The Ableism of Music

“This is an all-hands-on-deck situation...everybody has to pull equal weight.”

* undisclosed length of pieces *

* expected silence for long durations without space for noise/bodily sounds *

These are sentiments and accounts of experiences I have had in music settings. I share these not to complain, not to bicker, and not to solely vent (although that can be helpful sometimes). Instead, I share these to highlight the ableist assumptions in music settings, which can be well-meaning and well-intentioned but poorly received, especially in live performance settings. And further, I share these to highlight the ableist assumptions to forward disability, the category, the experience, the idea that it is, as a legitimate minority and identity in music settings and overall.

Ableism is conventionally understood in academic contexts as a system of oppression, encompassing prejudicial attitudes, discriminatory behaviors, and systemic inequities, that devalues people with disabilities and privileges nondisabled norms. It is further defined by Hehir (2002) as the “devaluation of disability” and by Talila Lewis as a “system that places value on people’s bodies and minds based on societally constructed ideas of normalcy, intelligence, excellence, and productivity. These constructed ideas are deeply rooted in anti-Blackness, eugenics, colonialism, and capitalism” (Lewis, n.d.).

Ableism is something that can simultaneously be obvious and elusive, physical and visceral, and minor and major. It can be evident to those who experience it, daily or in long-term contexts, such as the continual perpetuation of attitudinal beliefs that disabled people should not be paid legal minimum wage, and how subminimum wage policies for people with disabilities are grounded in misconceptions about their abilities and contributions, reflecting discriminatory beliefs rather than objective productivity deficits (Bagenstos, 2003).

Yet it can be elusive; sometimes it’s something you are not really aware of until you are, such as the stares and comments and expressions experienced when joining disability flight boarding when you have an invisible disability (personal anecdote).

It can be physical, such as stairs instead of a ramp for wheelchair access, even in new architectural buildings and public art projects (Cusick, 2018), yet visceral at the same time, such as the exclusion of disabled people from many now long-lost DEI initiatives (Scheiber & Gelles, 2025).

Lastly, it can be minor, such as the assumption that disabled people need help and touching them, and significant, such as the systemic discrimination against disabled people, such as in the U.S. restriction on income for married individuals on social security benefits (Smilowitz, 2021).

Background

As a disabled composer and performer, I have been fascinated by how the concept and even the term of “disability” is perceived and received in music settings. Ultimately, many long-held concepts and assumptions about how music should be made, produced, and presented hold up many ableist underpinnings. I have an impaired left hand from a previous car accident. It took me a while to really come out as “disabled,” especially regarding making music and my artistry, even though when I look back at my artistic work leading up to that point, much of it was already alluding to recognizing and embracing the disability identity as a source of creativity. I think part of my hesitation in coming out was because of the fear, stigmatization, and fetishization of disability in the arts and music specifically.

For example, individuals have often approached me and/or my collaborators after my performances to say how “inspiring” what we are doing is, despite our disability, or how fascinating it is that we “overcame” our disability. While I respect that these individuals are often well-meaning, ultimately, these comments do not really get at the heart of what we are doing as disabled musicians. To me, they reflect the overwhelming distance that music has to go to make progress in terms of recognizing disability as a legitimate identity and experience to be explored in musical terms, rather than something that has to be overcome to get to a false, socially-constructed standard or normal, or something that one has to be inspired by. Would you say to a Black musician that it is so inspiring that they were able to perform while also being Black? Would you tell a female musician that it's great they overcame their gender to perform? These questions seem at odds when positioned in the context of other underrepresented identities in musical settings. Yet, these are questions that regularly come up with disabled artists and especially disabled musicians. Why can’t disability just be? Why does it always have to be moved away from or jumped over (overcome)? Why does it have to be inspiring?

