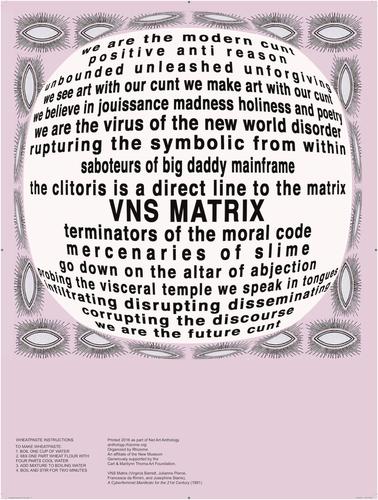

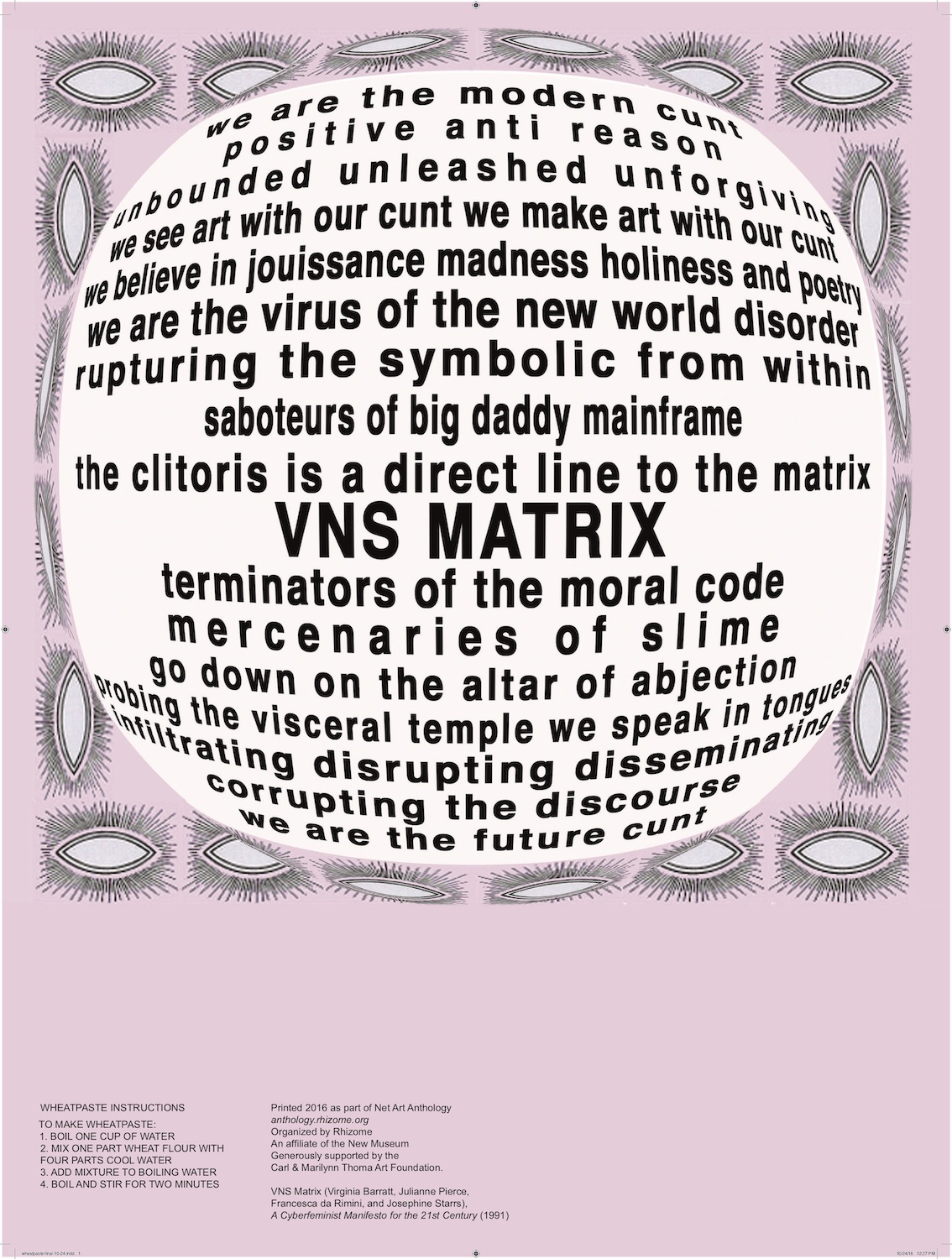

VNS Matrix Manifesto

They say that they foster disorder in all its forms. Confusion troubles violent debates disarray upsets disturbances incoherences irregularities divergences complications disagreements discords clashes polemics discussions contentions brawls disputes conflicts routs débâcles cataclysms disturbances quarrels agitation turbulence conflagrations chaos anarchy.

