The Corn Synth: Gesture and Inclusive Improvisation informed by Pauline Oliveros’s AUMI (Adaptive Use Musical Instrument)

In the Cornfield

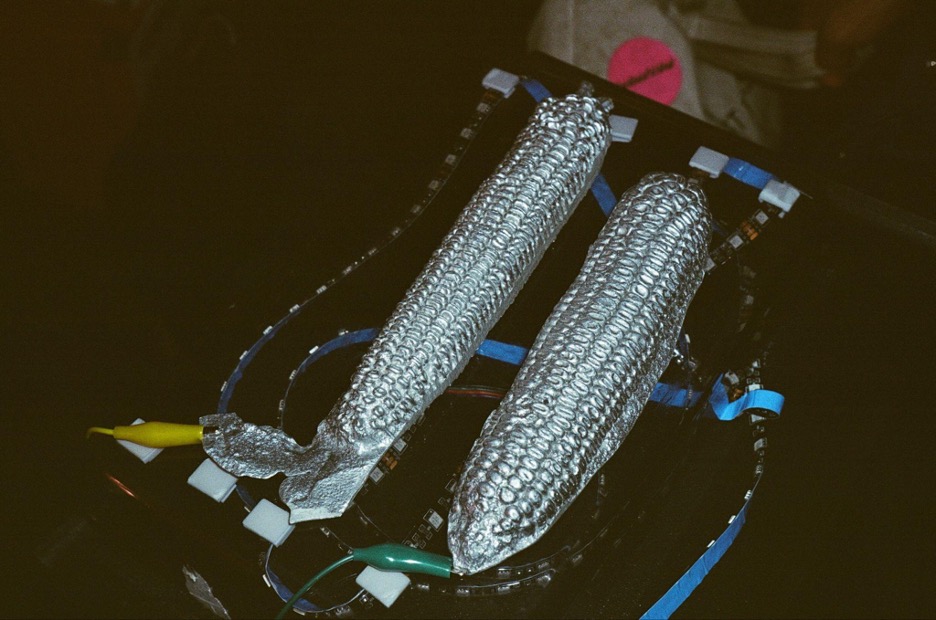

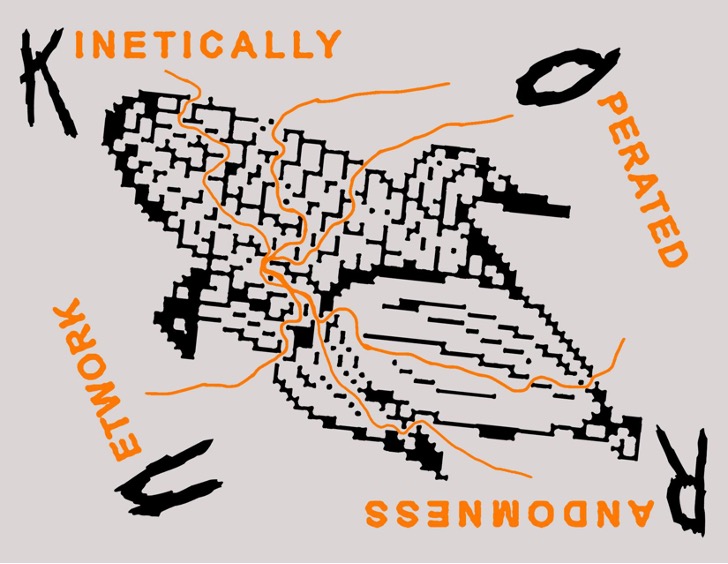

The corn synth (Kinetically Operated Randomness Network, or KORN) originated in equal parts from convenience of location and my interest in accessible instrument design. At ACRE (Artists' Cooperative Residency and Exhibitions) in Steuben, Wisconsin, I cast two aluminum corn cob sculptures, which became the physical interface for a eurorack modular synthesizer system. At ACRE I was the only sound practitioner amongst a cohort of artists working primarily in visual media, and we had the opportunity to take part in a metal pouring workshop in a nearby cornfield. The gesture of that moment, irreverent as it may have been at the time, created an instrument that transformed a ubiquitous agricultural object into a site of renewed sonic exploration. The casting process – pouring molten aluminum in an outdoor foundry surrounded by the living crop – embedded its objecthood with layers of meaning before I considered using it as a sound controller. Once “switched on,” movement and touch across the metallic corn kernels determines pitch, velocity, and duration parameters, creating what Christopher Small might recognize as "musicking,” incorporating the physical, spatial, and social dimensions of performance.1 The corn becomes not merely a controller but a sculptural presence that carries a lore and an identity of its own into each performance.