Disability rights activist Stella Young frequently underscored this, stating that she longs to “live in a world where we don’t turn disabled people into objects of inspiration and pity and freak shows for non-disabled people to gawk at.” This emphasizes the harmful portrayal of disabled people as objects of fascination or pity rather than as individuals with total humanity and dignity, and again connects to the idea of the virtuoso as a sort of fantastical being (Young, 2014). This also intersects with the concept of “inspiration porn,” a term coined by Young (2014) in an attempt to describe the objectification of disabled people by nondisabled individuals, particularly by deeming them “inspirational” for everyday acts such as standing on the sidewalk or getting coffee.

Disability Culture at Odds with Music Culture

At the same time, as I have become more familiar with disability culture and disability arts, it has been fascinating how various things are valued that often seem contrarian to the norms and assumptions of the music industry, and how ultimately many long-held concepts and assumptions about how music should be made, produced, and presented hold many ableist underpinnings. In the following paragraphs, I will outline several key concepts of disability culture that are seemingly at odds with the assumed ways of making, producing, and presenting music.

Rest

Rest is a concept and experience fundamentally at odds with capitalist values of productivity and success. Engaging in rest can be an act of resistance and self-reclamation, a way to challenge where value and worth are located. Alison Kafer (2013) writes on rest in disability culture that it is not simply an individual act of self-care, but a collective political practice that resists ableist demands for constant productivity. Similarly, Sami Schalk (2018) frames rest not as a luxury, but as a survival strategy tied to joy and resistance. Disabled artists often reflect this in their work. For example, artist Finnegan Shannon’s ongoing series Do you want us here or not (2018-ongoing) highlights the lack of seating in museum settings by presenting a bench or similar object as a work of art in exhibition and gallery spaces. Dancer Jerron Herman’s work LAX (2023-ongoing) underscores the relationship between tension and relaxation in dance performance, resisting the temptations to perform, produce, and showcase (Herman, 2023). Both of these works foreground the body’s needs, specifically rest, as legitimate and integral.

However, in music settings, especially in concert set-ups and production, limited time for setup and soundcheck often necessitates acting quickly, leaving little room for rest and recognition of bodily needs. A prime example of this in concert settings is the expected silence for long durations without space for noise or bodily sounds, especially in classical music settings. At the start of many concerts and in concert programs, there is often a statement such as “please silence cell phones and refrain from coughing.” While these statements can foster a collective sense of attentive listening, they can also be harmful by failing to make space for necessary bodily and aural sounds, such as coughing. The expectation of silence in classical music spaces is not neutral; it reflects and reinforces ableist norms that demand bodies be controlled, quiet, and non-disruptive. Such expectations can marginalize individuals whose bodies produce sound—through coughing, movement, or assistive devices—by framing these natural and necessary expressions as inappropriate or unwelcome, rather than as integral to the shared experience (Kafer, 2013, p. 141).

Additionally, these concert norms are inherently inaccessible to families, especially those with young children. When I had my baby in the Fall of 2025, my husband and I wanted to take our child to as many events as possible and not isolate him from our lives. Yet even though it was highly likely that my son would be sleeping during these events, the chance that he might cry or make noise discouraged me from bringing him, as I didn’t want to disrupt the event and/or documentation/recording. At the same time, I realized that many visual arts events were inherently more accessible as a family. For example, a gallery opening has flexible hours, flexibility to move around, and little emphasis on silence. I know these are often not ideal for taking in art, but the option is there. I recognize the importance of audience silence and the communal experience that concert events offer. Yet, the inaccessibility for families and disabled people can be a substantial barrier that should be questioned. Why do families always need to be separated into family concerts? Why do those who “make noise” need to be separated from regular concert programming?

Time

Disability culture often questions normative assumptions about and expectations of time. A common concept in disability culture is that of “crip time,” which Kafer describes as bending “the clock to meet disabled bodies and minds” rather than bending “disabled bodies and minds to meet the clock.” “Crip time” takes after the disability terms “crip” and “cripple.” Both are commonly associated with disability and have historically been used in derogatory contexts to describe disabled individuals (Hutcheon & Wolbring, 2013). However, it has more recently been reclaimed in a positive light as a means to challenge prejudice, stereotypes, and ableist attitudes.

