Inclusive music footpaths: Os Heróis Indianos Romanos Africanos

Introduction

Os Heróis Indianos Romanos Africanos is a singular inclusive musical collective from Barreiro (Portugal) which has been performing for audiences since its debut in 2016. The group is, in fact, the result of an ongoing workshop proposed by OUT.RA – organizers of the renowned music festival OUT.FEST – in partnership with Associação NÓS, a nonprofit association also from Barreiro which is dedicated to social inclusion. That means it’s a project with a focus on people with so-called “disabilities” or those at risk of social disadvantage or exclusion, trying to use music as a tool for empowerment. This article is not only a brief summary of the activities made by the group but also an opportunity to reflect on the problems and potentials of music applied to social inclusion.

But before continuing to talk about the group, I'm going to say a few words so that you can better understand the context that led me to work with them. I’ve been working in Argentina in the field of music and so-called “disabilities” since we started in 1993 with Reynols, the band we still have there with a talented musician with Down Syndrome called Miguel Tomasín. Due to the group's growing visibility, and following the interest of various institutions that realized the importance of expanding inclusivity in music and the relative scarcity of projects in this area, I received some proposals to coordinate workshops in different countries. Most of these workshops ended with diverse inclusive concerts and activities with projects in various countries such as: Mumbly Wolfs (England), Les Harry’s (France), DNA? AND? (Norway), Ampliflied Elephants (Australia), Electroability Stavanger (Norway), Daddy Antogna y los de Helio (Argentina), Deep Fusion Butterfly (Greece), Les Knackiss (France), Le Group de la Mer du Nord (Belgium), Bergen Superorkester (Norway), Ateliers 18 Malakoff (France), Le Vecteur (Belgium), Capacitors (France), Creahm (Belgium), Les Turbulents (France), Pyramid of Arts (England), etc.

Music that breaks barriers

Going back to Os Heróis Indianos Romanos Africanos, the project started back in 2016 and its first year was, in fact, a pretty big challenge. Invited by OUT.RA, I arrived in Barreiro without previously knowing the group. We are talking about a big group with more than twenty people of different ages and with various “disabilities” and we had only one week to work out something and deliver a public concert. Luckily I had the help of local musicians Bá Alvares and André Neves. So we worked hard on that first 5-day-workshop at Associação NÓS. We mainly focused on exploring different inclusive techniques ranging from guided improvisation to electronic music, from adapted conduction to vocal exploration, from free-rock to sound poetry and so on. The group participated very actively in all the proposals and all together we prepared a nice setlist for the show. The concert was a memorable sold-out event at Velvet Be Jazz Club under the provisory name of “We2.” The audience was mostly made up of relatives and friends and a few music lovers intrigued by the novelty of the project.

The group loved the experience so much that they unanimously requested to continue with the activities as soon as possible. So we had a virtual meeting with OUT.RA and NÓS and decided to come back to work in 2017 to keep exploring the artistic potentials of all the participants.The second year was also very intense and it was good to see the group was growing in number with the arrival of new members eager to participate. We also had five days in a row for the workshop to try out some other techniques such as games through sound, alternative music notations, instrumental adaptations, improvisation, etc. On the weekend we ended with an intense show in a bigger venue: the stage of Associação Desenvolvimento Artes e Oficios (ADAO). The audience also increased and became more diverse compared to the previous show, showing that the community in general was interested in the project.

Then, due to various reasons, there was a break in the project. But the interest was still intact, so I traveled back to Barreiro in 2020 to continue the activities. That year we had another great weekly workshop with new members forming part of the group but something unexpected happened suddenly: at that precise moment the COVID-19 pandemic broke out. It was a big shock for everyone and we had to discuss options, finally it was clear that, for safety reasons and in order to avoid any contagion, a concert with an audience was not possible under those conditions. So we had to change the plan: the event planned at the local venue had to be cancelled and then it was decided to do the show as a live streaming performance to be broadcasted over the internet only. For this online-only show they group appeared using their actual name for the first time: Os Heróis Indianos Romanos Africanos, which was chosen previously by one of their members. The concert had a pretty good live audience and the video is still available online.

