Gambioluthiery: Hacking and DIY in Brazil

Introduction

The popular Brazilian expression gambiarra describes an improvised, informal way of solving an everyday problem when needed tools or resources are not available.1 Like “hacking” and “DIY” it reflects a way of dealing with the objects and issues that occupy the daily life of post-industrial societies, but gambiarra also denotes specific aspects of Brazilian culture. When applied to visual art, music, sound art and media activism, it describes ways how some artists choose to work with materials, technology and/or local institutions. Activities that reflect gambiarra approaches include instrument building, hardware hacking, cracked media, and other forms of technological activism2 —all suggestive of a re-envisioning of the musical instrument.

Gambiarra's Genealogy

Originally, in the 19th century, “gambiarra” referred to string lights (fig. 1). The word’s etymology is unclear, but it may have derived from gambia (leg) or from the expression dar às gâmbias, meaning "to run, escape, or flee."3 Popularly, the word variously means to fix, adapt, improvise or assemble; it can also refer to a handyman, to patchwork, to tricks, and to DIY. By extension it is describes extemporaneous approaches to problem solving; inventiveness, intelligence and creativity. It may also refer to vernacular, autochthonous, popular art. Or, more negatively, it can suggest taking advantage of a situation, or a behavior that is illicit, dishonest or fraudulent. Gambiarra is scruffy, precarious, rustic, crude, ephemeral, palliative, volatile, imperfect and unfinished. 4

This spectrum of meanings makes the term adaptable to various contexts. Gambiarra twists the logic of industrial design, establishing short circuits between a product’s form and its functionality. In principle, it emerges from an existing design but, depending on the degree of interference, it can also result in a new design object.

Other cultures sport similar expressions, of course: in Cuba Revolico and rikimbili refer to "technological disobedience," or resistance to the scarcity of material resources and technological access;5 in Mexico rasquachismo, an artistic movement working within technical and material limitations;6 in Uruguay chapuza, arreglo temporal (temporary arrangement) and lo atamos con alambre (tie with wire) represent quick and careless execution; solución parche (patchwork solution) in Chile means a kind of temporary amendment; and the Colombian arreglo hechizo or reparación hechiza have connotations similar to gambiarra. The practices represented by these terms reveal varied cultural responses to the practical benefits and limitations of technological product design.

Local Context: Carnivalization of Technique

Gambiarra, however, carries distinctly Brazilian associations. The idea of a plural culture that aimed to digest everything that comes from outside, incorporating and re-elaborating elements of global culture in their own way was taken by the artistic movements such as the modernist anthropophagic movement in the 1920s and revisited by tropicalism in the late 1960s.7 Cultural icons of local culture commonly related to the gambiarra approach include jeitinho, malandragem and the carnival. Perhaps the most iconic manifestation of gambiarra is carnival, with its characteristic freedom of expression and movement, and its subversion and the temporary inversion of the social hierarchy.8 Carnival’s inside-out, world-upside-down logic does not provide a permanent extinction of hierarchies,9 instead it dismantles the system of social roles for a short period.10 In art and music, gambiarra similarly subverts subject positions and the form-function of designed objects. The consumer assumes a temporary inventor role, moving from passivity to active creation, and imbuing extant products with new uses and purposes. It reverses the order of artifacts, serving as a carnivalization of technique, technology and design.11

Sound and Gambiarra

Despite radically different cultural contexts, European movements such as Elektronische Musik and musique concrète are similar to gambiarra in their substitution of nontraditional technological tools for traditional ones—for example, using radio transmitters as instruments. Experimental music has other connections to gambiarra: the presence of chance, an emphasis on process and the adaptation of tools such as prepared piano, turntables, or electronic test equipment.