In concert music settings, it is always fascinating to me how, despite music being a temporal medium, elements of time are often left hidden or undisclosed. For example, on most concert programs, the length of pieces is usually not listed, and even the time expectations of the whole concert experience can sometimes be a mystery, including the duration of the entire program. I recognize that there are, of course, exceptions to this, and I have certainly been in scenarios where they list the timing of pieces on a program and the overall concert length. However, more often than not, that factor is missing. And as a disabled individual reckoning with physical needs on a day-to-day basis, I feel that it is helpful to know the expected duration and length of the concert you are at. Why do these always have to be a mystery? Why in music settings do we need to leave the factor of time, and especially remaining time, hidden?

Additionally, one of my favorite disabled musicians and artists, JJJJJerome Ellis, literally takes time at the beginning of his sets to provide a visual description of himself and the performance setting. I love this aspect of his performance. Instead of starting with music right away, he takes time to visually set up the performance space, which is especially helpful to blind and low-vision audiences. Again, he builds this time into the musical performance itself. Additionally, throughout his performances, he often introduces silences. He takes time between transitioning between pieces and instruments naturally and slowly, not rushing from one piece to the next or forcing quick transitions that are often expected in concert settings. Instead, he embraces “crip time,” not bending to the normative clock but bending the performance “clock” to meet his body and mind (Ellis, 2021).

Language

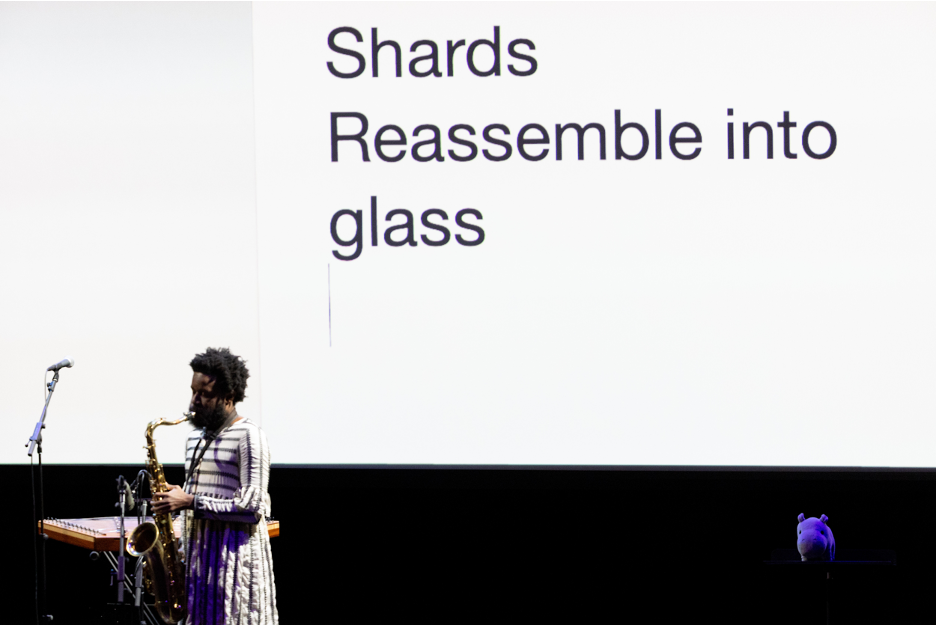

I have been on countless panels and in numerous settings that are focused on disability, yet omit the actual term “disability” from the title or talking points for the event. Example titles include “This Ability Roundtable” and “Differently Abled Panel,” and the image below was chosen for an accompanying reading list for an exhibition I co-curated that was entirely and openly about disability.

