively, they may submit the ballot without marking any names, which means they accept the party’s predefined order of candidates. This system enables candidates who are ranked lower on the party list to secure parliamentary seats, often benefiting well-known public figures such as celebrities, athletes, influencers, and other media personalities. ↩

-

A rather extensive list of failures, together with a description of them and their consequences, compiled by Open Culture! and the Culture Strike Committee, is available online in Slovak here. ↩

-

These include the revision of the law regulating the functioning of the Audiovisual Fund, the Slovak Arts Council, public television and radio, and the law on museums and galleries. ↩