Given gambiarra’s subversion and repurposing of found materials, it is easy to associate it with practices such as circuit bending and hardware hacking. When lack of resources and precariousness are a work’s foundational elements, the risk of failure, glitch and crack is high, as is the need for adaptation and repair. It demands creative openness to error and unplanned occurrences—conditions that permeate cracked media. Likewise, "dirty electronics" emphasize the exploration of invented instruments and prioritize gesture and social interaction.12 "Dirt" here refers not to substandard quality but to the practice of contradicting technology’s supposedly universalizing character to reveal aspects of the dream that lies hidden in it. Along similar lines, Paul DeMarinis has proposed rebuilding obsolete and absurd technologies, an activity that resembles gambiarra’s carnivalization of design.13

Gambioluthiery

“Gambioluthiery” is my neologism for the construction of instruments oriented around the logic of gambiarra, involving activities such as composing, decomposing, inventing, proposing, constructing, collecting, adapting and appropriating materials, objects, artifacts, devices, instruments or system setups. As such, gambioluthiery intervenes between the form and the purpose of objects and devices, resulting in new instruments, artworks and experiences. Gambioluthiery works in peripheral zones pre- or post- musical instrument, between the audible and visible, between musical performance and sound installations, and between musical projects and sound design. Exploiting sound beyond the syntax of traditional musical instruments, it emerges from a tension within the concept of a musical instrument and its material context. The boundaries between utilitarian object and instrument are confused, dynamic and unstable in gambioluthiery. It can be thought of as a practice of Tato Taborda’s concept of "technology without the edges"14, established via an upending of hierarchies between high and low technology or even between composer and interpreter.

The history of musical instruments is rife with overlaps between everyday tools and musical devices. Consider what unites and separates blowpipe and flute; the stretched rope of a bow and arrow and the string on a berimbau; a crate and a cajón; or a grater and a guiro. What distinguishes the mouth that eats from the mouth that speaks and sings? Gambioluthiery reconnects instrument and utilitarian object.

Gambioluthiery reinforces connections between sound and its materiality as well as the paradoxical gaps between advantage and limitations that techno-consumption produces globally. While I use the term to refer to a particular Brazilian repertoire (examples described below), it can be seen more broadly in the idea of expanding the musical instrument through sound art.15

Repertoire

A precursor on the route toward gambioluthiery is the Brazilian composer, cellist and luthier Walter Smetak (1913–1984), whose search for a new music was entwined with his invention of instruments meant to extend musical boundaries. Smetak’s musical and spiritual journey is summarized by the wordplay he used to describe the instrument as an object or vehicle that instructs minds: "instru- to instruct; ment- to mind. Instruct minds."16 From experimental luthiery to “plásticas sonoras” (sound plastic), extrapolated music proposed other spaces and methods for experiencing sound (installations, sculptures, objects and actions), which would later be defined as sound art.17