- Monique Wittig, 19711

I like to imagine that VNS Matrix’s A Cyberfeminist Manifesto for the 21st Century2 joyfully spat itself out. Simmered over summer under the thinning ozone in Adelaide – a city sited between the desert and the Antarctic; fed by the cyber fiction of Pat Cardigan, Octavia Butler, William Gibson, Neal Stephenson; simultaneously soothed and stimulated by techno, Patti Smith, ambient/trance and Diamanda Galas; enraged by the sexism of Wired and Mondo 2000; engaged by the raw psycho-sexuality of Kathy Acker and Linda Dement.

True to themselves, VNS Matrix have multiple origin stories. Perhaps they formed under the original name Velvet Down Under (VDU) to make afterhours porn for the Swedish market;3 or as an offshoot of the Australian Network for Art and Technology’s (ANAT) project to connect up women and artists to institutional computers and software. Alternatively, the Very Nice Sluts, Virtual Nodes of Slime or Vestibular Necronomic Strategists,4 could have arisen as a feminist fiction from MOOs, IRC squatter spaces, Madness activist groups, Fetish forums; or as fully formed quads born from the head of Zeus in Zoë Sofia’s Jupiter Space.5

An unexpected fusion in South Australia between military computing via British Nuclear tests and US Satellite surveillance, and a prospering cultural industry, fostered a new domain for experimental art. Feminists, artists and activists all, Julianne Pierce and Josephine Stars were immersed in postgraduate studies when they hooked up with Francesca da Rimini and Virginia Barratt, who had both been Executive Officers of ANAT. I am certain they lulled themselves to sleep contemplating Helene Cixous’ Medusa, Luce Irigaray’s divinity and Julia Kristeva’s abjection; awoke to Wittig’s Le corps Lesbien and RE:Search’s ANGRY WOMEN; and breakfasted on the Anarcho/Surrealist/Insurrectionary/Feminist (AS IF) Collective’s call to ‘fight with poetry and guns.’6

Having lived through this era (albeit in a distant city) I know it is impossible to unwrite the past three decades – to convey a pre-networked world where online space is foreign and/or dangerous; and to put the true impact of the Cyberfeminist Manifesto into perspective. However, I will try. Susan Sontag and others saw the mass transmission of HIV/AIDS as a marking point of the end of modernism, the rise of neo-conservatism and its denial of the flesh. The proliferation of the personal computer in the 1980s and the tentative networks of what was to become cyberspace were hyped as transcendent pinnacles of enlightenment philosophy – a disembodied utopia where ‘man’ could engage in the exchange of pure thoughts in a global arena of equality.

Sherry Turkle’s research reported that girls were enculturated to think of computer relations as antisocial ‘obsessive’ and ‘sad’.7 PCs became boys’ toys and the number of women studying computer science declined. Ada Lovelace and Grace Hooper were yet to be remediated and women’s role was primarily to reproduce and nurture via computer assembly or data input – a commodity in the informatics economy. Zoë Sofia warned us to carefully consider computing’s gendered politics as the woman/machine interface had historically slipped between a virgin/whore dichotomy.8

Ultimately the useful question was: ‘how important is computer technology in a feminist future?’

In 1967 Valerie Jean Solanas’ SCUM Manifesto argued that men had ruined the world, and that it was up to women to fix it. Her call to arms for ‘civic-minded, responsible, thrill-seeking females only to overthrow the government, eliminate the money system, institute complete automation and eliminate the male sex.’9 Solanas set the scene for radical feminism to embrace the machine in a utopia of automation without men. While she didn’t succeed in killing Andy Warhol, her manifest found many new readers.