Why is there a need to skirt around the term “disability?" When compared to other underrepresented identities, would you present a panel on feminist politics on cross out the “fe” in “female?" Would you show a panel on Black identity in music and title it, “Different Shades of Whiteness?” As a disabled artist, while I understand these efforts are not entirely malicious, they are exhausting and continually erode efforts to raise disability as a legitimate and, in my opinion, significant experience and identity. And why can’t disability just be? Why does it always have to be altered or attempted to get back to a false sense of “normal”?

In music settings specifically, some of the hurdles here point to specific instruments in musical practice, as most musical instruments are made for particular abilities. Unlike dance and visual art, where the body is often seen as free of physical norms and restrictions, music has consistently been tied to instruments with specific physical expectations for performers, such as the violin, piano, or even vocal performance. I therefore believe this lends musical practice to attempting to skirt around the term of “disability,” because, especially in Western classical music canon, many instruments practiced in this canon prop up an idea of ability and specific ability and physicality, and experiencing disability in music contexts often means experiencing a loss, an inability to play one’s instruments or practice musically.

They also have real-world consequences. Disability is consistently one of the most under-recognized minorities, despite encompassing roughly 16% of the global population (Global Disability Inclusion Report, 2025), and by forwarding even the term “disability,” I believe that people will stop being afraid of even speaking the term. Thus, these efforts will trickle to social security, legal rights and representation, and so forth. When people ask me what term I am comfortable saying, I always recall a conversation with the legendary disability activist Judy Heumann, who was such a tireless mentor to so many people. Judy knew precisely when and how to progress your thinking, and in a conversation, once she was looking at my biography, she stated, “I don’t see ‘disability’ anywhere in your bio,” yet at the time and going forward, disability had been a huge crux of my work. This question stuck with me. Judy was trying to prioritize stating the term “disability” as much as possible, to encourage people not to be afraid of speaking it, and thus ultimately legitimizing it as an identity.

Help

In disability culture, the concept of help is often viewed with contention because traditional notions of assistance can reinforce power imbalances between disabled and non-disabled people. While support can be essential for access and participation, unsolicited or paternalistic help can undermine autonomy and agency, reflecting broader societal attitudes that frame disabled people as dependent rather than empowered actors (Kuppers, 2003; Garland-Thomson, 2005). For example, disability studies scholars emphasize that help should be collaborative and consent-based, aligning with principles of interdependence rather than charity, which historically positioned disabled individuals as passive recipients of aid (Charlton, 1998; Oliver, 1990). This tension highlights how “help” can both enable and constrain, depending on its framing and context.

I have been in several concert situations, specifically with setting up and breaking down equipment, where colleagues assume I need help because I am holding something differently due to my left hand. They will often run up and take the item from me, even though I am trying to help. Counterintuitively, there is an assumption that one should go above and beyond to assist beyond their physical limits with concert set-up and tear-down, especially in music production settings, even when it exceeds the legitimate need for assistive architecture like elevators.

For example, when I was hosting blind artist Andy Slater for an event, we were waiting for the elevator to go up to the performance space. As we were waiting, a fellow student came over with some equipment to bring up to the performance space, which was three stories up. Although we were first in line for the elevator, the student stated that we could not use it unless we were bringing equipment up. However, both Andy and I were physically preoccupied with helping him navigate to the actual performance space. Additionally, during a concert set-up one time, I was sitting down to rest because I had ongoing foot pain. A colleague asked why I was sitting down and not helping, and it really stood out to me that we cannot even trust one to assess their own rest and help capacities.

These experiences really struck a chord with the ableist underpinnings of these concert expectations and settings, as we drive ourselves towards unrealistic extremes in efforts to showcase music, yet defy physical, mental, and cognitive needs. Who has the right to help in music settings, and why do we assume that people cannot determine their own help needs? As stated in one of the first quotes in this article, I often see the phrases “This is an all-hands-on-deck situation...everybody has to pull equal weight,” yet can individuals assess their own capacity to help?