Connecting to AUMI and Universal Design

The design philosophy behind the corn synth draws directly from my collaboration with Pauline Oliveros's final project AUMI (Adaptive Use Musical Instrument) and subsequent work with the disability community through several schools and multidisciplinary arts organizations in the San Francisco Bay Area. Like AUMI, which accommodates various body types and ranges of movement, and thus may realize a broad range of musical and expressive goals, the corn synth prioritizes accessible entry points to electronic music-making, and the tactile, sculptural interface invites fun and imaginative engagement.

Through community collaboration, I have internalized principles that extend beyond “accommodations” to fundamental reimaginings of what musical instruments can be and who they can serve. In the Adaptive Instrument Ensemble (AIE), a group that ran from 2017-2021 initially for my thesis project at Mills College in Oakland, California, "musicality is recognized as an innate human capacity and basic response to the human world."2 The corn synth and the core of my philosophy operates from this premise. The direct communication of musical expression is not at all necessarily linked to formal training, and instruments should facilitate rather than gatekeep idiosyncratic musical expression.

The corn sculptures promote a kind of visual curiosity and absurdity, immediately signaling that this is not necessarily an instrument that demands reverence or expertise, though it certainly has the capacity to hold complexity and nuance. It invites play, experimentation, and hopefully some kind of uninhibited human/instrument interaction.

The conditions I seek to create in this interaction are akin to how I began working with community-centered music improvisation in ability-inclusive contexts. Between 2014 and 2017, I belonged to the late Danny “Monster” Cruz’s band Flaming Dragons of Middle Earth (FDOME)3 while working as his care assistant. The band’s credo was expansive and open, with Danny’s propulsive improvised lyrics at the fore. This project brought together many otherwise distant contingents of the western Massachusetts music scene in rock-and-roll unity. I left my job with Danny in 2015 for a full-time position at Viability, a community-based day program serving adults twenty-five to seventy-plus with developmental cognitive disabilities, many of whom lived independently. Here I programmed arts activities for our thirty participants and took them on outings. Danny’s group hosted weekly “open practice” (anyone could participate in the weekly jam) at the Brick House Community Center in Great Falls, Massachusetts. With this connection, I began facilitating weekly musical improvisation sessions with my new clients and concerts around town.

Later in 2022 in San Mateo, California, while teaching at Stanbridge Academy, (“a caring, inclusive K–12 school for students with mild to moderate learning differences and social communication challenges,”) I invited visiting CCRMA (Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics at Stanford University) research fellows Balazs Andras Ivanyi, Truls Bendik Tjemsland, and Lloyd May to co-facilitate participatory design sessions for their Collaborative Accessible Digital Musical Interface (CADMI)4 called boxsound. Ivanyi, Tjemsland, May, and I conducted user research workshops by first focusing on observing and understanding neurodiverse students before proposing creative interventions. We viewed early engagement with participants as a form of embodied listening, and learned from simply sharing space and watching how students interacted with one another before introducing new activities. This ensured that design evolved from lived behavior rather than from theoretical assumptions about accessibility.

In a workshop dynamic, the facilitator's role includes creating "an unconstrained, accessible environment" where holding space means making "it safe for others to be who they are."5 The absurd proposition of touching two aluminum ears of corn to make music has the capacity to eliminate failure as a category. This psychological safety proves crucial for inclusive collaboration and for my solo practice.

The corn synth holds space for varying degrees of complexity of interaction. A newcomer can produce interesting sounds immediately through basic touch; it is a continually deepening and evolving architecture with an established sonic identity. This scalability reflects the capacity to hold varying levels of musical engagement.

The Legacy of Mills College CCM and the San Francisco Tape Music Center

The powerful echo and artistic legacy of Mills College's Center for Contemporary Music (1967-2022) resonates in my design of the corn synth, modeling its primary voice after the Buchla 158, the original synthesizer used at the San Francisco Tape Music Center beginning in 1963. When the San Francisco Tape Music Center moved to Mills College in 1966, with Pauline Oliveros as one of three founding members (alongside Morton Subotnick and Ramon Sender), it established a model of experimental music practice rooted in community access and technological democratization. The Tape Music Center, later established as the Center for Contemporary Music at Mills College upheld its role as community center by providing access to electronic instruments and studio time for individuals in and outside the institution. The philosophy that experimental electronic music tools should be available beyond institutional gatekeeping directly informs my predominantly DIY approach to music making and community practice.