The COVID-19 pandemic generated undeniable global changes and, in our case, forced another pause. But the interest in the group had not gone away, so in early 2023 we returned to continue working with the group this time with the valuable additional contribution of local musician Leonardo Bindilatti. We had an enjoyable workshop at NÓS preparing new repertoire created by the group. And, as always, we ended the weekly workshop by playing a pretty intense concert, for the first time at the Barreiro Municipal Library (Biblioteca Municipal do Barreiro). The audience that filled the auditorium was very receptive and enthusiastic, and they were not only friends and family of the musicians but also music-loving audiences who normally attend concerts organized by OUT.RA and a few people who came especially from Lisbon for this event.

In February 2024 we had the mission to prepare a special show and we worked pretty hard during the workshop to get something new. The idea was to have a common thread between all the songs of the concert, so we chose the theme of “travel” to give a particular personality to each track: in fact, each song ended up having a particular geographical destination. We also used the voice of a presenter to announce each track and describe some of its particularities. All this was decided and worked together with the participants of the group. We had a first presentation of this show at the City Library, where the group also added costumes and some theatrical elements to increase the stage presence of the participants

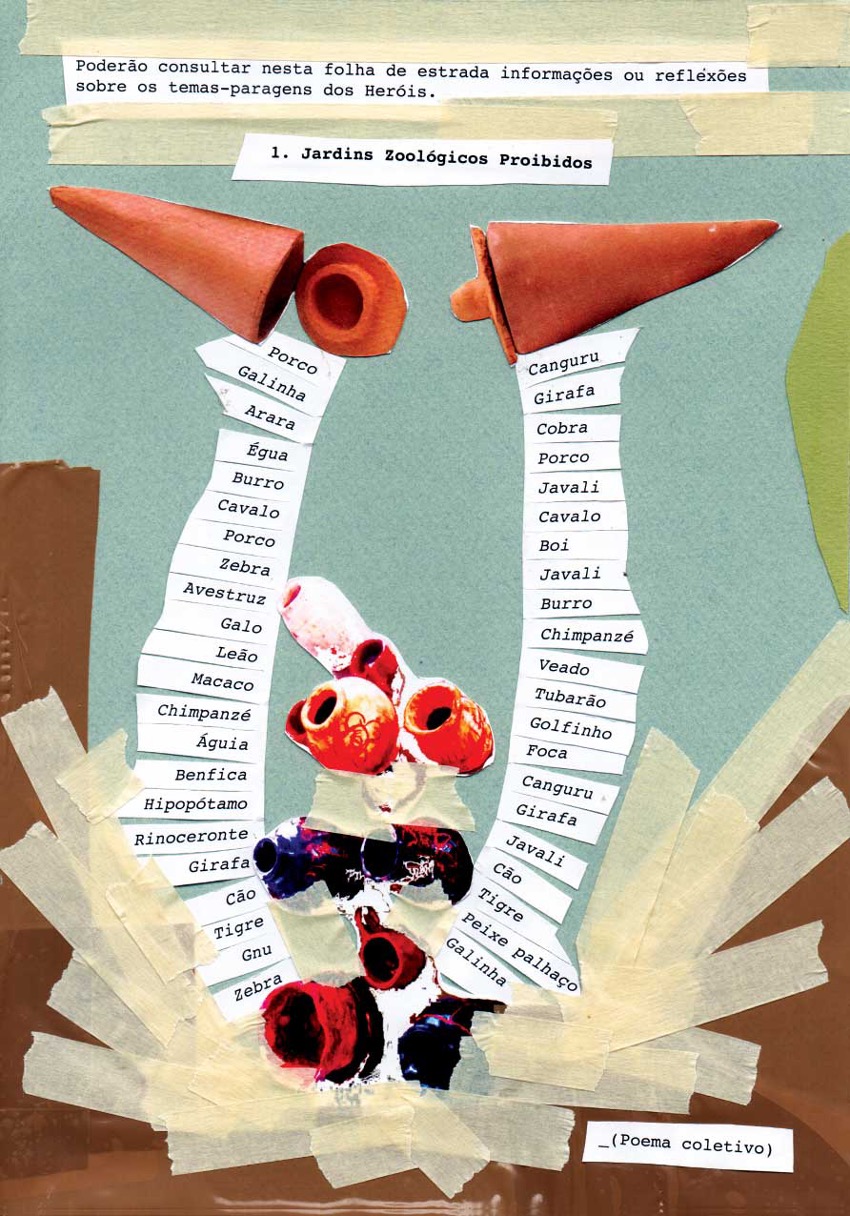

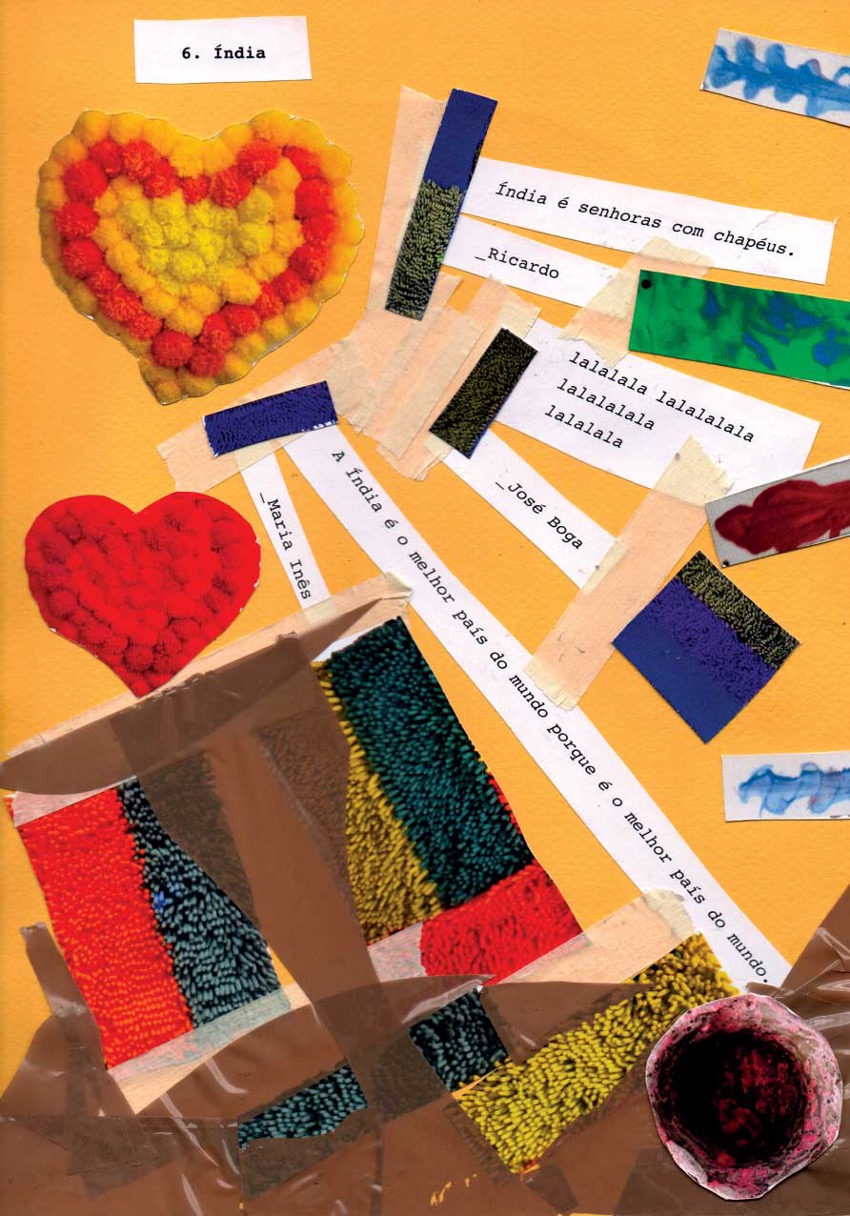

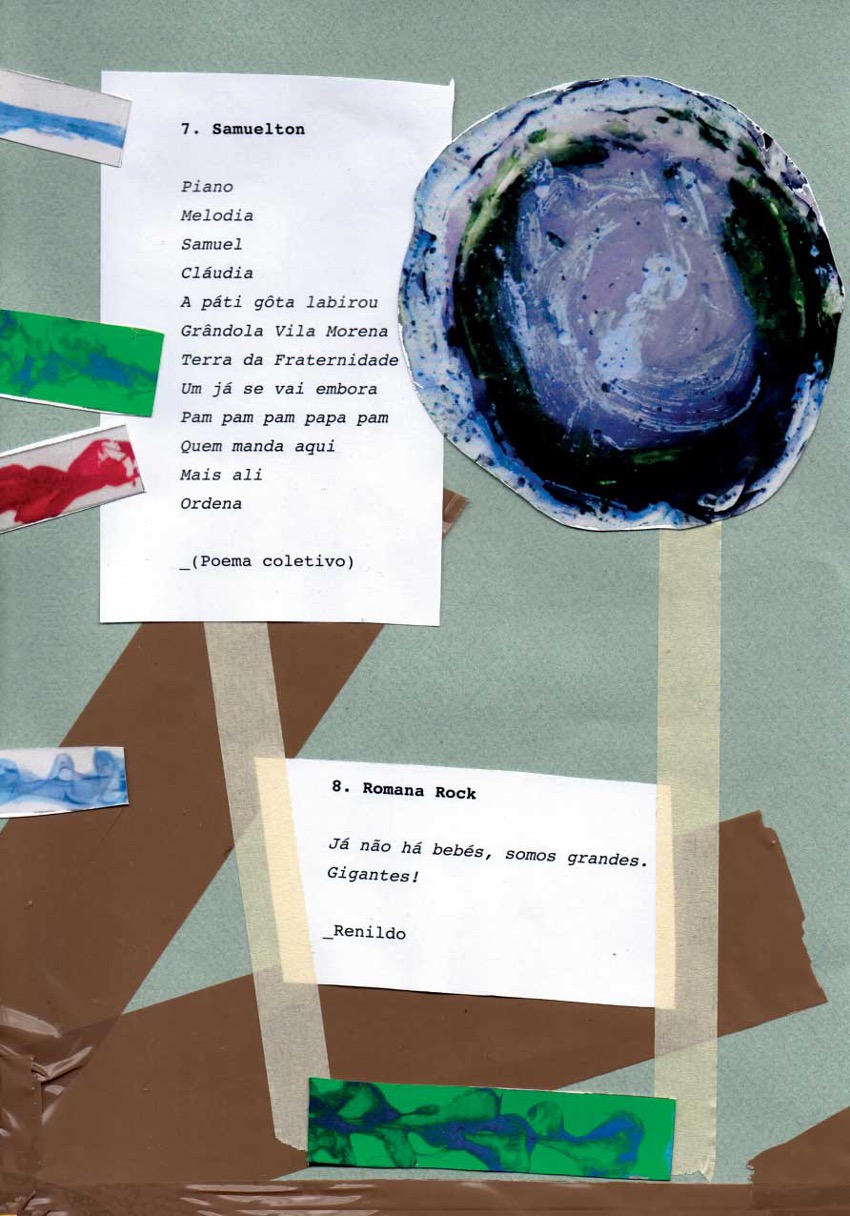

The concert worked pretty well but then we got our biggest challenge yet: to prepare the group to bring this previous show to the city’s biggest auditorium, Auditório Municipal Augusto Cabrita (AMAC). This was scheduled for October, opening the 2024 edition of OUT.FEST, Barreiro’s international music festival and one of the most important for experimental music in Portugal. Everyone agreed to continue working on the setlist we previously had but adding video, costumes and also creating a small publication with drawings and texts from all the participants to use as program of the show. This spectacle was finally called “A Viagem d’Os Heróis Indianos Romanos Africanos.”

Some scans of the publication:

After some work days at NÓS and a full rehearsal with lights and video at AMAC, the group was ready to go. With twenty-five artists onstage in full shape, it was a unique opportunity to perform before a larger audience and the group did not waste it. On the contrary: Os Heróis gave an epic show that was even reviewed by several articles from the local press. Here’s a translated quote of one of them:

“Those who had the privilege of attending the concert will certainly keep these moments in their memory, marked by the purity of sounds, the tenderness of smiles, an exploratory, sublime journey, which touched the rhythms of spirituality and the beauty of humanism.” (Rostos.pt 03/10/2024)

Finally, in 2025 we came back to work for a new season. The idea this time was to prepare and present a show of the group outside Barreiro. So the band crossed the Tagus River to perform in an historical venue: Sociedade Musical União Paredense (SMUP), an old concert house which has been organizing shows since 1899 in Parede, a small town located 20 km west of Lisbon. The concert was well-received by the audience, which included many new people seeing the group for the first time.

This has been a brief account of the activities carried out with Os Heróis since its inception. Now it's time to use this work to propose some reflections that address various relevant areas.