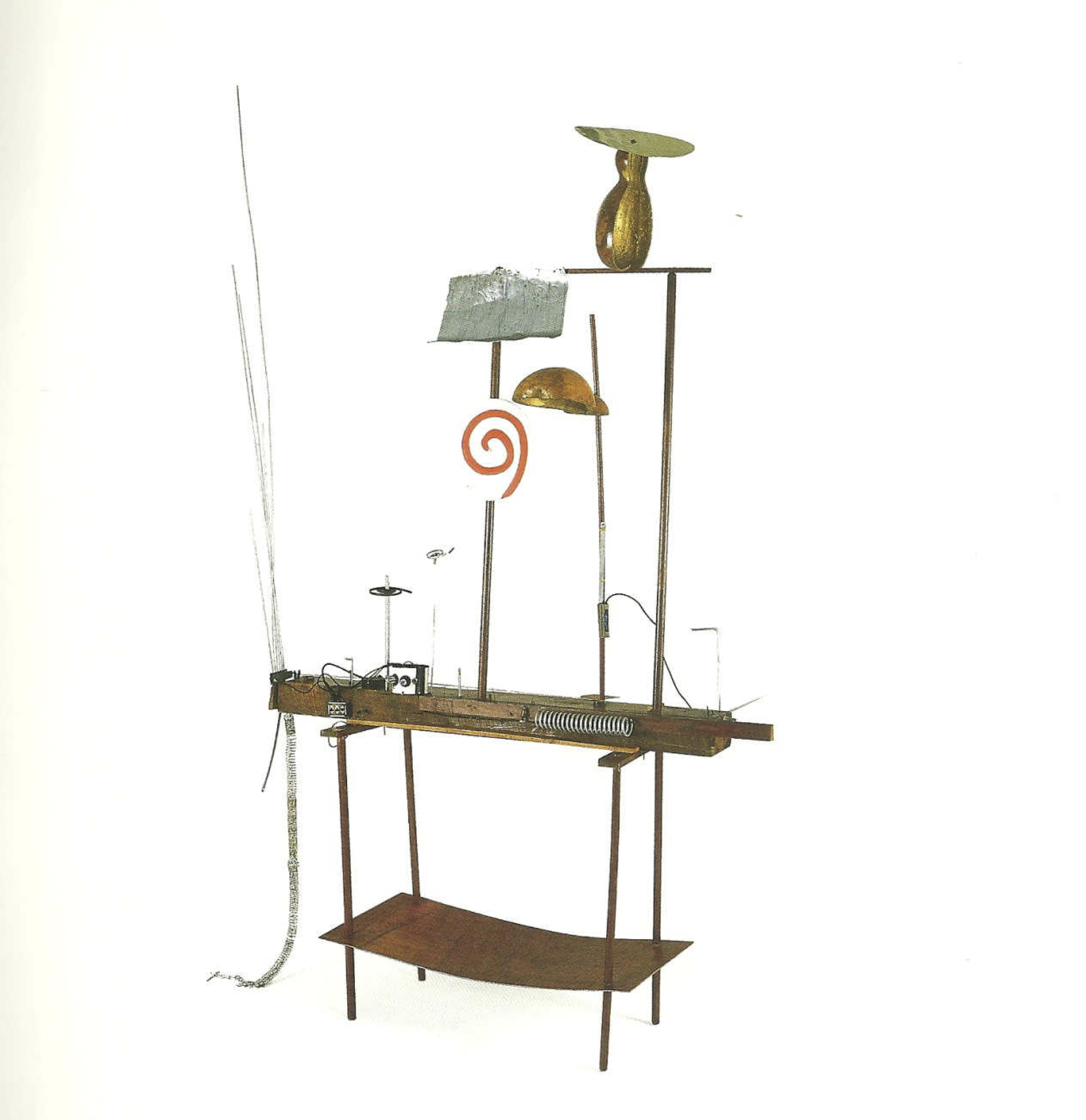

Several of Smetak’s instruments make gambiarra-like use of available materials. These include Piston Cretino (1976), comprising an aluminum kitchen funnel, plastic hose and piston nozzle, and the 1972 Bicho (figure 2), springs, gourds, wires, spirals, wooden cables and metal bars that are coupled to a wooden base with pickup that amplify the noises and friction of objects. There are kinetic instruments such as the 1971 Treis Sóis (wood, metal, Styrofoam and PVC pipe); collective instruments such as the 1973 Pindorama (a 2.2-meter-high wind instrument made of gourds, plastic tubes, bamboo, PVC pipe, wood and metal), and Bicéfalo (figure 3), two guitar arms intertwined over pieces of wood with two pickups attached; and plásticas sonoras such as Caosonância (1972), rectangular metal tray with stones surrounded by barbed wire, metal wire that holds several gourds forming an upward spiral around a long vertical bamboo rod that has on top a wind wheel.

Smetak’s work influenced other Brazilian musicians and sound artists – both those who had direct contact with him, including the tropicalist Gilberto Gil (figure 3), as well as those who didn’t, such as Tato Taborda (figure 4) and Vivian Caccuri (figure 5), among others.

In the early 2000s Brazilian artists were using the term gambiarra to describe bricolage, an objet trouvé, or a ready-made creative process that engaged different materials, media and artifacts. In sound art, Chelpa Ferro describes gambiarra instruments as "half adapted, constructed in a way … [and] the sound is also half limited, half raw,"18 while Paulo Nenflidio describes gambiarra as a process he used in creating his piece Polvo (2010) "to modify an original function of these materials,"19 Similarly, the sound art duo En Minus One (n-1) explain that “adapting, hacking, building, programming, improvising, pirating and appropriation were all part of” their process.20 More broadly, in the discourse of visual and media art it was pointed out that the interest in "establishing relations with a political and aesthetic accent" was a feature of Brazil’s technological culture.21

Inspired by Cage’s “Imaginary Landscape no. 4” (1951), Nenflidio created in 2006 Decabráquio Radiofônico (figure 6) which plays ten radios simultaneously. His 2003 work Berimbau Elétrico adapts traditional and nontraditional instruments to an electric context, while his Bicicleta Maracatu (2000) accommodates mechanisms of movement. In other pieces he has used gadgets such as electric razors and solenoids, or his own electromechanical mechanisms such as Lugares Sonoros: Teclado Decafônico Concreto (2005). Each key on this portable wooden keyboard activates an electromagnetic coil and wooden hammer connected by long cables to different points in the space—a steel beam, trash can, fire extinguisher, etc. The acoustic result derives from characteristics of the objects that are hit and of resonance of the space in which the system is installed.