The Buchla 158 represented a particular approach to electronic instrument design that prioritized exploration and discovery over replication of existing musical paradigms (aka “west coast” synthesis). Unlike the keyboard-based synthesizers that would come to dominate commercial markets, Don Buchla's instruments used alternative interfaces: touch plates, sliders, sequencers, that encouraged users to imagine new forms of musics. By modeling the corn synth after this lineage, I position the instrument within a tradition that values accessibility through unfamiliarity. When an instrument doesn't resemble what we expect musical instruments to look like, it dispels preconceptions about how music should be made.

Leaving Mills College for UC San Diego after one academic year, Pauline Oliveros developed her Sonic Meditations, text scores focused on "enhancing listening skills and exploring new forms of collaborative social structures," intended for individuals "for whom no special skills are necessary"6 working over a long duration of time. This democratizing impulse runs through Mills CCM's history and finds expression in the corn synth. The corn sculptures require no special skills, only willingness to touch, move, and explore. The modular/Norns hybrid sampling environment currently in use with the system offers varying degrees of causal complexity, translating simple gestures into simple punctuations or rich sonic textures.

Oliveros, the social practitioner, handled community as material for composition in ways others might use pitch, rhythm, and timbre. The location of my work with AUMI in the Bay Area, in spaces touched by Oliveros's influence and surrounded by the continuing legacy of Mills CCM here (even after the institution's closure in 2022), has been formative. This project is inextricably linked with the accumulated artistic, social, and political histories that shape how we think about access, community, and experimental music practice in this region.

Modularity, Ubiquity, Accessibility

The modularity of corn as a ubiquitous agricultural monoculture in repeating sculptural form mirrors the modular synthesis paradigm, wherein discrete units combine in infinite configurations. Individual components (oscillators, filters, envelope generators, effects processors) produce often disparate sonic results depending on their signal flow. This reconfiguration is an integral part of the design, with no single "correct" way to assemble the system.

The corn synth’s modularity (the only thing static since its inception in 2021 has been the ears of corn and the Buchla 158 voice) allows me to continuously evolve the instrument's capabilities. Modules are often swapped out, signal paths reconfigured, parameters remapped, new programs used. Like the AIE, the corn synth is always a work in progress. The instrument grows and changes based on performance needs, collaborator interests, and my own developing understanding of what electronic systems and gestural instrument design can do.

The Corn Synth Demands Deep Listening

The disconnect between visual expectation (corn as food) and sonic function (corn as controller) generates a discrepancy in sound causality — a deliberate conceptual rupture of a direct correlation between what we see and what we hear. Disrupting causality between physical gesture and sonic result creates my ideal starting point for a musical performance.

Traditional acoustic instruments maintain clear causal relationships: strike a drum and you hear the impact, bow a string and you hear friction-generated vibration, blow into a horn and you hear the resonance of an air column. Some early electronic instruments mimicked these relationships: Moog synthesizers adopted piano-like interfaces to leverage existing muscle memory and performance practice. Following the “west coast” synthesis model pioneered by Don Buchla, the corn synth intentionally breaks these expectations.The sound has no "logical" relationship to the gesture that produced it. Moving a hand across the surface shifts parameters, but not in predictable ways. Random generative parameters built into the system introduces chaos, ensuring that the same gesture rarely produces identical results across multiple iterations.

Illogical causality serves multiple purposes. It levels the playing field between experienced musicians and beginners, and allows for a “beginner’s mind”. When an instrument doesn't behave "logically," technical virtuosity does not provide an expected advantage. Illogical causality foregrounds listening. When you cannot predict what sound will result from your gesture, you must listen carefully to discover what is happening. This enforced attentiveness resonates with Oliveros's Deep Listening practice, where "prolonged effects of these pieces were intended to produce heightened states of awareness or expanded consciousness."6 The corn synth demands Deep Listening.

Free Improvisation, Nonhierarchical Structures

As Derek Bailey wrote on free improvisation, the music "has no stylistic or idiomatic commitment. It has no prescribed idiomatic sound. The characteristics of freely improvised music are established only by the sonic musical identity of the person or persons playing it."7 The interface becomes a foundation for this openness, where the illogical causality of the corn disarms hierarchies of musical expertise and creates space for genuine experimentation.