Music as a right, right?

Why are these kinds of open music projects truly important? First, I would like to bring attention to the inclusion of people with “disabilities”, focusing on music as a specific but no less important aspect. In fact, music inclusion involves many issues and should comprise many aspects, namely: music education, music development, music practice, music creation, recording and live performance, etc. In this sense, it is important to cover all the necessary facets required in each case to make them accessible for people with different “disabilities”, which of course always involves some kind of challenge.

Although it is not obvious, it is possible to adopt a perspective that conceives of music practice as a right of people with “disabilities.” Of course, this is not something that can be left only to people with disabilities, in fact this is actually supposed to be supported by society at large.

But what is the basis for saying that music can be considered a right in the field of disability? Well, we can refer to various sources that provide us with an adequate legal framework to demonstrate that this is a valid argument. For instance in its Article 30, the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (2006) proclaims that: “States Parties shall take appropriate measures to enable persons with disabilities to have the opportunity to develop and utilize their creative, artistic and intellectual potential, not only for their own benefit, but also for the enrichment of society.” In various countries, international treaties have the same legal hierarchy as the Constitution, so it is clearly something of importance.

On the other hand, it is worth remarking that the UN Convention states that art made by people with “disability” is not only intended for their exclusive benefit but also “for the enrichment of society.” A quick, incomplete list of international musicians with “disabilities” of all kinds may shed light on the meaning of this statement:

Ludwig van Beethoven, Wolfgang A. Mozart, Robert Schumann, Robert Wyatt, Cher, Stevie Wonder, Jaco Pastorious, Ray Charles, Django Reinhardt, Lisa Lysaker, Art Tatum, Roland Kirk, Syd Barret, Blind Lemon Jefferson, Monika Kuszynska, Blind Willie McTell, Chrissie Cochrane, Blind Willie Johnson, Blind Boy Fuller, Molly Joyce, Sonny Terry, Bredrich Smetana, Hank Williams, George Shearing, Skip Spence, José Feliciano, Anne Lighton, Joaquín Rodrigo, Viktoria Modesta, Pete Townsend, Maria Mucaria, Paul Stanley, Rick Allen, Lennie Tristano, Neesa Sunar, George Martin, Tony Iommi, Les Paul, Hua Yanjun, Jacqueline du Pré, Itzhak Perlman, Charlie Haden, Tabi, Neil Young, Ian Dury, John Kay, Michel Petrucciani, Precious Perez, Bill Withers, Eliza Hull, Jeff Healey, Joey Ramone, Lizzie Hosking, Brian Wilson, Lachi, Gabriela Frank, Agathe Backer Grøndahl, Haru Kobayashi, Rachel Goswell, Olga Gutiérrez, Mariko Takamura, Nomy Lamm, Ayumi Hamasaki, Nico, Edgard Winter, Yuliya Samoylova, Marika Gombitová, Evelyn Glennie, Ian Curtis, Lou Reed, Thelonious Monk, Lisa Sniderman, Charlie Parker, Gaelynn Lea and many, many more artists.

Also we should take in consideration the United Nations’ Report on the World Social Situation since they mention: “the process of improving the terms for individuals and groups to take part in society (Report on the World Social Situation, 2016, p. 17)." Music can be an important aspect for improving these terms in expressive and creative ways and the experience with Os Heróis Indianos Romanos Africanos in Barreiro shows the potential of these inclusive musical projects in helping to ensure those rights can be exercised effectively.

Finally, in 2015 the UN proclaimed the concept of “Universal Accessibility” creating also a symbol for it: It’s a universal human figure with open arms symbolizing inclusion for people at all levels. So then, taking this point in consideration, the question would be: How can we guarantee universal access to music to all those who want to access it, regardless of their condition?

Techniques and approaches for inclusion

Let’s start this section quoting Lennard J. Davis: “the ‘problem’ is not the person with disabilities; the problem is the way that normalcy is constructed to create the ‘problem’ of the disabled person.” If we follow this reasoning, the responsibility would not fall on people with “disabilities” but on society as a whole.