Chelpa Ferro’s 2009 work Samba uses a table with a sewing machine on one side, a fishing reel on another and a snare drum in the middle (figure 7). The reel connects to the sewing machine through a fishing line stretched. When the machine is turned on, the line hits the snare drum, creating a rhythm similar to that of the samba. The result is a regular and un-regular rhythm with occasional faults, creating a noisy oscillation that adds to the sewing machine noise and spool gears picked up by microphones placed in each source (drum, reel, machine). "Samba is treacherous,” writes Caccuri about Chelpa Ferro’s work, “a machine that wants to have swing (ginga), a kind of gambiarra that wants to be precise."22 Here we see the gambioluthiery characteristics of assemblage, bricolage, trickery, sonorous visual installation, and the unstable procedural rhythm that juxtaposed mechanisms generate.

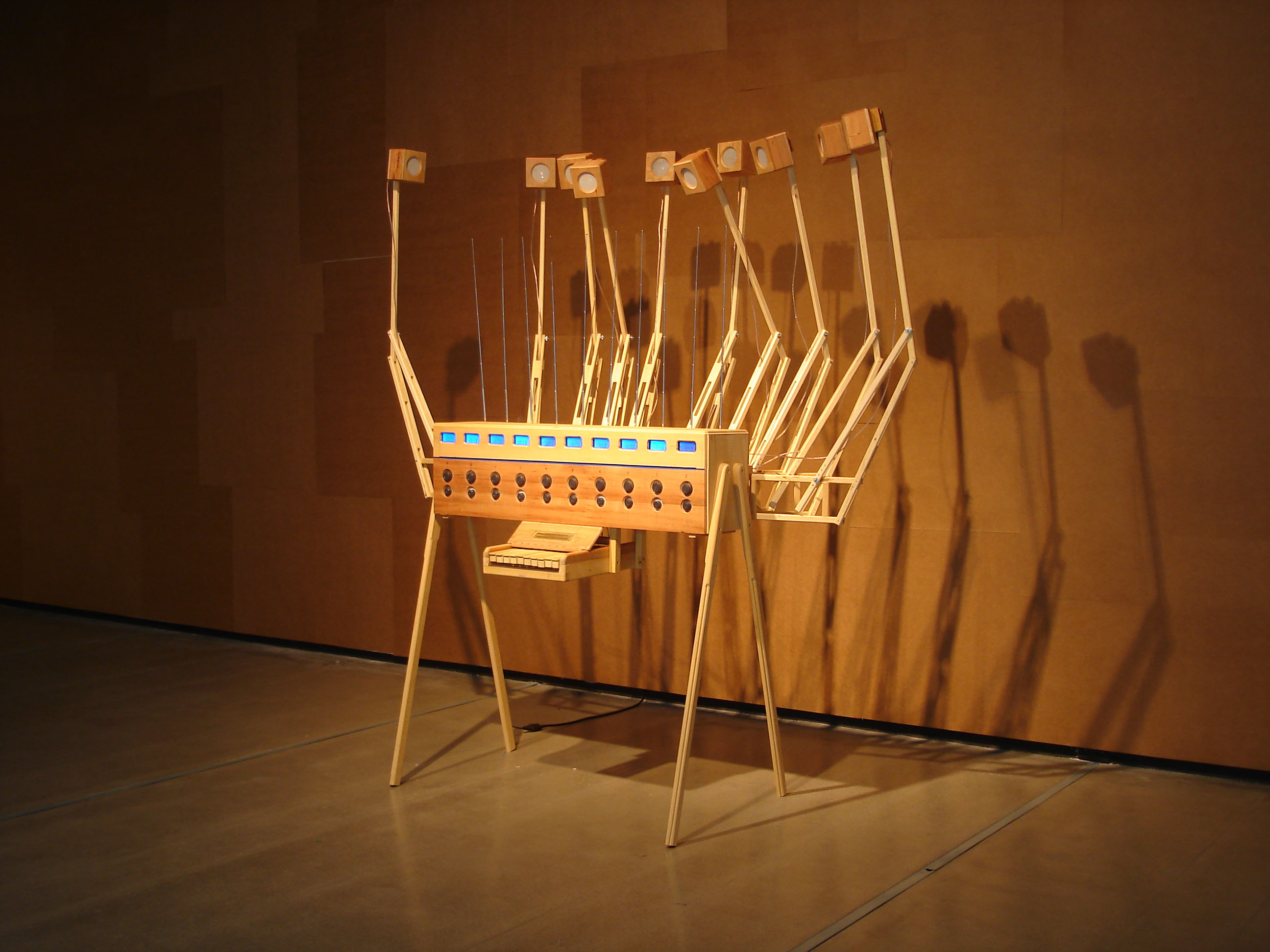

Another work that exemplifies gambioluthiery as an expanded sense of the musical instrument is Tato Taborda’s Geralda (1988-2001) (figure 4). A mix of multi-instrument and electroacoustic orchestra, Geralda is essentially a one-man-band instrument, where the player activates more than 70 sound sources using hands, elbows, knees, head and feet.23 Originally designed in 1992-1993, the instrument continued to evolve over the next decade as Taborda added sound layers and incorporated or abandoned materials and devices. It began with instruments and acoustic objects, to which he later added microphones (1998-1999) and live electronics (2001). "All the technology used in Geralda has a gambiarra way of being,” Tabora says. “It's rounded. It's technology without the edges."24 With its three species of sound — acoustic, electric and digital) — Geralda embodies one possible taxonomy of gambioluthiery.

Bio