Free improvisation as musical practice has historically created nonhierarchical space centered on individual embodied stylistic idiosyncrasies. This stands in contrast to Western art music traditions, where hierarchies of composer over performer, conductor over ensemble, virtuoso over amateur structure musical relationships. In free improvisation, authority disperses across all participants. When it works and the players are truly listening, each voice matters equally, each contribution shapes the collective sound.

Initially intended for solo performance, random parameters within the corn system introduce a kind of collaborator whose behaviors cannot be entirely predicted or controlled. This creates dialogue between human intention and machine response, a negotiation rather than simple gestural relationship, mirrored in other points of inspiration for the project such as Pauline Oliveros’ Expanded Instrument System (EIS) and Laetitia Sonami’s Lady’s Glove.

Corn makes for an accessible instrument, at once charming and absurd, while also a merging of my practice creating space for unrestricted musical improvisation. The gesture-sound relationship varies across the modular environment: some mappings provide direct correlation between physical action and sonic result, while others introduce chaos. This variability reflects varying degrees of direct gesture-sound relationships allowing for diverse forms of embodied expression.

Gesture in musical performance carries meaning beyond simple sound triggering. How we move our bodies, the quality of our touch, the speed and dynamics of our motions communicate intention, emotion, and identity. The corn synth attempts to create a unique approach to these factors with the idiosyncratic physicality required to play it.The tactile feedback of the cast corn, preserving the texture of individual kernels, encourages exploration through touch, inviting performers to discover how different touches (light vs. firm, quick vs. sustained) produce different results.

While the corn synth was designed primarily as a solo instrument for myself and not for disabled performers, its accessible design principles and roots in AUMI collaboration align it in this political dimension. The instrument asserts that anyone can make electronic music, that experimental sound practice belongs to anyone who is interested.

Music and disability scholar Alex Lubet suggests that performance by people with disabilities "enables music that would be impossible for a more typically abled artist"9. This reverses deficit-model thinking about disability, recognizing that different embodiments produce different musics with their own aesthetic values and expressive possibilities. The corn synth as well as AUMI’s universal design acknowledge this by making the instrument responsive to a wide range of physical interactions, ensuring that different bodies and approaches will produce different musical results.

Broad inclusivity toward approaches of music making, however new or experienced, captures the corn synth’s intended position. The instrument welcomes trained musicians who understand modular synthesis architecture and can engage with its technical complexity, while simultaneously welcomes complete beginners who might simply enjoy touching the strange corn sculptures and discovering what sounds emerge.

Public performances with the corn synth fall somewhere between demonstration, workshop, and concert. Like the AIE ensemble’s performance at Ed Roberts Campus in 2019 (a disability activism and resource center in Berkeley, CA), we quickly attracted a crowd of lunchtime onlookers and participants, some of whom happened to be carrying their own instruments and joined in. Corn synth performances often blur boundaries between performer and audience, such as recent engagements at Garden Of Memory (Summer Solstice at Chapel of the Chimes, Oakland, CA, June 2025), and at Haight Street art walk in San Francisco in August 2025 where several audience members began playing the instrument unprompted on several different instances. The visual appeal of the corn sculptures draws people in and carries a lightness and sense of invitation.

“It isn’t the AUMI software that is important, it’s what people do with it.” – Pauline Oliveros

AUMI represents among the final legacies of Pauline Oliveros's career and is a continuation of her lifetime dedication to addressing issues of nonhierarchical inclusivity, expansion of the improvising community, and sonic embodiment as therapeutic practice. The corn synth positions itself within this lineage while asserting its own instantly recognizable identity. It carries forward principles articulated by Oliveros and enmeshed in my performance practice: that shared sound and space can be available and open to a public of all abilities, open musical improvisation has the capacity to accommodate everyone, and that instruments should facilitate rather than restrict access to music making.

Through numerous community rooted collaborations over the last decade I’ve learned how flexibility is essential: no matter how carefully planned a performance or workshop is, the most meaningful moments often arise spontaneously. The corn synth thrives in these unpredictable spaces of interaction — where design adapts to human behavior rather than the reverse and listening is preeminent. By embedding observation, playfulness, and reflection into its evolution, the corn synth continues the participatory legacy of inclusive design exemplified by AUMI.