Two decades later,10 Donna Haraway’s ‘argument for pleasure’ A Manifesto for Cyborgs was published. Haraway sought an alternate vision to negotiate the chasm between restrictive historical biological classification and a reconstituted contemporary erotic politics of embodiment. Her self-replicating fleshy-machine hybrid cyborg imagery was perfect – unfaithful to its patriarchal parentage and ‘committed to partiality, irony, intimacy and perversity’.11

The world wide web went live in August 1991 and A Cyberfeminist Manifesto for the 21st Century was first declared by VNS Matrix in Adelaide & Sydney, Australia. Although designed for the electronic networks it also circulated through traditional medias such as radio, fax, television, pasted in public spaces and in magazines as print ads.12

In 1992 it was distributed and exhibited at Cy MishMash World in Melbourne’s Elaine Gallery, but really hit the street as a 6m x 3m Billboard for the Watch This Space Public Art billboard project at the Tin Sheds Gallery, on a major arterial road beside the University of Sydney. Although Sage’s Encyclopaedia of New Media erroneously claim that Cyberfeminism is a term coined by Sadie Plant in 1994,13 VNS Matrix acknowledge it as co-creation in the cultural matrix of the early 1990s – a simultaneous unfolding between themselves, Plant at Warwick University in the UK, and an article on cyberfeminism posted to EchoNYC (an Internet bulletin board community) by Canadian Nancy Paterson.

Both exhilarating and shocking, Plant described the Manifesto as ‘the most stunning and dramatic’ manifestation of cyberfeminism.14 Much was written at the time, perhaps best exemplified by Jyanni Steffenson’s examination of the Manifesto’s mobilisation of slime and metaphors of flow, penetration and cutting up, ‘appropriating Irigaray and re-writing Kristeva’s theories of abjection’.15 Today bytes such as the clitoris is a direct line to the matrix and we make art with our cunt are woven into the genesis of internet culture. So much so that the Manifesto ‘authored in a mode that spoke to the conditions of early network culture: collaborative, plagiaristic, possibly drug-fueled, and pornographic’16 opened Rhizome’s definitive survey Net Art Anthology.

The Manifesto continued to propagate, translate and extrude around the networks, reaching a peak, according to Zoë Sofoulis, around 1996 in Australia.17 However, dialogues and exhibitions on the subject of cyberfeminism continued internationally, taking on a more critical and decentred approach, acknowledging women’s real-world conditions across the globe. Cornelia Sollfrank’s paper on female hackers for the New Cyberfeminist International in 1999 reported ‘My clitoris does not have a direct line to the Matrix—unfortunately. Such rhetoric mystifies technology and misrepresents the daily life of the female computer worker.’18

VNS Matrix were very aware of its place in the growing plurality of constant connections, overstimulation and losing touch. As Barratt reflects:

Cyberfeminism circa 1991 had glaring insufficiencies. The first ramraid on technology’s sanctified halls was a gender war, paying little heed to the political economy of technological production and consumption… But that first action, with all its insufficiencies, smashed the field wide open and these gaps provided pivot points towards a more intersectional cyberfeminism.19

Employed as artistic method and political strategy, Sollfrank later comments ‘their poetic emissions from and about the female body are always accompanied by a wink and a nudge.’20 This particularly Australian sense of humour and the Manifesto’s longevity have propelled it more recently to reach escape velocity. In 2014 sample-based collective Soda Jerk produced a video for Forever Now,21 a project documenting our times on a gold record and transmission launched into deep space. Undaddy Mainframe,22 their recombinant version of A Cyberfeminist Manifesto for the 21st Century is forever available for the viewing pleasure of a galactic audience.

The poesies of cyberfeminism, the progeny of industry & capital with socialist, continental and radical feminisms, is in the disruption of language. Dominatrices Wittig and Solanas, social theorists Haraway and Sofoulis, philosophers Irigaray and Kristeva, artists Dement and VNS Matrix, et al., fissured, fragmented, ruptured, holed, looped, unfurled, engorged, conceived and induced woman’s identity. Through powerful intent – for pleasure, in humour; with word and code, the modern cunt breached the sanitised fabric of the future.

Smeared with slime, they smiled.

Originally published on vnsmatrix.net. Courtesy of Melinda Rackham and VNS Matrix.

Bio

VNS Matrix was an artist collective founded in Adelaide, Australia, in 1991, by Josephine Starrs, Julianne Pierce, Francesca da Rimini and Virginia Barratt. Their work included installations, events, and posters distributed through the Internet, magazines, and billboards. Taking their point of departure in a sexualised and socially provocative relationship between women and technology the works subversively questioned discourses of domination and control in the expanding cyber space.