Likewise, going from the general to the particular, the effects of the social construction of normalcy can also be traced in the field of music. For instance, it's important to keep in mind that the traditional music pedagogy approach is insufficient to guarantee universal accessibility to music for the vast majority of people with “disabilities.” But why is this so? First, let's keep in mind that musical instruments were mostly designed for a "standard" corporeality following the “normalcy” patterns. Now, what about corporealities that deviate from the norm? In these cases, traditional musical pedagogy does not seem to have many solutions to offer, but fortunately, there are other approaches and techniques that can be useful for generating new paradigms.

Here, both specific instrumental adaptations and the use of new technologies are extremely useful in ensuring universal accessibility for people with all types of disabilities. Let's not lose sight of the fact that since the second half of the 20th century there has been a multiplication of sound sources used in musical practice, which in our case can be very useful. Until the 19th century western music was focused on the voice and traditional musical instruments (chordophones, aerophones, membranophones and idiophones). But from the 20th century onwards, new technologic sources emerged: sound recording, electronic instruments, sound processing, virtual/digital Instruments, apps, etc.

All of these technologies provide more flexible options that can be adapted to each person's needs, covering a wide range of corporealities and cognitive abilities. That’s why they are important tools to ensure accessibility. At the same time, there has also been a diversification of the music possibilities which includes very different practices as: instrumental & vocal music, electroacoustic & electronic music, aleatory & atonal music, microtonal music, improvised music, self invented instruments, field recordings, sound art, noise, etc.

Ensuring the participation of people with different mental/physical abilities implies embracing full body diversity and being open to work with other cognition standards. This wide diversity helps us to work with an inclusive conception of music, whose main purpose is to include people through musical practice despite all “disabilities” – and also to generate spaces where this musical inclusion can truly take place effectively. But in the same way that musical instruments were created for a "standard" corporeality, traditional pedagogy also presents problems in guaranteeing accessibility, especially for people with different forms of cognitive “disability.” That's why it's important to be able to incorporate other, more flexible techniques and approaches like: guided improvisation, alternative forms of notation, collective composition, freeform vocal exploration, research and application of new devices and technologies for inclusion, etc. This broad offering counters the limitations of traditional music pedagogy and offers us many forms of activity that serve to expand and enrich inclusive possibilities.

But techniques and resources aren’t enough – it’s also necessary, and extremely important, to create safe spaces where each participant's playing is fully heard and respected. What these spaces should never forget to preserve is playfulness. Playfulness is fundamental and could be defined as the necessary propensity to connect – or to reconnect – with the world of play, which every human being possesses to some extent. Also, having a wide margin of freedom and flexibility to organize activities is essential to guarantee the quality of the process, keeping in mind that when working with people with disabilities the specific characteristics of the group will undoubtedly influence the work being done. Likewise, we'll have to adapt to the specific possibilities offered, trying to match them as closely as possible to the capabilities of the participants.

Social Perspective

The social aspect provides a different perspective, which forces us to rethink the place of music. In this sense, it is pertinent to emphasize that music generates bonds that transcend verbal language and foster group interaction, which is also a stimulus for inclusion. But we must not forget that historically, for many years, people with disabilities have been treated as mere "objects," and even today – although it pains us – this continues to happen in many areas in our societies.

Therefore – and beyond any "medical diagnosis" – an important part of our work consists of restoring the person with a “disability” to their status as a "subject." This means, first and foremost, fully understanding them as persons, but also, as we already have seen, as "subjects of right." From this perspective, in our particular case, it is also about restoring the person with a “disability” to their role as an "artistic subject." Speaking of "subject" implies accepting that person's particularities and understanding that no one can express themselves for them but themselves. Then they are the ones who must be actively involved in this field, of course with the proper social support.

That being the case, the musician's place is a socializing place because it brings that expression to others, which creates bonds that help improve their quality of life and that of others. Since expression is finally the main source of any artistic practice, anything that would help people with “disabilities” to fully express themselves artistically should be valued for its potential contributions.

This kind of inclusive music project contributes to reintegrating the individual's status as a person with a “disability” because it opens up expression from a symbolic place that allows them to construct their own rules and, from there, share them with the entire community.

Then, of course, to guarantee accessibility to music, social support is needed. Not only economical support but also appreciation, interaction with the community to protect their rights and the access to music activities according to the abilities of each person. Maintaining a social perspective is always important because it makes us all, in one way or another, responsible for ensuring this accessibility. Universal Accessibility to Music, in fact, could be the main aim here.