Virtuosity

And lastly, virtuosity. This is a dissertation research topic of mine, and I have written about it in other areas, such as through the work of disabled dancers Marc Brew and Kayla Hamilton (Joyce, 2023). Therefore, I won’t go into it in detail here; however, it is essential to mention it. Throughout the canon of Western classical music, virtuosity has been a highly valued status for performers to achieve. The concept is perhaps the most esteemed level of performance for a musician to attain across instruments and vocal types. When one compliments a performance as “virtuosic” or praises a performer as a “virtuoso,” they are typically offering their highest form of praise, often deemed as a God-like form of attainment, fulfillment, and ultimately desirement.

As a disabled composer and performer, I have wrestled with concepts of virtuosity that value complexity over simplicity, mobility over immobility, and ultimately ability over disability. When I began developing my practice as a performer, I questioned whether virtuosity was available to me. I seek to accommodate my disability in performance by using adaptive music technology and instruments. However, my left hand does not move particularly fast or in a manner that traditional virtuosity embraces, that of a visually impressive, almost Olympian-like form of physicality. Thus, normative virtuosity embraces ableist notions of ability and physicality, often reverting to ableist views of the body and music in performance.

Imaginaries

“We know what takes us out of it. Our bodyminds wrest control and we try to hold that as an exquisite seed of disability knowledge to plant next time. Sometimes what closes things down is an object lesson in the everyday nature of ableism, when we can’t access the conversation about access itself. When it’s deep like this, it’s no wonder we can be pretty hard on each other. That too sends us away.” – Kevin Gotkin, 2025, Crip News V. 200

The above quote from disability activist and scholar Kevin Gotkin reflects on the struggle of sticking around in the fight for disability and accessibility advocacy. As Gotkin (2022) further reflects:

“Despite having been in various disability organizing spaces since 2012, I struggle to feel like I’ve stuck around anywhere in particular. I’ve been in groups big and small, institutional and off-the-grid, some with enormous goals, some super tactical. I’ve been in places that have been going for years and even decades” (para. 5).

Gotkin’s reflections underscore the exhausting and never-ending push to counter ableism and how it continually grinds against you. It is almost like two steps forward, one step back, and in the music scenarios I outlined above, perhaps a perpetual cycle.

But I also see ways forward. I see organizations such as Recording Artists and Music Professionals with Disabilities (RAMPD) advocating for disabled musician representation across various aspects of the music industry, including the GRAMMYs and Netflix. I see ensembles such as the Music Inclusion Ensemble, founded by Adrian Anantawan, that equally feature disabled and nondisabled musicians and incorporate time in repertoire planning for learning music via Braille. And I see musicians such as JJJJJerome Ellis requesting five hours before the performance in a venue to settle into the space for soundcheck, resisting the urge to “expedite” things in soundcheck settings. Ellis typically begins with a visual description of the space and the performer at the start of a performance. What if the performance didn’t begin with music but instead started with outlining these elements?

I dream of a world where disability in music is not othered, it is treasured. I dream of a world where disabled musicians can perform with their disability, rather than against it or overcoming it. Where can I ask for help if needed, but not feel obligated to help? And where all musicians can rest during soundcheck if they wish. I dream of a world where the assets and needs of disability culture and embodiment are not viewed as burdens but rather treasures. And treasures that are welcome to all, ultimately transforming expectations and outcomes of musical practice and performance.