The closure of the Mills College CCM in 2022 marked the end of an era and a major loss for the arts in the Bay Area, but the principles and practices developed there continue circulating through this ever-vibrant community. It is my hope that this instrument participates in continuation, adapting ideas about accessibility, improvisation, and sonic community to new contexts, forms, and geographies.

After attending an AIE session at Mills in 2018, music therapist Sarah Morgan wrote in an email: "There was a sense of community in the group created by having a shared space and shared goal of music making. Having studied music therapy, I can see how providing this opportunity to improvise freely with adapted instruments can bring social, physical, cognitive, and emotional benefits to all group members." This observation applies to corn synth performances in promoting inclusive, valuable musical experiences for participants with multiple/varied abilities, encouraging situations where listeners become performers and become listeners again. When these roles remain fluid, boundaries stay permeable.

The “Kinetically Operated Randomness Network” at the corn synth’s core represents a particular approach to instrument design that values unpredictability, accessibility, and absurdity as productive forces in musical improvisation. By connecting this approach to lineages of experimental music practice, adaptive instrument design, and disability justice principles, the corn synth asserts that the future of electronic music can be more inclusive, more playful, more rooted in diverse communities and geographies than its past has been.

As I continue developing and sharing the corn synth in various contexts ranging from DIY gigs, formal concerts, and community workshops, the instrument remains a site of flux. The corn sculptures stay constant, but everything around them evolves: new modules and code are added to the synthesis environment, new mapping strategies are explored. New collaborators bring fresh perspectives on what this strange instrument might do. This openness to evolution and responsiveness to adaptation are an attempt to honor the legacies of Oliveros, Mills CCM, and the global communities who taught me that music belongs to everyone willing to “music” collectively.

BIO

Matt Robidoux (they/he) is a San Francisco based composer, improviser, and educator interested in sound-gesture causality and the convergence of movement and sound as it relates to free improvisation and accessibility. Their primary instrument is the “corn synth” (Kinetically Operated Randomness Network), a modular system that interprets physical input from two “ears of corn” sculptures cast in aluminum.

References

-

“To Music is to take part, in any capacity, in a musical performance, whether by performing, by listening, by rehearsing, or practicing, by providing material for performance (what is called composing), or by dancing.” Christopher Small, Musicking: the Meanings Of Performing and Listening (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2010), 9. ↩

-

Mercedes Pavlicevic and Gary Ansdell, “Between Communicative Musicality and Collaborative Musicing: A Perspective From Community Music Therapy,” Communicative Musicality: Exploring the Basis of Human Companionship, ed., Colwyn Trevarthen and Stephen Malloch (Oxford University Press, 2010), 362. ↩

-

“Flaming Dragons [of Middle Earth] play a form of super crude/sophisticated free rock ala The Godz or even a punk-primitive Arkestra but with Cruz’s stunning, oracular vocals giving them a mainline to the freak flag style of prime Captain Beefheart, Roky Erickson and Wasa Wasa-era Broughton. Cruz’s instant lyric inventions are as mind-boggling as your favourite medium while the group lurch around on staggering brokedown rhythms somewhere between early-Sabbath, Robbie Yeats of The Dead C and The Shaggs. Their material ranges from stripped-down raps to lumbering psychedelic rock, as well as free-form freakouts w/lyrics that obsess over murder, bloodshed, astral creeps and, uh, Joni Mitchell... indeed Cruz makes most ‘sound poets’ sound like children’s entertainers.” David Keenan, Volcanic Tongue, 2013. ↩

-

Ivanyi, Balazs Andras. "Participatory Design (PD) of a Collaborative Accessible Digital Musical Interface (CADMI) for Children with Autism Spectrum Condition (ASC) to Enhance Co-located Collaboration Skills." Master's thesis, Aalborg University, 2023. ↩

-

Oliveros, Pauline. Deep Listening: A Workshop Manual, 7. ↩

-

Oliveros, Pauline. Sonic Meditations (Baltimore, MD: Smith Publications, 1971). ↩↩

-

Bailey, Derek. Improvisation: Its Nature and Practice in Music (New York: Da Capo Press, 1993), 83. ↩

-

Cox, Arnie. Music and Embodied Cognition: Listening, Moving, Feeling, and Thinking (University of Indiana Press, 2016), 37. ↩

-

Lubet, Alex. Music, Disability, and Society (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2011), 41. ↩