Melinda Rackham was an early Australian artist, curator and writer working in net.art and virtual reality, and founder of the global discussion platform -empyre-. Today her texts critique the worlds of art, artists, feminisms, ecosystems and social justice; and her latest book CoUNTess: Spoiling Illusions since 2008 (co-authored with Elvis Richardson) exposes the artworld's embedded gender asymmetry.

-

Monique Wittig, Les Guérillères (Viking Press, 1971) ↩

-

VNS Matrix, “Cyberfeminist Manifesto for the 21st Century“ ↩

-

Evelyn Wang, “The Cyberfeminists Who Called Themselves ‘the Future Cunt’,” DAZED (2016), http://www.dazeddigital.com/artsandculture/article/33703/1/cyberfeminist-manifesto-technology-vns-matrix↑ ↩

-

Virginia Barratt and Francesca da Rimini, “Hexing the Alien,” in CYBORG: Hacktivists, Freaks and Hybrid Uprisings (Berlin: Disruption Network Lab, 2015) ↩

-

Zoë Sophia (Sofoulis), “Virtual Corporeality: A Feminist View,” Australian Feminist Studies 15, no. Autumn 1992 (1992) ↩

-

Anarcho/Surrealist/Insurrectionary/Feminist Collective, “Anarcho-Surrealist-Insurrectionary-Feminist (as If) Manifesto,” http://www.takver.com/history/aia/aia00032.htm ↩

-

Sherry Turkle, “Computational Reticence: Why Women Fear the Intimate Machine,” in Technology and Women’s Voices, ed. C Kramarae (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1988). p46-47 ↩

-

Sofia 1995 Zoë Sophia (Sofoulis), “Of Spanners and Cyborgs: De-Homogenising Feminist Thinking on Technology,” in Transitions: New Australian Feminisms, ed. B Caine and R Pringle (Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 1995). p161 ↩

-

Valerie Solanas, “Scum Manifesto,” http://www.ccs.neu.edu/home/shivers/rants/scum.html ↩

-

Published in the US in Socialist Review 1985, and in Australian Feminist Studies in 1987 ↩

-

Donna J. Haraway, “A Manifesto for Cyborgs: Science, Technology, and Socialist Feminism in the 1980s,” Socialist Review 15, no. 2 (1985). p68 ↩

-

Kay Schaffer, “The Game Girls of VNS Matrix: Challenging Gendered Identities in Cyberspace,” in Virtual Gender: Fantasies of Subjectivity and Embodiment ed. Anne O’Farrell and Lynne Vallone (Michigan: University of Michigan Press, 1999) ↩

-

Mia Consalvo, “Cyberfeminism.” Encyclopedia of New Media. Ed. Steve Jones (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2002) p 109-10 ↩

-

Sadie Plant, “On the Matrix: Cyberfeminist Simulations,” in The Cybercultures Reader, ed. David Bell and Barbara M. Kennedy (London: Routledge, 2000) ↩

-

Jyanni Steffensen, “Slimy Metaphors for Technology: ‘The Clitoris Is a Direct Line to the Matrix'” in Discipline and Deviance: Technology, Gender, Machines (Duke University, Durham, North Carolina 1998) ↩

-

Rhizome and VNS Matrix, “A Cyberfeminist Manifesto for the 21st Century,” (2017), https://anthology.rhizome.org/a-cyber-feminist-manifesto-for-the-21st-century ↩

-

Zoë Sofoulis, “Cyberquake: Haraway’s Manifesto,” in Prefiguring Cyberculture: An Intellectual History, ed. D. Tofts, A. Jonson, and A. Cavallaro (MIT Press, 2002) ↩

-

Cornelia Sollfrank, “Women Hackers” (paper presented at the Next Cyberfeminsit International, Rotterdam, March 1999) ↩

-

Virginia Barratt, “From C to X: Networked Feminisms,” paper presented at Ars Electronica (Linz, Austria 2017) ↩

-

Cornelia Sollfrank, “The Truth About Cyberfeminism,” (2001), https://www.obn.org/reading_room/writings/html/truth.html ↩

-

Soda Jerk, Undaddy Mainframe, Digital video, 1:19 minutes (2014), http://www.sodajerk.com.au/video_work.php?v=20140724231348 ↩