BIO

Molly Joyce has been deemed one of the “most versatile, prolific and intriguing composers working under the vast new-music dome” by The Washington Post. Her work is concerned with disability as a creative source. Molly’s creative projects have been presented and commissioned by Carnegie Hall, GM Europe, TEDxMidAtlantic, SXSW:EDU, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Bang on a Can Marathon, Danspace Project, Americans for the Arts, National Sawdust, Gaudeamus Muziekweek, National Gallery of Art, and in Pitchfork, Red Bull Radio, and WNYC’s New Sounds. She is a graduate of Juilliard, Royal Conservatory in The Hague, Yale, and alumnus of the YoungArts Foundation. She holds an Advanced Certificate and Master of Arts in Disability Studies from CUNY School of Professional Studies, and is a Dean’s Doctoral Fellow at the University of Virginia in Composition and Computer Technologies. For more information: www.mollyjoyce.com

References

Bagenstos, S. R. (2003). The Americans with Disabilities Act as risk regulation. Disability Studies Quarterly, 23(1). https://dsq-sds.org/article/id/1434/

Charlton, J. I. (1998). Nothing about us without us: Disability oppression and empowerment. University of California Press.

Cusick, J. (2018, July 2). Stair worship. The Avery Review, (33). https://www.averyreview.com/issues/33/stair-worship

Ellis, J. (2021, November). The Clearing [Performance and talk]. The Poetry Project. https://jjjjjerome.com/the-clearing

Garland-Thomson, R. (2005). Disability and representation. PMLA, 120(2), 522–527. https://doi.org/10.1632/003081205X47436

Global Disability Summit. (2025). Global disability inclusion report: Accelerating disability inclusion in a diverse and changing world. https://www.globaldisabilitysummit.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/GIP03351-UNICEF-GDIR-Full-report_Proof-4.pdf

Gotkin, K. (2025, September 15). Crip News v.200: Reflecting on 200 issues, calls, and events [Newsletter]. Crip News. https://www.cripnews.com/p/crip-news-v200

Hehir, T. (2002). Eliminating ableism in education. Harvard Educational Review, 72(1), 1–32.

Herman, J. (2023–ongoing). LAX. Jerron Herman. Retrieved October 14, 2025, from https://www.jerronherman.com/lax

Hutcheon, E., & Wolbring, G. (2013). “Cripping” resilience: Contributions from disability studies to resilience theory. M/C Journal, 16(5). https://doi.org/10.5204/mcj.697

Joyce, M. (2023). Virtuosity of the self. In L. Devenish & C. Hope (Eds.), Contemporary notions of musical virtuosities. Routledge. https://www.routledge.com/Contemporary-Musical-Virtuosities/Devenish-Hope/p/book/9781032310855

Joyce, M., with contributions from Kayla Hamilton. (2023). Reimagining the vision of dance: Kayla Hamilton’s Nearly Sighted/unearthing the dark. Americas: A Hemispheric Music Journal, 31, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1353/ame.2022.a911966

Kafer, A. (2013). Feminist, queer, crip. Indiana University Press. https://iupress.org/9780253009340/feminist-queer-crip/

Kuppers, P. (2003). Disability and contemporary performance: Bodies on edge. Routledge.

Lewis, T. (n.d.). Ableism. Critical Disability Studies Collective. University of Minnesota. https://cdsc.umn.edu/cds/terms

Oliver, M. (1990). The politics of disablement. Macmillan Education.

Schalk, S. (2018). Disability, race, and teaching with joy. Smith College Faculty Publications, 27. https://scholarworks.smith.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1026\&context=eng_facpubs

Scheiber, N., & Gelles, D. (2025, March 13). How corporate America turned its back on DEI. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2025/03/13/business/corporate-america-dei-policy-shifts.html

Shannon, F. (2018–ongoing). Do you want us here or not. Finnegan Shannon. Retrieved October 14, 2025, from https://www.finneganshannon.com/do-you-want-us-here-or-not

Smilowitz, S. (2021, July 6). For true marriage equality, end the SSI marriage penalty. Georgetown Journal on Poverty Law & Policy. https://www.law.georgetown.edu/poverty-journal/blog/for-true-marriage-equality-end-the-ssi-marriage-penalty/

Young, S. (2014, June). I’m not your inspiration, thank you very much [Video]. TED Conferences. https://www.ted.com/talks/stella_young_i_m_not_your_inspiration_thank_you_very_much