Giuliano Obici is an artist, researcher and professor in the Art Department at Universidade Federal Fluminense. He holds degrees in music, communication and psychology, and is the author of the book Condiçao da Escuta (States of Listening).

http://www.giulianobici.com/

-

This chapter is a revision version of the author’s article “Gambioluthiery: Revisiting the Musical Instrument from a Bricolage Perspective,” Leonardo Music Journal 27 (2017), pp. 8792, and is based on his PhD dissertation, Gambiarra e experimentalismo sonoro. São Paulo: ECA-Universidade de São Paulo, Berlin: Technische Universität, 2014. ↩↩↩

-

See: Lisette Lagnado, “O malabarista e a gambiarra,” Revista Trópico, São Paulo 3 (2003); Ricardo Rosas, “The gambiarra: considerations on a recombinatory technology,” SESC - Caderno Video Brasil 2 (2005): 3653; Reed Ghazala. Circuit-Bending: Build your own alien instruments15 (John Wiley and Sons, 2005); Nicolas Collins, Handmade electronic music: the art of hardware hacking (Taylor & Francis, 2006); John Richards, “Getting the hands dirty,” Leonardo Music Journal 18 (2008): 2531; Caleb Kelly. Cracked media: the sound of malfunction. MIT Press, 2009; Erkki Huhtamo. Thinkering with Media: On the Art of Paul DeMarinis. In: Paul DeMarinis/Buried in Noise (Kehrer: 2010) (2011), pp. 3346; Kim Cascone. Residualism. In: Sound (Whitechapel: Documents of Contemporary Art (2011); Rodolfo Caesar. O loop como promessa de eternidade. In: Anais do XVIII ANPPOM. Salvador (Bahia). 2008, pp. 286-290. ↩↩↩↩↩

-

Antônio Houaiss. Dicionario Houaiss Online. Accessed 21 September 2019, 2018. ↩↩

-

Rodrigo Naumann Boueur. Fundamentos da gambiarra: a improvisação utilitária contemporânea e seu contexto socioeconômico. PhD thesis. Universidade de São Paulo, 2013. ↩

-

Ernesto Oroza. Desobediencia Tecnológica. De la revolucion al revolico. In: Recuperado de http://www.ernestooroza.com/desobediencia-tecnologica-de-la-revolucion-al-revolico (2012). ↩