Ethics and beyond

Every practice with social implications presupposes an ethical dimension, and music is by no means an exception. Since our inclusive projects work largely with improvisation, there’s a presupposition that what is being played is constantly emerging, so this implies that there is always some degree of uncertainty. Taking the risks of confronting what is not completely familiar constitutes one of the central ethical points in this regard. The British composer Cornelius Cardew referred precisely to these issues in his text “Toward an Ethics of Improvisation” (included in the Treatise Handbook) when, for example, he emphasized the difference "between making a sound and being a sound."

But the ethical dimension is also present in the coordination of music projects for people with disabilities. Listening to people with “disabilities” and providing them with opportunities to participate is a basic requirement on a human level. That’s why coordinators should be able to listen carefully to all the participants to offer them as broad an array of options as possible to integrate people from across the “disability spectrum” into the practice. When we say listening, we also mean listening closely to people who don't have full access to language or who have difficulties with it. Even without language, we can always find forms of communication through gestures and also through various forms of sound that allow them to express themselves. This is, in itself, a challenge, but without a doubt, the coordinators' willingness to carry this out is one of the aspects most exposed to ethical assessment.

On the other hand, the teaching role implies a dimension of power, so being aware of this is fundamental. The way a teacher or coordinator addresses the class and the students' parents must be also considered from an ethical perspective. Fully understanding that any negative words we say can profoundly affect others, considering the emotional implications for people with “disabilities” and their communities, should be enough to warrant extreme caution when making any value judgments in this type of context.

Future and conclusions

Going back to Os Heróis Indianos Romanos Africanos we can understand the importance of the project not only for themselves but for Barreiro and its community in general. To have a musical project like this opens new paths, bringing inclusive practices to a wider social visibility.

In any case and from a broader social perspective, this kind of project can also help to "de-problematize" people with “disabilities,” that is, to stop treating them merely as a "problem" and re-establish them as socially valued subjects. This means celebrating diversity and rediscovering the pleasure that every society should have in including each of its members. If people with “disabilities” have historically been ignored, hidden and even exterminated – it is time to collectively consider what role we want for them in our society.

Since “disability” is nothing but a social construction, it is our responsibility to actively work for more inclusive forms of collective interaction. Facilitating their access to a stage through musical expression is only one option, but a clearly inclusive one. Sound can reach many places where reason cannot, and perhaps that is why musical work with people with “disabilities” manages to overcome so many barriers.

But what can we expect from Os Heróis Indianos Romanos Africanos’ moving forward into the future? Well, the idea is to maintain the project's continuity and foster its growth as much as possible. Of course this will involve new challenges, such as organizing concerts in different locations, promoting them and possibly working on the release of an album documenting the group's output. We'll see where Os Heróis’ upcoming activities take us to, but we hope that at least they can inspire many more projects like this all around. Inclusive experiences should not be mere exceptions but something established in the context of the arts. Music is an invaluable tool to contribute to improving the lives of people with all types of “disabilities.” So let sound open the doors to a more inclusive world. We look forward to a future full of transformation for all people, regardless of whether they are Indians, Romans, or Africans.

BIO

Alan Courtis is a Buenos Aires-born experimental composer, musician and founder member of cult Argentinian group, Reynols. He has several hundred releases to his name as well as a dizzying array of collaborations with the likes of Pauline Oliveros, Lee Ranaldo, Jim O’Rourke, Merzbow, and Otomo Yoshihide. He has run inclusive music workshops in Europe, South America, USA, New Zealand & Japan.

Bibliography

Bernstein, B., Courtis, A. & Zimbaldo, A. (2019). Disonancias y Consonancias: Reflexiones sobre música, educación y discapacidad. Buenos Aires: Miño y Dávila Editores.

Cardew, Cornelius (1970) Treatise Handbook. London: Edition Peters.

Courtis, Alan (2021) “Music & Dis/Ability: Inclusive Perspectives in the Argentinian Context” in Figueroa, Chantal y Hernández-Saca, David I. (Eds.) Dis/ability in the Americas: The Intersections of Education, Power, and Identity (Education in Latin America and the Caribbean) London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Davis, L. J. (1995). Enforcing normalcy. Disability, deafness and the body. London/New York: Verso.

Reynols: Minecxiología (2022). Buenos Aires: Dobra Robota.

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UN). (2006).

Report on the World Social Situation. (2016). United Nations.