-

Patricia Zavella, “Beyond the screams: Latino Punkeros contest nativist discourses,” Latin American Perspectives 39.2 (2012): 2741. ↩

-

With allusions to the historic practice of cannibalism by Brazilian aborigines, the anthropophagic movement proposed by the poet Oswald de Andrade in his Manifesto Antropófago (Cannibalist Manifesto) defended a plural culture that aimed to digest everything that comes from outside. See Oswald de Andrade, Manifesto Antropófago" Oswald Andrade. Manifesto Antropofágico. Em Piratininga ano 374 da deglutição do Bispo Sardinha. In: Revista de Antropofagia 1.1 (1928) Tropicalismo exposed the contradictions of modernity in Brazil: On the one hand, the capitalist development and strong urbanization of the 1950s and 1960s (including construction of the capital, Brasília) fueled Brazil's optimism; on the other hand, Brazil was still haunted by its position of underdevelopment and economic disadvantage in relation to Europe and North America: Flora Sussekind. Chorus, Contraries, Masses: The Tropicalist Experience and Brazil in the Late Sixties. In: Tropicália: A Revolution in Brazilian Culture (2005), pp. 31-58. ↩

-

These cultural aspects are discussed in Obici 1 and Rosas 2. ↩

-

M. Bakhtin. A cultura popular na Idade Média e no Renascimento. São Paulo/Brasília: Hucitec, 1987 [1977], p.10. ↩

-

Roberto DaMatta. Carnavais, Malandros e Heróis: para uma sociologia do dilema brasileiro. Rio de Janeiro: Zahar, 1979. ↩

-

In Dicionário Houaiss 3, carnivalization is described as "based on a mixture of diverse elements in which the rules or patterns (social, moral, ideological) commonly followed are subverted or set aside, in favor of stimuli, forms and contents more linked to instincts and senses, to the expansion of laughter and sensuality. Or 'condition of something that has such a mixture'" (my translation). The concept was invented by the Russian literary critic Mikhail Bakhtin (1895–1975). ↩

-

Paul DeMarinis. Buried in Noise. (Eds). Ingrid Beirer, Sabine Himmelsbach, and Carsten Seiarth. Berlin: Kehrer, 2010. ↩

-

Interview made with Tato Taborda, Berlin, 2013 (personal author records). ↩↩

-

Walter Smetak. Simbologia dos instrumentos. Salvador: Associação dos Amigos de W. Smetak, 2001 [1980]. ↩

-

According to Marco Scarassatti, "Plástica Sonora Silenciosa expands the field of music to the context of space and visuality. The sound is materialized in its own plastic form." See Marco Scarassatti, Walter Smetak: o alquimista dos sons (São Paulo: SESC-SP, 2008), 98. Douglas Kahn notes that artists utilized different terms such as radio art, audio art and sound art between 1970 and 1980. See Douglas Kahn, “Sound Art, Art, Music,” The Iowa Review Web 7.1 (2005): (accessed 9 September 2018). ↩

-

Franz Manata and Saulo Laurardes. Arte e Som no Brasil - Os primórdios. Ed. by Podcast 06 Chelpa Ferro. Online: podcast Arte Sonora. Mar. 20, 2017. url: http://exst.net/artesonora/podcasts/pod-06-chelpa-ferro/2013. ↩

-

Paulo Nenflido In. Fred Paulino. Gambiólogos: a gambiarra nos tempos digitais. Belo Horizonte: Kludgists, 2010, p.12. ↩

-

Giuliano Obici and Alexandre Fenerich. “Jardim das Gambiarras Chinesas: uma prática de montagem musical e bricolagem tecnológica,” Encontro Internacional de Música e Arte Sonora, Juiz de Fora-MG (2011). For more information about En Minus One (n-1), see http://n-1.art.br. ↩

-

Vivian Caccuri. Ouvindo as artes visuais: sonoridades de Waltercio Caldas, Cildo Meireles, Chelpa Ferro e Hélio Oiticica. MA thesis. Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, 2011, p.58. ↩

-

Geralda is similar to Acustica (1968-1970) and Zwei-Mann-Orchester (197173) by Mauricio Kagel (19312008), in which the instrumentation is a huge array of sound sources, a world of exotic instruments and almost surreal invention. ↩